New Tactic Emerges to Control Rx Spending

More employers are adopting co-pay accumulator programs in a bid to discourage employees from buying overly expensive prescription drugs.

More than a decade ago, viewers watched with a mix of fascination and confusion as news programs showed senior citizens taking buses en masse from the U.S. to Canada so they could stock up on medicines that were becoming unaffordable back home.

Now, as prices have continued to rise, a growing number of U.S. consumers can relate, and their angst over the ability to pay for prescription drugs has become a focus of heated national debate.

Consider a few examples: Between 2002 and 2013, the typical price for a milliliter of insulin climbed 198 percent, from $4.34 to $12.92. List prices for older multiple sclerosis medicines increased between 2014 and 2019, even as newer treatments became available. For example, the cost of Avonex rose to $90,035 from $59,085 per year, while Tysabri climbed to $83,152 from $60,827. The annual wholesale cost for Humira, an antiinflammatory drug dispensed via injectable pen, rose to $67,253 this year from $17,160 in 2007.

These are not isolated instances. Overall, U.S. spending on prescription drugs totaled $333 billion in 2017, up from $236 billion in 2007, according to national health expenditure data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Fourteen percent of those who have health insurance coverage through their employer said they had difficulty affording their medicines last year, a Kaiser Family Foundation poll found. And the cumulative effect is placing a growing burden on employers, too.

The cost of prescription drug benefits per organization (among those with 500 or more employees) is expected to reach 6.9 percent of the price of employee health insurance plans this year, up from 6.5 percent in 2018, according to Mercer, a benefits and management consulting firm. Meanwhile, retail pharmacy drugs amounted to 19 percent of employee insurance benefits last year, even when factoring in rebates from drug manufacturers, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

The most popular coping mechanism among employers has been to use a multitiered formulary, an approach devised by pharmacy benefit managers to shift some pharmaceutical costs to employees. This tactic also involves the use of techniques such as requiring prior authorization for some medications and step therapy—seeing if less-expensive drugs work before allowing payment for more-expensive drugs.

For the most part, these tactics have been successful, despite some employee resentment over the persistent hurdles when purchasing prescription drugs. In general, 68 percent of those with employer insurance gave their health plan an excellent or good rating, the Kaiser Family Foundation poll found.

But in an era of rising prices, new cost-control strategies are needed. One cost-saving tactic is the co-pay accumulator. This type of program is fairly new and growing in popularity, even as some critics question how much savings it really provides to employers.

Companies Explore Co-pay Accumulator Programs

In recent years, high-profile corporations such as Walmart, PepsiCo and Home Depot have adopted co-pay accumulators, and the trend is growing.

Co-Pay Cards

For more than a decade, drug makers have been offering co-pay cards to consumers who have private health insurance. The cards have become popular, and for good reason. They help employees obtain medicines at a lower cost and remove access barriers that may prevent adherence to treatment. The real appeal for anyone who gets a card is that the amount provided by the drug maker counts toward deductibles and out-of-pocket costs. By the time a card’s limit is reached, most workers have met their out-of-pocket maximum.

In a bid to push back against the drug companies, pharmacy benefit managers recently began offering the co-pay accumulator. Simply put, co-pay accumulator programs don’t count the value of co-pay assistance cards toward patient deductibles. The goal is to discourage the use of expensive medicines when cheaper or generic (and equally effective) options or treatments are available. The use of higher-priced prescription drugs increases overall health care costs for both employers and their employees.

Co-pay accumulators are “a way of getting employees to follow the formulary, and they’re targeting employees who hope to have lower health expenses, especially those who regularly need more expensive medicines,” says Susan Raiola, president of Real Endpoints, an advisory and analytics firm that tracks reimbursement issues. “And it’s a way for the company to keep its health care costs down.”

Here’s an example of how an accumulator program might work: Let’s say an employee named Joe takes a brand-name medicine that costs $20,000 a year, and, per his employer’s plan, he’s responsible for $5,000 in out-of-pocket costs. Without a co-pay card, he must cover all $5,000. But with, say, a $3,000 co-pay card, he must pay only $2,000 in out-of-pocket costs. If his employer uses an accumulator, however, Joe must still cover the entire out-of-pocket costs of $5,000 once his card is used up.

