Is It Time to Talk About Race and Religion at Work?

Some corporate leaders are encouraging employees to engage in sensitive conversations to build more-inclusive workplaces.

Introduction

Like many black parents, Rah Thomas goes to work each day worried about whether his 13-year-old son is safe. The highly publicized police shootings of several unarmed black men over the past two years weigh heavily on his mind.

Although he has taught his son how to respond if stopped by police, he recognizes that something could go wrong.

“These things are going on in society, and then you have to brush it off and go to work,” says Thomas, 36, who is a managing director at Accenture’s Operations business in the New York City area. Unlike his white colleagues, he says, “I don’t have the luxury of just shutting it off.”

Until recently, Thomas never felt he could share his concerns with colleagues. But now Accenture’s leaders are encouraging employees to discuss sensitive topics such as racial or religious discrimination—subjects once considered taboo in the workplace.

Julie Sweet, group CEO of Accenture North America, and Ellyn Shook, chief leadership and human resources officer, kicked off the discussions with a town hall-style webcast called Building Bridges in 2016. That spawned smaller sessions in various regions, including one in New York that Thomas facilitated.

“It was definitely refreshing to see at the highest level the senior leadership sponsoring a conversation about this,” Thomas says. “Once it happened, I felt empowered.”

With Americans more divided than ever on racial and religious issues, a growing number of corporate leaders are recognizing that societal tension and discrimination can have a significant negative impact on employees when they’re at work.

Accenture is one of more than 300 companies whose CEOs are coming together to create ways for workers to feel more comfortable sharing their personal experiences—and to gain a greater awareness of others’ perspectives. By encouraging employees to have difficult conversations, they hope to build trust and encourage compassion so that all workers feel more included. The companies are sharing their ideas and practices through the website CEOAction.com.

“We truly have an unwavering belief that our diversity makes us smarter and more innovative,” Shook says. “So, taking a very broad view of diversity is a very important business issue for us.”

U.S. corporate leaders have recognized for years now that changing demographics make it necessary to expand their markets. By 2044, more than half of Americans are projected to belong to a group other than non-Hispanic whites, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

“What we’ve seen in our company is that when we create an environment where all people feel like they belong, you truly start to see people flourish and performance both at the individual and the organization level also flourish,” Shook says.

Holding Back

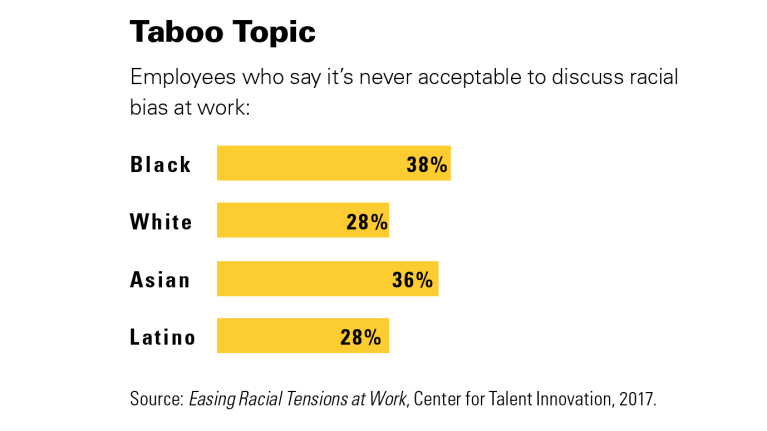

Thomas’ earlier belief that he couldn’t share his true feelings at work is hardly unique. About 78 percent of black business professionals say they’ve personally experienced discrimination outside of work or fear that they or their loved ones will. Yet 2 out of 3 surveyed report being uncomfortable discussing race relations at work—and 4 out of 10 black employees say it is never acceptable at their company to speak about experiences of racial bias, according to a report by the Center for Talent Innovation released in June 2017.

That silence can be devastating. Those black professionals who can’t share their life experiences at work are more likely to feel isolated—and are almost three times more likely than those in other racial and ethnic groups to intend to leave their employer within one year, says Laura Sherbin, co-president at the New York City-based think tank focused on global talent strategies.

“You certainly don’t forget about the safety and the security of your family during the hours of 9 to 5,” Sherbin says.

In addition, avoiding the issue creates another layer of difference between the employee and his or her colleagues. “If the emotionally painful incident is top of mind for you, and the CEO doesn’t so much as mention it, … it means they don’t value you, your family and what is critically important to you,” Sherbin says.

‘Diversity is simply having representation. Inclusion is when people get invited to be at the table. And belonging … is the emotional connection that people are feeling to each other and to the organization.’

‘Diversity is simply having representation. Inclusion is when people get invited to be at the table. And belonging … is the emotional connection that people are feeling to each other and to the organization.’

