Helping Displaced Workers Get a Fresh Start

Outskilling—company-sponsored training that can help employees find another job, or a new career, with a new organization—could reduce the pain of layoffs.

There’s upskilling and reskilling. And there’s outplacement. Now comes outskilling. It’s a term some people are using to describe company-sponsored training programs that help employees find another job, or even another career, with another employer. Will it catch on? Only if it’s treated as part of a larger, proactive workforce transformation strategy, observers say.

But with unemployment at levels not seen since the Great Depression, many companies aren’t necessarily paying attention to the subtleties of the best ways to let workers go. They’re more concerned with survival than with strategy.

Christy Harris

While few organizations have outskilling programs, the concept could gain momentum as businesses act to counterbalance the negative impact of layoffs. The programs also demonstrate a company’s social commitment to its employees and local communities.

In the long term, experts say, the following factors could help drive an outskilling trend:

- A desire to counteract the negative impacts of layoffs. Layoffs are bad news not only for workers, but also for corporate brands. In addition to causing reputational damage, layoffs can have ripple effects, hurting morale among remaining employees and making it harder to recruit top talent in the future.

- A need to ease the transition to widescale automation. As companies embrace automation and artificial intelligence (AI), they recognize that displaced employees need help transitioning to new jobs.

- An interest in embracing a new social compact. In the wake of the Business Roundtable’s 2019 declaration that corporate responsibility should extend beyond the sole interest of shareholders, outskilling programs demonstrate that a company is taking more responsibility for the welfare of its employees.

The coronavirus pandemic changes none of these considerations, says Hamoon Ekhtiari, CEO of FutureFit AI, a company that uses technology to help organizations match people with the right skills and jobs. Before the pandemic, many CEOs were “signing off on real 24- to 35-month automation business cases, so there was [already] a workforce transition question they needed to address,” he says. CHROs were already talking about how to “reimagine” the layoff experience. When COVID-19 hit, “suddenly it got very real.”

In fact, the public health crisis may speed up the move to automation and resulting layoffs, especially in environments with close person-to-person contact. Leaders in companies that operate under those conditions “are actually doubling down on their automation agenda,” Ekhtiari says.

Developing Capabilities

As the term “outskilling” has emerged among workplace learning professionals and in media reports over the last year or two, programs at two Fortune 500 companies are often cited as its poster children:

- Amazon’s Career Choice includes help for hourly workers to prepare for jobs outside the company.

- McDonald’s Archways to Opportunity helps employees further their education and move into a career within the company or elsewhere.

Notably, neither organization uses the term “outskilling” to describe their offerings.

In fact, the programs simply use education funding in a new way, Ekhtiari says. “They’re great programs, but if you peek under the hood, they’re primarily education benefit programs,” he explains. Specifically, they use the $5,250-per-year tuition reimbursement many organizations already offer employees. (Under the U.S. tax code, employers are allowed to deduct that amount annually per employee as a benefit expense, and employees pay no tax on it.)

To be effective, outskilling should be part of a broader workforce transformation strategy, says Jeff Schwartz, a principal with Deloitte Consulting and the U.S. leader of its Future of Work practice. Companies like Amazon and McDonald’s are thinking about “not just skilling programs, but capability development programs,” he explains. “They’re beginning to look at this tripartite approach of upskill, reskill and outskill.”

Amazon’s Career Choice program, for example, helps employees think about three possible paths: They can upskill to build a career within their current division; they can seek new opportunities in other divisions of Amazon through reskilling; and, “if you can’t further your career at Amazon, [the company will] help you further your career at another company in your community,” Schwartz says.

Amazon’s leaders “recognize that the more opportunity they can create for their people—even if it’s outside the company—the more loyal people will be,” he says. And because of the training the business offers, he adds, those employees are staying at Amazon longer. “For many companies, that additional six months to two years in which an employee stays with the company while getting training is very valuable.”

PwC report

Allstate is considering such a strategy, although it doesn’t use the “skilling” terminology either. “We want employees to be employable—have the relevant skills—whether it’s here or someplace else,” says Christy Harris, senior vice president at the insurance company.

Allstate recently started to think more specifically about the “someplace else” part. Previously, if the company knew it would need fewer employees in a specific type of job, it tried to give those workers long-range notice (one year, for example) and offer career/skills development or training to help them move to another job at Allstate, if possible. Now, the company is considering more-targeted ways to help workers find employment elsewhere, perhaps by helping them get certified in a trade or, if the person is nearing retirement, transitioning to a job in community service or at a nonprofit, Harris says.

