Navigating the Minimum Wage Decision

Companies that don't raise wages for their lowest-paid workers risk becoming severely short-handed.

Employers across industries nationwide say they can't find enough workers to fill open jobs. The tight labor market has given employees more leverage on pay, and many organizations have concluded that they need to raise compensation, especially among their lowest-paid workers, to attract needed talent. In recent months, some large banks, retailers and restaurant chains increased the minimum amount they pay their employees to $15 and even $20 per hour.

That far surpasses the current federal minimum wage of $7.25 per hour, which Congress has left unchanged since 2009. In the absence of action on the federal level, several states and localities have raised their minimum wages. Currently, Washington, D.C., leads the way at $15 per hour. Several other states are following or plan to follow suit over the next few years. In some cases, these jurisdictions have also introduced periodic indexing to keep pace with inflation without additional legislative action.

Employers not obligated by law to raise minimum pay must consider the consequences of doing so. After all, pay increases are difficult to take back. And not all businesses are willing or able to pay $15 per hour. Their reluctance to increase their minimum wage is based in part on a fear of acting before it is clear whether the current upward pressure on wages is a lasting trend or a temporary trend.

That leaves some employers in a difficult position: leave wages as they are or raise them less than the current market demands, with both options risking a severe labor shortfall.

A Board-Level Concern

Raising minimum wages is "a hot topic that extends all way to the board of directors," says Craig Rowley, senior client partner with Korn Ferry Hay Advisory in Dallas. Payroll is a huge expense for employers, particularly in industries such as retail where pay can represent 30 percent of revenue. "It requires a high-level conversation to find the right solution," he says.

Employers that do raise their minimum wage often act to offset the increase in costs. For example, some companies reduce the amount of labor they need by investing in automation or having fewer people working on the sales floor during a given shift. One fashion retail chain responded to mandated minimum wage increases by hiring more people and cutting the average number of hours each employee worked, thereby reducing the number of employees eligible for benefits, according to a recent academic study.

However, employers should also consider how increasing minimum pay can be financially beneficial. Take turnover. "It costs 1.5 to 2 times salary to replace an employee, even if that employee earned minimum wage," says Amy Mosher, chief people officer at HR technology firm iSolved in Charlotte, N.C. "The longer it takes to fill a position, the more expensive it becomes."

In fact, even when raising wages a couple of dollars an hour, Mosher says, "it becomes painfully obvious that this will pay for itself very quickly." Her firm has started raising its minimum wage and plans to be at $15 per hour by early 2022. "We have already seen a reduction in turnover, which is what we hoped for," she says.

Of course, employers that raise wages too much or too soon could increase their fixed costs more than necessary. "It could take six to nine months to work this out, but there will still be pressure on wages," Rowley says.

Employers that are hoping wages return to the pre-pandemic status quo are likely to be disappointed. "The current situation represents a significant labor market shift that is causing severe and significant disruption," says John Bremen, managing director of human capital and benefits with Willis Towers Watson in Chicago. "Although the [pay] pendulum will swing back, I don't think it will swing back to pre-pandemic levels."

Finding the Right Approach

So where does this leave employers? In the current labor market, mandated wage levels are often much less important than the amount an employer needs to pay to attract talent. "Companies should not be waiting for policy changes related to minimum wage," Bremen says. "They should be doing what is right for the company."

That means determining how much they need to pay their employees in order to avoid higher-than-average turnover, staffing shortages and operational disruptions.

In fact, the minimum wage debate is just background noise for many employers that already pay premium wages. As a manufacturer based in Massachusetts, Phillips Screw Co. is dealing with a hot labor market—so much so that the state-mandated minimum wage, currently the highest in New England at $13.25 per hour, did not matter when the company decided to set its minimum wage at $16 per hour.

"There is strategic pressure to keep wages low because of price and profitability concerns," says Wes Stoskopf, the company's vice president of finance and administration in Wakefield, Mass. "We've had to move beyond that because of concerns about employee turnover and the resulting cost to quality."

While the company has seen some turnover, this churn fortunately has not occurred among the employees filling higher-level technical positions. "If we don't treat people well, they will jump," Stoskopf says. If the company is unable to attract strong enough talent to fill those positions, the result can lead to quality problems that increase costs and delay shipments. "Manufacturing is not plug-and-play; there is a significant learning curve involved," he notes.

The Value Proposition

When considering pay adjustments in response to market pressure, base pay rates should only be part of the compensation discussion, albeit a very important part. Employers must also consider the competitiveness of their entire value proposition—pay, health and retirement benefits, paid time off, flexibility, work environment, career opportunities and training, and so on.

A robust value proposition can make a difference if base pay is below that of competitors for talent. For example, an employer that pays $11 per hour and provides health care coverage may find it easier to attract workers than an employer that pays $15 per hour with no benefits.

The value proposition can also be a key element when recruiting workers who have left the workforce during the pandemic. While the availability of unemployment compensation had made it easier for some people to stay out of the labor market, an individual's personal values and situation also play a role.

"Employees have to consider the cost of child care and not having the flexibility to be there for their families," Mosher says. If companies can help a worker or job candidate better manage these competing priorities—for instance, by offering subsidized child care, flexible scheduling or other related benefits—they need to communicate that to current and potential employees loud, clear and often.