“The impetus behind our accumulator program were requests, even demands, from our clients, [the employers],” says Meghan Pasicznyk, senior director for specialty market development at Express Scripts, a pharmacy benefit manager and a unit of health insurer Cigna. “They wanted to know, ‘ Can we shut off the co-pay cards?’ ”

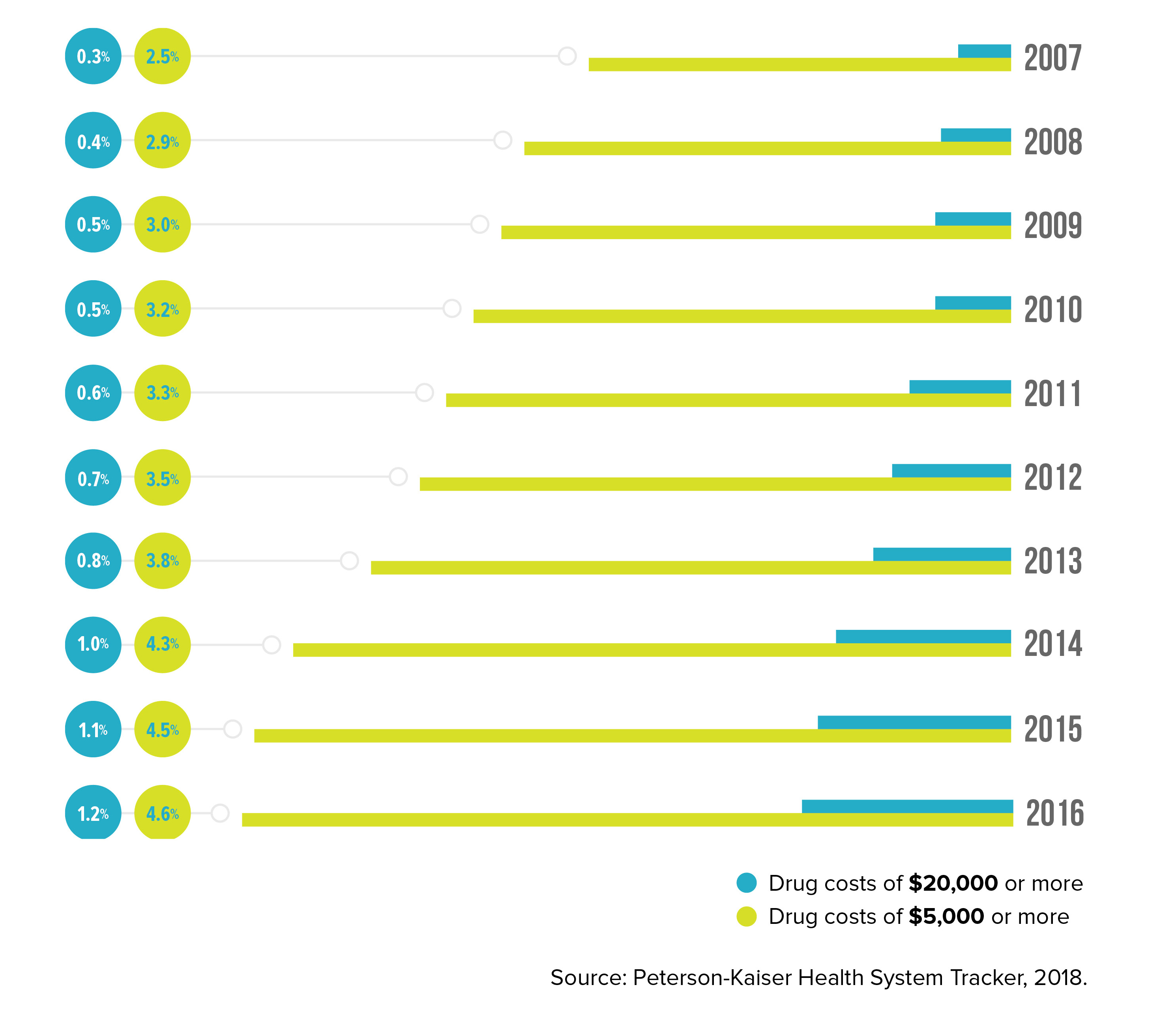

Higher Drug Bills Hit More Employees

The share of people with employer coverage who have high annual drug spending has increased in recent years.

Growing Momentum

Accumulator programs are relatively new, so there’s no reliable data yet indicating how much they may be saving employers. But the practice is gaining traction anyway.

Last year, 26 percent of corporate America had adopted an accumulator, while 3 percent said they planned to this year, and another 21 percent are considering making the move over the next couple of years, according to a survey of employers by the National Business Group on Health, a nonprofit coalition of businesses. Notably, such high-profile corporations as Walmart, PepsiCo and Home Depot have recently adopted accumulators, although none of the companies would discuss their experiences for this article.

Accumulator programs are particularly attractive because they offer organizations the possibility of holding down spending on so-called specialty medicines. These are generally higher-priced biologic drugs that are used to treat chronic, complex conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis and cancer. Humira is an example. Cancer medications, in particular, are of special concern, because many newly approved drugs are being introduced at increasingly higher prices.

“During the last few years, we’re seeing for the first time that what companies spend on specialty drugs is around 50 percent of their total pharmacy spending, yet these are medicines for conditions that only affect less than 2 percent of their employees or dependents,” says Brian Marcotte, chief executive at the National Business Group on Health.

Some Caveats

While accumulator programs may be attractive to employers, there are some caveats.

For one, workers can find these programs financially painful and surprising. Remember, once a co-pay card is used up―which typically occurs in the third or fourth month of the year for expensive drugs―and the accumulator takes hold, the employee must shoulder the full amount of the deductible.

