Cutting Staff in Times of Crisis

The coronavirus has caused businesses to shed jobs at a record pace. What are the business and legal implications?

When the National Zoo in Washington, D.C., closed its doors to visitors in March to help control the spread of the coronavirus, Kate Sizemore was forced to make a difficult decision. With the zoo's revenue suddenly reduced by the shutdown, Sizemore, the chief human resources officer at the nonprofit Friends of the National Zoo, furloughed three-quarters of the 180 employees who run the zoo's educational programs, sell memorabilia, staff information booths and otherwise contribute to the visitor experience.

Of course, the zoo's circumstances are far from unique. The COVID-19 pandemic has caused millions of Americans to suspend their normal daily activities and stay at home. The widespread commitment to public safety, in many instances undergirded by local and state shelter-in-place mandates, has had a catastrophic impact on the economy and resulted in massive job losses.

As of late April, more than 30 million Americans had filed for unemployment benefits—the most dramatic rise in claims ever recorded. Virtually all of the job gains made in the decade since the Great Recession were erased in a matter of weeks.

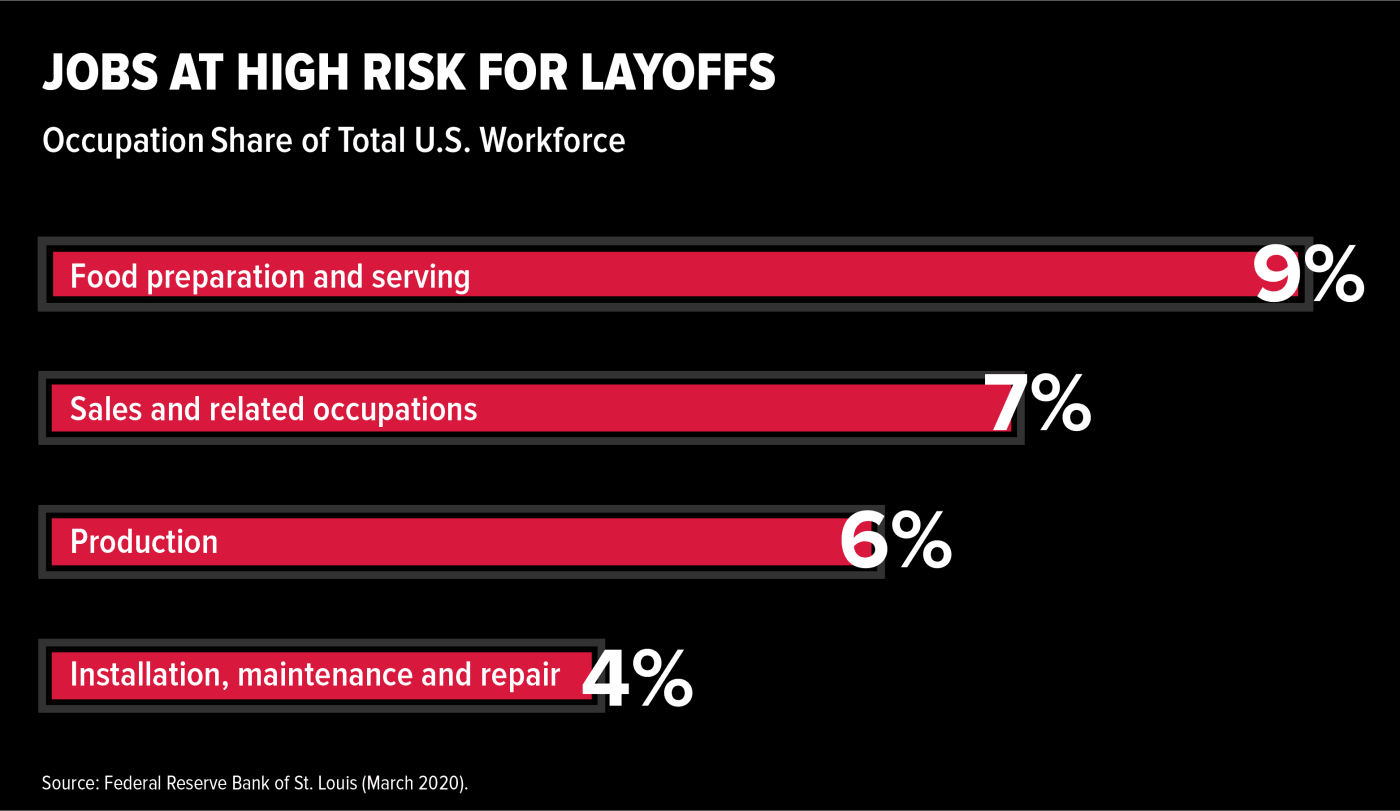

Despite the passage of historic economic relief legislation that includes hundreds of billions of dollars in forgivable loans to businesses that keep their employees on payroll through the downturn, there's mounting evidence that the job cuts are far from over. A research brief issued by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis in late March estimated that more than 47 million Americans could be laid off by the end of second quarter of 2020.