—Ellyn Shook, Accenture

Even if someone else raises the issue of racial discrimination, many black employees don’t feel free to openly express themselves. “They still feel they have to edit themselves,” she says. “If they’re editing this, they are also editing other aspects of themselves, including their contributions to work.”

Studies have shown that companies with greater racial, ethnic and gender diversity perform better financially. But the business benefits of diversity are lost if employees don’t feel comfortable speaking up.

“If they can’t bring their whole selves to work, and they can’t bring their ideas to work, the exact value-add that you hired these individuals for is lost,” Sherbin says. “Because if all they’re doing is editing themselves to become reflections of past leaders that have been successful in your company, it will not drive your company into the future.”

To move forward, what you need “is innovation, new ideas, people not afraid to fail, to take a risk,” she says.

Diversity Without Inclusion

While many organizations have what they call “diversity and inclusion” programs, having a diverse staff doesn’t necessarily equate to inclusion. And, studies show that diversity without inclusion can invite resentment.

“Diversity is simply having representation,” Shook says. “Inclusion is when people get invited to be at the table. And belonging, which is the third piece of our I&D [inclusion and diversity] efforts, is the emotional connection that people are feeling to each other and to the organization. That is where we see the next frontier,” she says. “When people feel like they belong, what we’re seeing is that they can more fully participate in their work activities.”

Earlier this year, Accenture held a series of workshops exploring how its 411,000 employees, just over half of whom are ethnically diverse, felt about the concept of belonging. The workers and their ideas were captured in a video, “Inclusion Starts With I,” which has been made available on YouTube so that other organizations can use it to start the tough conversations needed to move toward a more inclusive workforce.

The video was shown to 750 Accenture managing directors at an annual training in June where they were asked to commit to driving change. Afterward, the room was silent as they absorbed the emotional message and one by one they stood to show their support.

“What started as a simple moment has really turned into a movement,” within and outside the organization, Shook says, as the video’s popularity has soared.

After the deadly white nationalist rally in Charlottesville, Va., in August, employees at Accenture’s New York City office invited five leaders of various faiths to a Building Bridges discussion in which workers sought to understand differences in their religions. Afterward, the employees went to a kosher restaurant for a Shabbat dinner.

A Segregated Nation

Is the workplace an appropriate place for such discussions? In fact, Sherbin argues, it’s the best place—because work is one of the most desegregated environments in American society.

In neighborhoods, at social events, even at places of worship, people rarely interact with individuals outside of their own racial or ethnic groups.

“For many individuals, the workplace is actually their first opportunity to communicate with somebody who speaks a different first language than they do, who grew up with a different socioeconomic background, who is a different race or ethnicity,” she says. “By creating positive environments around differences in the workplace, we really do believe that that will then spill over to our society and we will create positive environments around it in our society.”

Raising Awareness

After racially charged shootings in Baton Rouge, La., Minnesota and Dallas heightened societal tensions in 2016, Tim Ryan, the then-new U.S. chairman at accounting giant PwC, convened companywide “ColorBrave” conversations in which employees were encouraged to share their life experiences.

“We found that a lot of people wanted to come together to connect,” says Mike Fenlon, chief people officer at the accounting giant based in New York City. “For everyone, it was the basis for learning and insights. It wasn’t for political debate.”

Fenlon, who is white, recalls an eye-opening moment when a black male partner shared how differently he is treated when he wears a suit and tie at work compared to a T-shirt on the weekend.

"It was a powerful moment because this is someone I know and someone I care about,” Fenlon says, and it didn’t occur to him that someone might view his colleague as a threat simply because of race.

The conversations were intentionally informal. The HR team provided guidance at the large forums, including an introductory video that modeled helpful conversations, but there wasn’t a lot of structure.

It helps to acknowledge at the outset the trepidation that everyone is feeling and to stress the need to be forgiving. While the words might not come out right, emphasize that they come from a place of caring, Fenlon says.

‘When you start to share personal experiences with people, you start to connect with them.’

‘When you start to share personal experiences with people, you start to connect with them.’

—Rah Thomas, Accenture

While such discussions can be uncomfortable, the openness helps build the relationships needed for strong teams.

“We know from research that one factor that influences the quality of any team is psychological safety. It’s trust, an environment where people can be open and have candid dialogue,” he says.

To help others raise awareness, PwC is sharing its “Blind Spots” training videos and discussion guides on unconscious bias.

Earlier this year, The Hershey Co. also held a series of discussions with employees about the bias, marginalization and discrimination that some are experiencing.

“Now more than ever, we want to make sure every individual throughout our company feels encouraged and included,” says Alicia “AJ” Petross, senior director, global culture, diversity and inclusion and engagement, at Hershey, headquartered in central Pennsylvania.