“Take the example of someone who had a [deductible] of $1,000, but then their card is used up and they’re suddenly [having to use] their own dollars,” says AJ Ally, a pharmacy management consultant at Milliman, a global consulting and actuarial firm. “Now they get sticker shock. And they’re unhappy.”

This is especially true for employees who chose high-deductible health insurance plans, because they may be bearing a larger portion of prescription drug costs than they expected. As is, a growing number of workers are expressing dissatisfaction with high-deductible plans. Half of employees surveyed complained that their insurance coverage has worsened in the past five years, the Kaiser poll found.

Generally, organizations have nothing to gain by making their workers anxious or resentful about their finances. And there’s also the possibility of unintended consequences of high drug costs: Squeezed by medication prices, employees might choose to not fill a prescription. This lack of adherence could cause a costly downward spiral if their health suffers.

One way to cushion the blow is to forecast the effect on workers before proceeding and to educate employees, so the result is fully understood. Another option, Raiola says, is to structure an accumulator that would be spread out over a full year so that the sticker shock doesn’t emerge all at once.

Policy Issues

Concerns about co-pay accumulators have heightened as their profile has increased. Last year, a few dozen groups representing patients and providers asked state insurance commissioners to investigate the growing use of accumulators. Among those groups were the American College of Rheumatology, the National Viral Hepatitis Roundtable, the AIDS Institute, the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Patient Access Network Foundation and the National Organization for Rare Disorders. One concern is that insurance plans are using accumulators and giving little or no notification to beneficiaries, which may mislead them about their coverage.

A few states have reacted. Earlier this year, Virginia and West Virginia adopted laws that preclude individual- and small-market plans from using accumulators. Other states are considering similar legislation. In Arizona, meanwhile, a new law offers a compromise: Patients can use co-pay cards if a prescribed medication’s generic alternative isn’t available or if a medicine is obtained after the patient has undergone prior authorization to receive it.

“The end result was a compromise in which everyone made some changes we believe patients can live with and that’s not a blanket prohibition of co-pay accumulator programs at all,” says Nancy Barto, an Arizona state senator who sponsored the legislation. “It also still allows insurers the same coverage flexibility they use now to control costs. The [co-pay accumulator] programs can be discriminatory against the high-cost patient who can only afford their medications with assistance, who are then forced to either go without their lifesaving medication or go broke” paying their deductibles and insurance premiums.

Also this year, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services issued a regulation prohibiting the use of accumulator programs for brand-name drugs when an equivalent generic is not available.

Another issue is whether employers are treating all workers equally. Companies that fail to do so could find they have violated the law, according to Cheryl Larson, chief executive officer of the Midwest Business Group on Health, a nonprofit employer coalition.

Employers have a fiduciary responsibility to ensure that beneficiaries are treated equitably. “This is a big deal,” Larson says. When a co-pay card is used, she says, “some employees―who may not have a disease―get a cost advantage, and that’s not equal. So employers need to be guided carefully on this issue. A lot of smaller to midsize, self-insured employers may not be as knowledgeable.”

Costly Ailments

Percentage of people with large-employer coverage who had annual drug spending in excess of $5,000, listed by disease, in 2016.

Countermoves

Stung by the growing use of accumulator programs, the pharmaceutical industry is striking back in a couple of ways.

To maintain sales of key products and market share, more drug makers have been adding money to their co-pay cards, according to Richard Evans of Sector & Sovereign Research, which tracks pharmaceutical pricing. (This tactic, though, has hurt their net prices on brand-name drugs, which fell 4.1 percent in the first quarter of this year, partly due to the growing use of accumulators.)

Several big drug makers that sell specialty medicines support a nonprofit group called Aimed Alliance that, last fall, issued a report to dissuade employers from adopting accumulators. The group claimed organizations using accumulators may be violating the Affordable Care Act, specifically its cost-sharing requirements and anti-discrimination provisions, as well as consumer protection laws.

And some benefits experts agree that organizations should be wary of accumulators. That’s because these programs may not offer a tremendous benefit for employers, especially when considering the ongoing fallout, one expert cautions.

“Accumulators are a very clever way to counter co-pay cards, but there’s really not a lot of value to the employer” in the end, says Randy Vogenberg, a principal at the Institute for Integrated Healthcare, a consulting and research firm that specializes in health care plan benefit designs.

As Vogenberg sees it, the dollars saved are not always going to be significant. As an example, he points to a $100,000 drug regimen for which the employee ends up paying a $5,000 deductible after exhausting a co-pay card, thanks to the employer’s use of an accumulator. “When all is said and done, the employer will still pay 80 to 90 percent of the bill,” he says, “but, meanwhile, they’re risking ill will and maybe fiduciary issues.”

Ed Silverman, a journalist who runs the Pharmalot Blog, has covered the pharmaceutical industry for more than two decades.