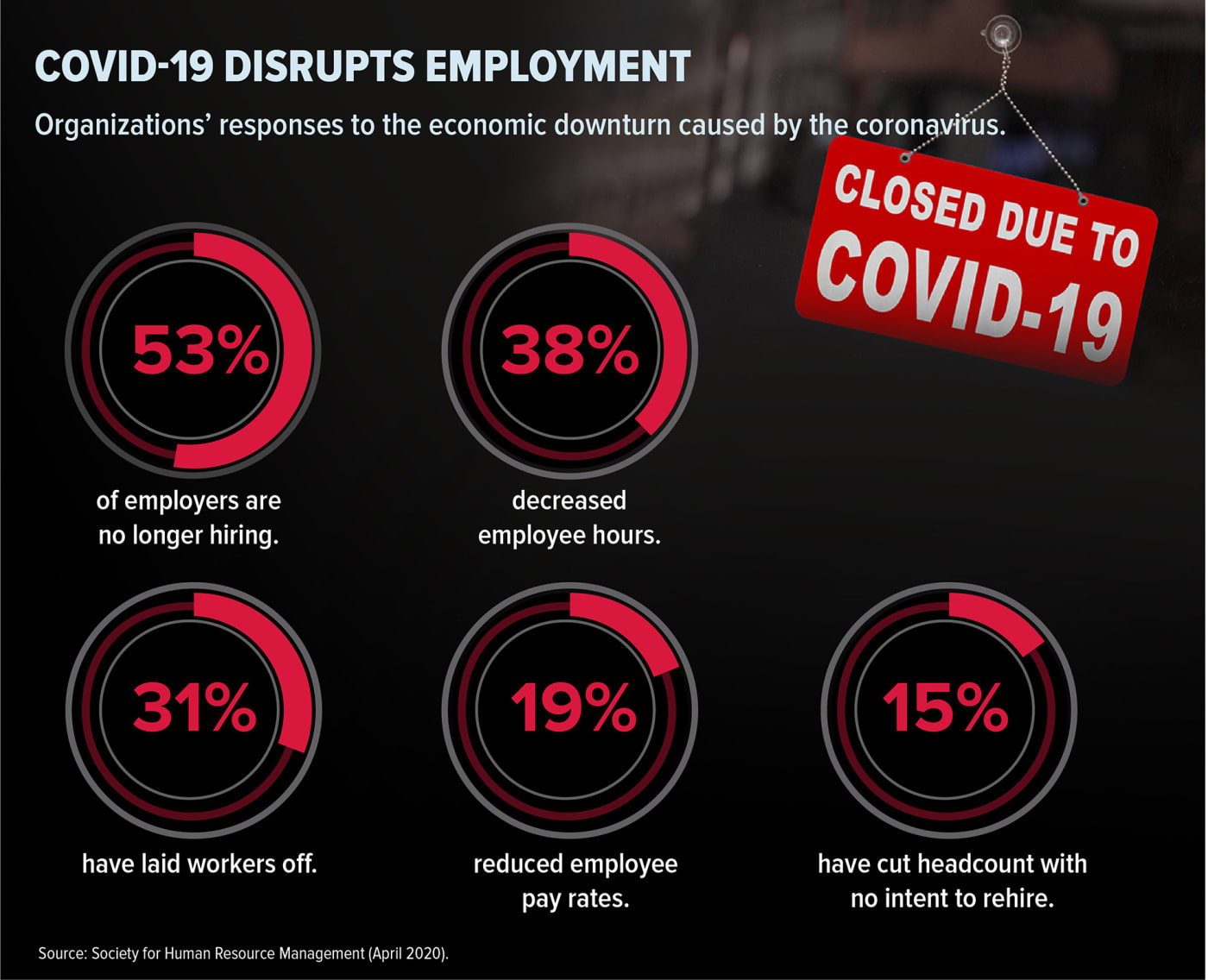

The gloomy picture was confirmed in research from the Society for Human Resource Management released in April, as many employers have had to make staffing changes to stay solvent.