Barriers to Adoption

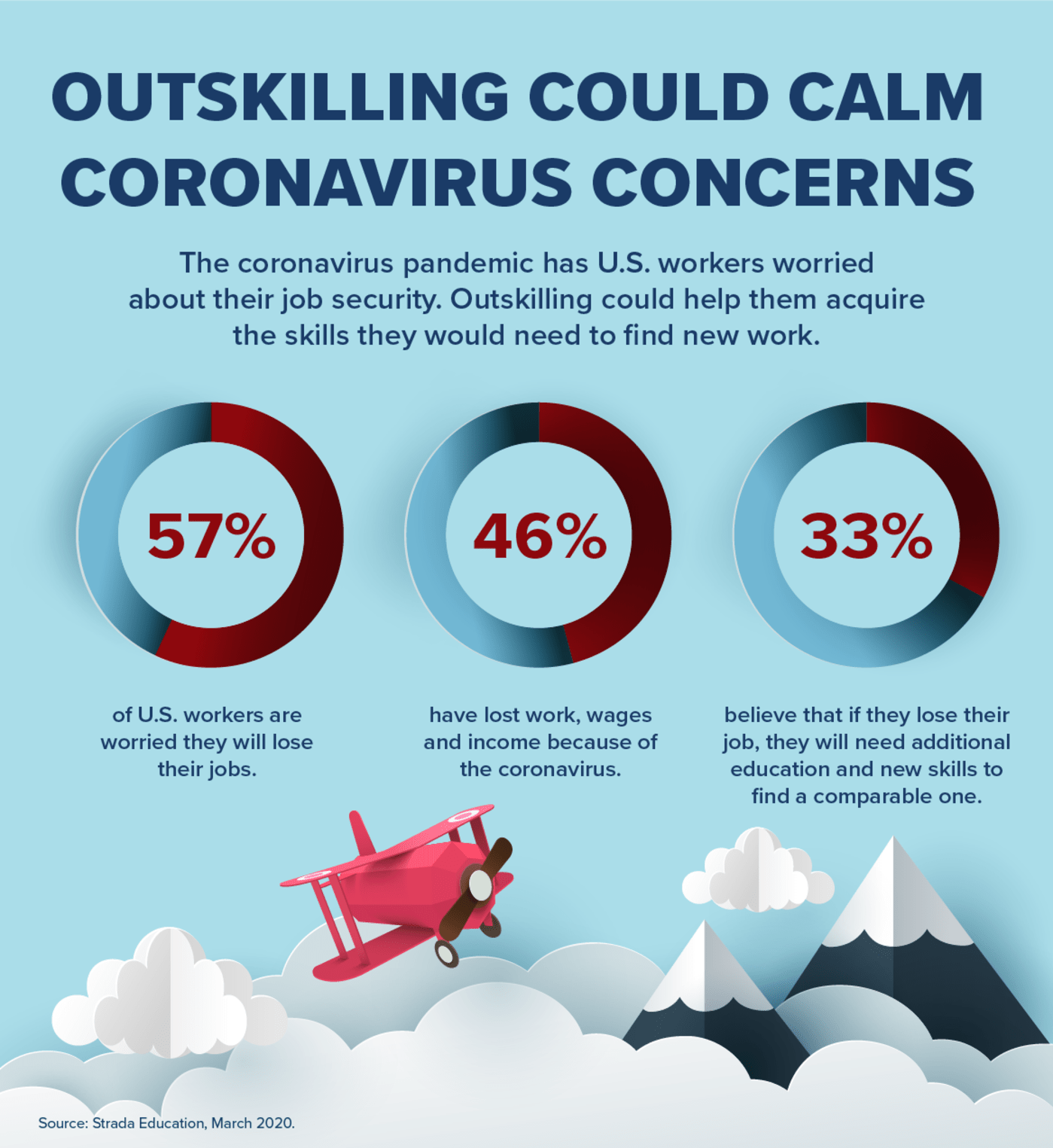

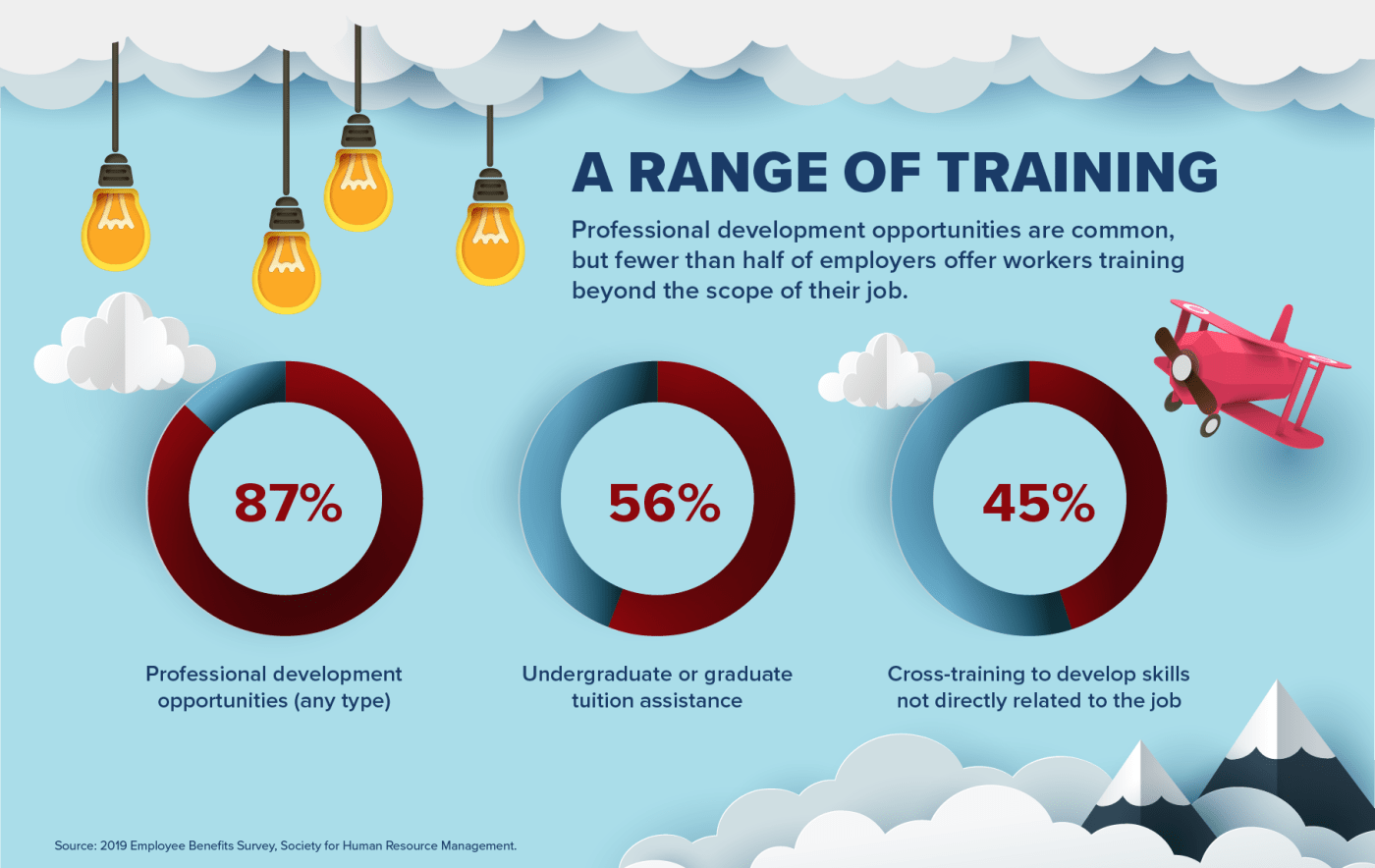

Companies might be considering outskilling, but few are actually doing it. In fact, some statistics indicate that employers are providing little in the way of skills improvement. According to survey results released by PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) earlier this year, fewer than 1 in 5 global CEOs believe their organizations have made “significant progress” in establishing an upskilling program. And only 33 percent of employees said they feel they were given opportunities to develop digital skills outside of their normal duties.

“Workers need to be convinced that companies are engaging in upskilling efforts to improve employability, not just to improve the bottom line,” the consulting company’s report said.

The survey didn’t specifically ask about outskilling, and even if companies start to offer such programs, they probably won’t use the term outskilling. The word carries a negative connotation, notes Cat Ward, managing director at JFF (Jobs for the Future), a Boston-based nonprofit working to improve the U.S. workforce and education systems. “From the worker’s point of view, who wants to be outskilled?” she asks.

The term also makes HR managers uncomfortable for a couple of reasons, says Mike Pino, partner and leader of the Workforce of the Future practice at PwC. First, outskilling programs may create litigation risks if, for example, only one group of employees in a massive layoff is offered outskilling and others are not. Second, there’s really no guarantee that outskilling will help the employee or the company. It’s a new and untested concept that could fail, Pino says. “So, a company could spend thousands of dollars per employee and not really touch [profit and loss].” Then you could have a situation where the company spent a lot of money and the employees spent a lot of time “and they still don’t have a job,” he says. “That’s why companies aren’t rushing to be the first one out of the gate.”