Representatives of Hershey’s eight business resource groups met with about 100 senior leaders to discuss how the group members were reacting to events in the U.S. The HR team developed a short set of talking points and questions for leaders to use as conversation starters with their team members.

When defense contractor Raytheon Co. began a major push two years ago to hire more minority employees and improve their ability to advance within the company, it started by training its managers.

"We made a conscious decision to create a culture here where everyone feels welcome and can bring their whole selves to work each day," says Randa Newsome, Raytheon's chief human resources officer. "For us, it's critical to be able to attract and retain the most talented people for our company."

Since 2015, 95 percent of 12,000 Raytheon leaders globally have completed required diversity and inclusion training. Last year, the focus was on unconscious bias. This year, it's inclusive leadership. The HR team wants leaders to be well-prepared.

"You don't want to have people who are well-intended and mean to do the right thing, but stumble over it," she says, adding that the training helps leaders overcome their fear of making a mistake.

Break the SilenceIn its report Easing Racial Tensions at Work, the Center for Talent Innovation recommends the following ways for employers to start the conversation on race: Acknowledge racial tension. The CEO can send a message to employees that racial justice matters. Public condemnations of racial violence, like the ones several corporate leaders gave in response to the violence in Charlottesville, Va., last summer, is another way to show concern. Create the right setting. Some individuals may be more comfortable in small groups or one-on-one conversations, while others might prefer a town hall with a senior leader. Consider bringing in a diversity and inclusion specialist to facilitate if your staff isn’t trained to do so. Set ground rules to ensure that participants listen, try to understand each other and show respect. Provide education and resources. People often fear they will say the wrong thing. Offer videos and articles that explain why some phrases are offensive. Distribute tip sheets to correct common slights or stigmas about certain identity groups. Train managers to be inclusive. Invite guest speakers, and broaden your reach by inviting community members. Involve the company’s employee resource groups (ERGs). Collect ERG members’ advice in developing guidelines for any larger-scale program. Black professionals tend to feel more comfortable talking about race during an ERG meeting, even if other racial or ethnic groups are invited to participate, the center’s survey found. Even so, realize that not everyone will want to share, cautions Rah Thomas, a managing director in Accenture’s Operations business who facilitated a discussion on race at the company’s New York City location. “You can’t force someone to come out of their shell,” he says. However, when senior leaders show that they too are vulnerable, it goes a long way to creating a safe environment. “The best way to solve a problem is to confront it, to admit it and to talk through it,” he says. |

Mutual Understanding

In the group discussions at Accenture, Thomas remembers vividly the moment he heard a Muslim employee speak about being pulled out of an airport line for further scrutiny when non-Muslim colleagues were waved through the security gate. He could relate.

“I feel it as a black person with dreadlocks in corporate America,” says Thomas, whose lengthy hair reflects his West African culture.

In the discussion, white colleagues asked about the Black Lives Matter movement. “They didn’t know that ‘All Lives Matter’ might be offensive,” he says. It’s like criticizing those who support people with breast cancer for not focusing on people with other cancers—their advocacy “doesn’t mean that other cancers are OK,” he recalls explaining.

He believes such open conversations have brought about a culture shift at Accenture.

“I’ve seen an enormous growth in people participating and getting involved in activities inside the office,” he says. “When you start to share personal experiences with people, you start to connect with them.”

And while encouraging sensitive discussions can make some people uncomfortable, “the greater risk is to do nothing,” says Ashlee Carlisle, a member of the African-American business resource group at The Hershey Co. “Understand that every conversation is giving someone the courage and power to do what’s right.”

Avoiding Communication TrapsWhen diversity consultant Maura Cullen mentions the following common “dumb things people say” in her workshops, there’s an audible groan from people of color because they’ve heard the comments so often: “Some of my best friends are …” “I don’t think of you as …” “I don’t see color. I’m colorblind.” While the statements may be intended as unifiers, they often create a larger divide. Ironically, “people don’t typically say they don’t notice color until they notice color,” Cullen says. “It’s like me saying to a man, ‘I don’t notice that you’re a man.’ They would look at me like I have two heads. The problem is not noticing the difference. It’s what we do once we notice that can be the game changer.” She offers the following tips for avoiding communication traps and de-escalating tense conversations:

|

Dori Meinert is senior writer/editor of HR Magazine.

Illustration by Brian Stauffer for HR Magazine.

Was this article useful? SHRM offers thousands of tools, templates and other exclusive member benefits, including compliance updates, sample policies, HR expert advice, education discounts, a growing online member community and much more. Join/Renew Now and let SHRM help you work smarter.