The promise of free federal money to employers who maintain payroll is providing little solace to business leaders when they have no way of knowing how long the crisis, or the money, will last.

“We want to bring everyone back,” says the business manager for a Maryland physical therapy practice. The firm furloughed three employees in mid-March when doctors began delaying nonessential procedures such as hip and knee replacements that generated physical therapy referrals. But even after being approved for financial aid from the state and the federal government, the manager, who asked that neither she nor the business be named because of the sensitivity of the issue, says she’s unsure about whether to reinstate the furloughed workers now or when business gets back to normal.

“We don’t want to shoot ourselves in the foot by having to turn around and lay these folks off again,” she says.

For many organizations, staff cuts provide a first line of defense against financial devastation. But business leaders contemplating layoffs, as well as when and how to start recalling employees, must work through myriad strategic considerations and navigate a complex tangle of federal and state laws governing pay, benefits and notice requirements. The decisions they make now will affect the ability of their businesses to recover as the economy rebounds.

Slashing Payroll

Many employers have little choice but to reduce payroll in response to income lost during the pandemic. But the decision of how to accomplish that has financial and legal implications for the business and its employees.

Furloughs generally involve reduced work hours or temporary leave without pay. But furloughed employees remain on the books, and they often continue to receive benefits and health coverage. In contrast, when an employer announces layoffs, the general assumption is that the employees aren’t coming back.

When a business expects revenue to rebound soon, furloughs might be the best option. “If a company wants to hit the ground running when things improve, a furlough is the better choice,” says attorney Chris Lamb of Fortis Law Partners in Denver.

Furloughs became unavoidable at one large Greenville, N.C., orthopedics clinic when doctors in the area stopped performing elective surgeries. So far, three employees have been placed on unpaid leave at Orthopaedics East & Sports Medicine Center, but, to forestall further cuts, hourly employees are working 30 hours, rather than 40, and managers, directors and physicians have taken a “significant pay cut,” says Cindy Cronkhite, assistant administrator. Merit-based pay raises have also been frozen for the remainder of the year.

Some companies, such as several large news organizations, are opting for graduated salary reductions where higher-paid employees take the largest cuts.

Cutting the hours of salaried, white-collar workers, however, may have costly unintended consequences. If done incorrectly, it could result in a change in the workers’ exempt status under the Fair Labor Standards Act, making them eligible for overtime pay.

Larger organizations contemplating significant staff cuts must comply with federal and state laws requiring employers to give workers advance notice of a shutdown. Failure to follow the rules can result in penalties that accrue daily. Companies that announced layoffs during the early days of the pandemic may be exempt under the unforeseen business circumstances exception of the laws. But the window for employers to fall back on that exception may be closing.

“The longer we go, the more difficult it’s going to be to argue that [the layoff] was unforeseen,” says attorney David Pryzbylski, a partner at Barnes & Thornburg LLP in Indianapolis.

At least one state, California, has suspended its employer-notification requirements during the crisis to give cash-strapped employers additional flexibility. Moreover, rules governing benefits, unemployment insurance compensation and payments of accrued leave vary by state, and several states have changed their laws in response to the crisis. “Employers would be well-served to take a good look at their existing policies, especially with regard to pay and benefits,” Lamb says. “Read your benefit plan. And if you have any questions, talk to counsel.”

Furlough, Layoff and Reductions in Force: What’s the Difference?

Furlough, Layoff and Reductions in Force: What’s the Difference?

All three of these terms describe actions that are intended to achieve cost savings by reducing a company’s payroll costs. Even though the words have been used interchangeably, their true meanings are quite different.

FURLOUGH

A furlough is considered to be an alternative to layoff. When an employer furloughs its employees, it requires them to work fewer hours or to take a certain amount of unpaid time off. For example, an employer may furlough its nonexempt employees one day a week for the remainder of the year and pay them for only 32 hours instead of their normal 40 hours each week. Another method of furlough is to require all employees to take a week or two of unpaid leave sometime during the year.

Employers must be careful when furloughing exempt employees so that they continue to pay them on a salary basis and do not jeopardize their exempt status under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA). A furlough that encompasses a full workweek is one way to accomplish this, since the FLSA states that exempt employees do not have to be paid for any week in which they perform no work.

An employer may require all employees to go on furlough, or it may exclude some employees who provide essential services. Generally, the theory is to have the majority of employees share some hardship as opposed to a few employees losing their jobs completely.