An Unexpected Opportunity?

The pandemic might create a petri dish that gives companies an opportunity to experiment with different workforce management practices. While decimating certain job categories, such as retail clerks and restaurant workers, the crisis has created new demand in other categories, like warehouse and delivery workers. Companies are exploring how they might train the former to become the latter. In April, for example, a group of companies and trade associations (including the Society for Human Resource Management) announced People + Work Connect, an employer-to-employer platform that matches companies that have had layoffs with companies needing more workers.

In addition, some third-party companies are getting into the outsourcing business.

Meanwhile, companies can take simple, informal, unilateral actions.

“It doesn’t have to cost significant dollars to start doing this,” Ekhtiari says. “It could just be a CEO simply picking up the phone, making a call across the street to an organization [and] saying, ‘We have to let these workers go. Can you prioritize them in your hiring?’ ”

With trillions of stimulus dollars coming out of Washington, some people hope for government funding for outskilling programs. Ekhtiari notes that the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act provision that offers financial assistance to companies so they can continue paying employees’ wages could create breathing room for corporate leaders to develop creative programs.

Whatever companies end up doing or not doing, it will be remembered—by employees, consumers and prospective employees.

“Companies need to think about the other side of this curve,” Ekhtiari says. At some point, the pandemic will end. “Then, every candidate that you try to hire will ask the question ‘What did you do during COVID? What did your company do to help?’ ”

Tam Harbert is a freelance technology and business reporter based in the Washington, D.C., area.