For example, Phillips Screw makes sure its employees and job candidates know it pays 75 percent of the cost of employee health coverage. Additionally, when the company was able to hire several employees from a distressed manufacturer with an unhappy workforce, it emphasized both its higher wages and its success at addressing employee safety concerns during the COVID-19 pandemic. Communicating those benefits opened the eyes of employees to what they are getting when they join the company and what they are leaving behind if they depart, Stoskopf says.

This is also a good time for employers to take a big-picture look at their entire approach to employee compensation for all employees or targeted groups of workers. If an organization has traditionally positioned pay at the 60th percentile for workers with critical skills but is having trouble filling openings, the market for talent may be too constrained for that positioning to continue being effective. By offering higher pay, the employer may be able to gain access to more and better talent, Bremen suggests.

This is especially true given the labeling of "essential workers" during the pandemic. If these essential workers now believe they are necessary to keep the company's operations running, it becomes that much harder for employers to argue that current pay levels are appropriate. "Essential workers are still essential after the pandemic," Bremen says. Pay positioning should become a recurring discussion as the definition of critical skills and essential workers evolves over time.

Sending a Signal

Some employers that have raised pay above the mandated minimum wage have acted for their own strategic reasons. As a rapidly growing company, Delavan, Wis.-based Geneva Supply Inc. increased its minimum wage for new hires from $12 to $15 per hour to improve its talent pipeline and support continued growth, while also defining itself as a top employer.

Since 2018, Geneva Supply has needed employees—and lots of them. Roughly doubling its workforce each year, the company now has 175 full-time workers in three locations and is planning to open three more facilities in the U.S. and one in Europe in the near future. Thanks to the demand for its pack-and-ship warehouses, which have been indispensable to manufacturers shipping directly to consumers during the COVID-19 pandemic, the company realized its planned growth trajectory in 18 months instead of the expected three to five years.

The company has not lost any employees to competitors, including an Amazon fulfillment center that pays $15 per hour within 45 minutes of one of Geneva Supply's locations. "We were able to manage that through our culture, available overtime and the benefits package," says company CEO Jeff Peterson.

However, company leaders also recognized that raising minimum pay would help improve employees' standard of living. By playing a role in helping employees improve their lives, possibly find a better place to live and not stress as much about their financial situation, the company knew it would be able to build stronger ties to its employees.

The pay increase was three years in the making. After working through the details of the minimum wage hike with corresponding changes to company budgets, "we just had to find the right time to flip the switch," Peterson says. That time came on May 1, when the company rolled out the increase and also eliminated the waiting period for employee benefits eligibility so new employees have access to the full benefits package on their first day of work.

Peterson notes that the amount an employer pays its people sends a powerful message. "This is not just about individuals making more money," he says. "This shows who we are as a company, what we stand for, and how we can positively impact employees and their families and their entire communities."

Joanne Sammer is a New Jersey-based business and freelance writer.

Explore Further

SHRM provides advice and resources to help advice and resources for business leaders to make strategic decisions about employee pay.

Biden Raises Federal Contractors' Federal Wages, Putting Pressure on the Private Sector

A wage of at least $15 per hour must be paid for work done by federal contractors, under an executive order signed by President Joe Biden.

Will a $15 Minimum Wage Hurt Small Businesses?

Small businesses have been especially hard hit during the COVID-19 pandemic. That's why some believe this is an inopportune time to pursue raising the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour. Locality-based wages may be one solution.

Complying with Minimum Wage Laws in 2021

Many state and local minimum wage rates have been steadily rising in recent years, and some have reached or surpassed $15 an hour. That presents challenges for employers with multistate operations.

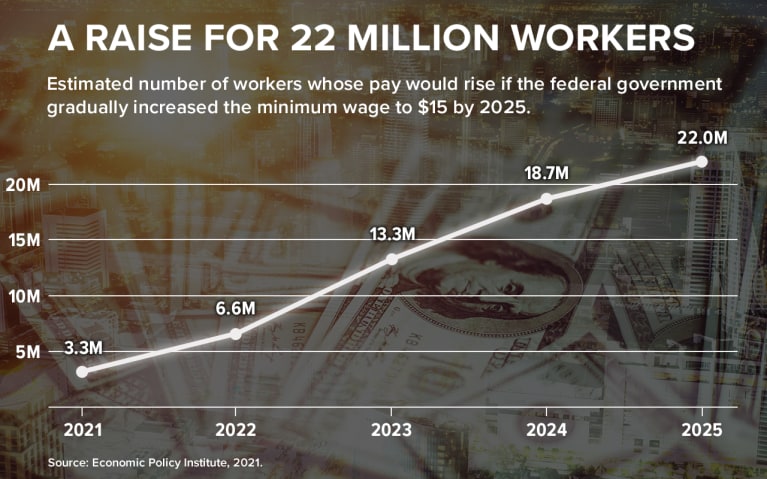

CBO Analysis: $15 Minimum Wage Would Boost Incomes, Trigger Job Cuts

Raising the federal minimum wage to $15 per hour would increase pay for 27 million workers but also lead to more than 1 million job losses, according to Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projections.

SHRM Interactive Multistate Law Comparison Tool

Build a side-by-side chart to compare state labor laws, including minimum wage requirements.