LAYOFF

A layoff is a temporary separation from payroll. An employee is laid off because there is not enough work for him or her to perform. The employer, however, believes that this condition will change and intends to recall the person when work again becomes available. Employees are typically able to collect unemployment benefits while on an unpaid layoff, and frequently an employer will allow employees to maintain benefit coverage for a defined period of time as an incentive to remain available for recall.

REDUCTION IN FORCE

A reduction in force (RIF) occurs when a position is eliminated without the intention of replacing it and involves a permanent cut in headcount. A layoff may turn into a RIF, or the employer may choose to immediately reduce their workforce. A RIF can be accomplished by terminating employees or by means of attrition.

When an employee is terminated pursuant to a reduction in force, it is sometimes referred to as being “riffed.” However, some employers use layoff as a synonym for what is actually a permanent separation. This may be confusing to the affected employee because it implies that recall is a possibility, which may prevent the employee from actively seeking a new job.

Companies contemplating layoffs inevitably face thorny issues surrounding whom to cut.

"Layoffs can't just be about cutting, cutting, cutting," says Adam Calli, SHRM-SCP, founder and principal consultant at Arc Human Capital in Washington, D.C. "You have to make sure you still have the talent and skills you need to survive so you can get to the other side."

Sizemore worked with the zoo's management team to distinguish essential from nonessential workers and then to determine the timing of the employment actions. That meant first laying off the 100 employees who came in direct contact with visitors, including retail workers and information booth staff. "We just knew there would be no more work for them," she says.

Nearly 50 full-time employees were furloughed two weeks later, after zoo officials took a closer look at what jobs would best serve the organization during the crisis. Many of those selected to stay were fundraisers or those who worked on educational materials, which have been in high demand since schools shut down, Sizemore says.

"We really had to analyze our business strategy and consider how, if at all, the public would want to interact with cultural institutions. We're still looking at ways to drive membership."

Sizemore, who has worked at other organizations during tough times, says she is well-aware of the risks of laying off workers, including hourly workers who did not qualify for health or retirement benefits and may not wait around for the zoo to hire them back. "There will definitely be a ramp-up," she says, "and definitely we are going to lose people."

Avoiding Discrimination Claims

Businesses that cut staff must be mindful of the many state and federal laws designed to prevent discrimination against racial and ethnic minorities, older workers and other legally protected groups of workers, says Harold Datz, an employment law professor at Georgetown University and George Washington University law schools. "Organizations have to look closely at their demographics to make sure the cuts don't disproportionately harm a protected class," he says. That applies equally to furloughs and layoffs.

Business leaders have to be particularly careful when cutting whole departments if such a decision would disproportionately affect a protected group. "A business would need to be able to show a legitimate business reason for closing that department," Datz says.

There may be no single best way to avoid a discrimination claim. But one option is to keep employees who have the longest job tenure. Seniority "allows employers to keep their most experienced workers," says Datz, who favors this approach. "During this pandemic, seniority will give employers a rational and well-understood defense against those who complain they were let go unfairly."

Calli, on the other hand, encourages businesses to consider an individual's contribution to the organization when deciding whom to cut and whom to bring back when conditions improve. "It's times like this that I remind employers that your performance management system is so important. I'm not bringing back someone who's a master of mediocrity. I'm bringing back the best contributors."

Performance data also may help an employer fend off a discrimination complaint from an employee claiming to have been unfairly targeted during a layoff or overlooked when other furloughed employees are called back, Calli says.

Alternatives to Staff Cuts

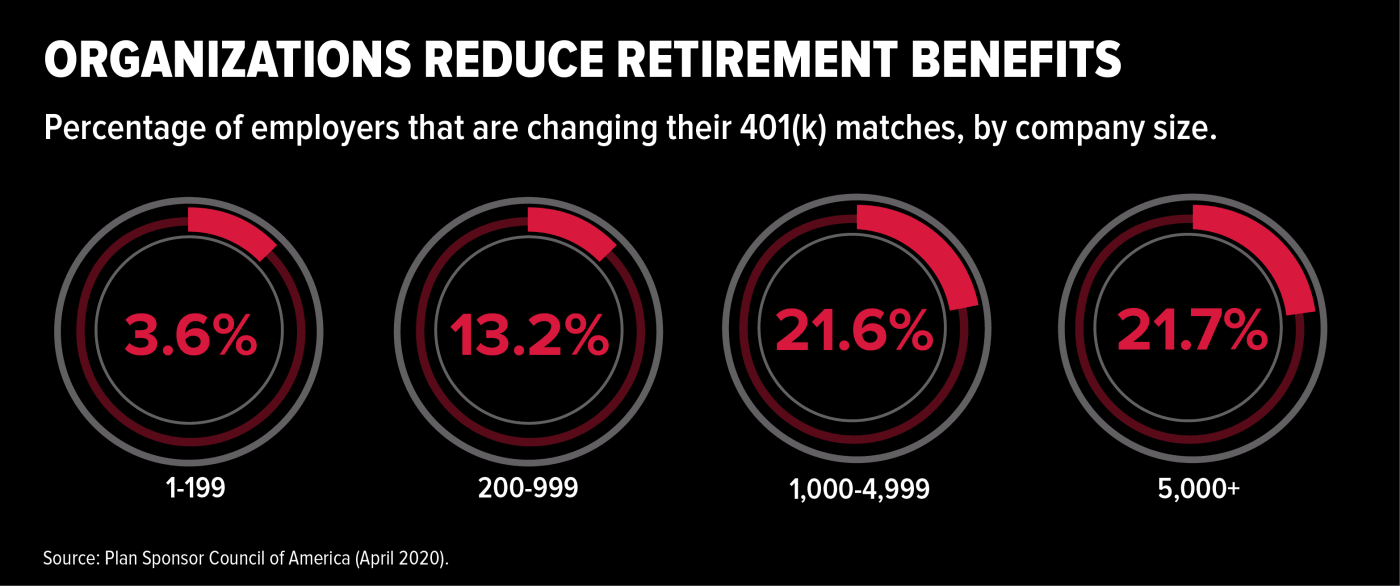

Employers that must reduce costs have options other than layoffs and furloughs. These include reductions to employees’ 401(k) matches and delays to retirement benefits funding.

A typical employer matches 50 percent of employees’ 401(k) contributions up to 6 percent of their salaries. In the months following the September 2008 stock market crash, more than 200 major companies rushed to reduce or suspend those matching contributions, affecting nearly 2.5 million plan participants, according to the Center for Retirement Research.

A similar trend seems to be emerging now, according to a Plan Sponsor Council of America survey, as more than 20 percent of large organizations are suspending matching employer contributions. Fewer smaller organizations (3.6 percent) are taking the same step, the council found.

Some employers may be able to delay funding 401(k) matches until later in the year after the financial picture, hopefully, has improved, says Amy Reynolds, a partner at Mercer in Richmond, Va. She also recommends that employers consider suspending automatic triggers that increase employee—and potentially employer—contributions.

Helping Workers

Now, more than ever, employers need to be sensitive to employees' emotional and financial needs. Here are some tips for helping workers who are laid off or furloughed survive the crisis.

Help employees navigate the unemployment benefits system. At a minimum, tell them where to apply for benefits and promptly answer their questions.

Stress that there's no stigma to seeking unemployment benefits.

Be clear and honest in communications with all workers. Let furloughed employees know what their prospects are of being brought back. And let those who remain on payroll know if more cuts might be necessary and when the cuts might happen.

Commit to spending federal or state financial assistance on salaries; loans made through the federal Paycheck Protection Program and used to maintain payroll may be forgiven.

Refer employees to sources of private relief, such as those established by the National Restaurant Association Educational Foundation and the American Hotel and Lodging Association.

Many employers face difficult choices as they take steps to weather the economic storm brought on by the pandemic. Unfortunately, in many cases, furloughs and layoffs will be unavoidable. But leaders will be judged by the actions they take today to support their workforces and keep their businesses afloat.

Rita Zeidner is a freelance writer based in Falls Church, Va.

Explore Further

SHRM provides advice and resources to help businesses manage furloughs and layoffs and support employees during the COVID-19 pandemic.How to Conduct Virtual Layoffs—Compassionately

Getting laid off is never easy, but the coronavirus crisis has made the experience even more harrowing. It’s true that the pandemic has transformed workplace norms seemingly overnight. But that doesn’t mean our compassion and respect for people can go out the window.

A Legal Guide on Shifting from Furloughs to Layoffs

An increasing number of employers are creating plans to lay off furloughed employees, formally ending those employment relationships. If you are in that situation, here are some of the more salient issues to consider.

Unemployment Insurance: Eligibility and Benefits Issues

Unemployment Insurance and Furlough Q&As

HR Q&A: Can We Keep Furloughed or Laid-Off Employees on Our Group Health Plan?

When Employers Must Cut Their 401(k) Contributions to Stay Afloat