When Deb Dagit attended the signing of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) on the South Lawn of the White House on July 26, 1990, she, along with the approximately 3,000 other people gathered, believed the new law would help reduce stigma and attitudinal barriers toward Americans with disabilities.

Who among them might have thought of the opportunities and challenges that artificial intelligence would afford to improve access on the law’s 34th anniversary? Yet today, AI poses the possibility of removing even more barriers for people with disabilities—and, without human oversight, creating obstacles, too.

Dagit, a diversity consultant with Deb Dagit Diversity in Naples, Fla., is an influential disability rights advocate. In her experience, business leaders are often at the forefront in advocating for candidates and employees with disabilities.

“Disability inclusion and accessibility are nonnegotiable for a contemporary business,” Dagit told SHRM Online. Modern-day businesses are immersed in AI, which “can be a very helpful tool for people with disabilities, just like everyone else, if used judiciously,” she added.

But although technological advances can and have improved inclusion and accessibility, some age-old obstacles for people with disabilities remain.

“While we have come a long way in so many regards, stigma remains stubborn, particularly for those living with mental health conditions,” Dagit said. “Many physical, sensory, chronic medical, and neurodiverse disabilities are accompanied to varying degrees by depression and anxiety due in large part to how people with these conditions are regarded and treated.”

ADA’s Benefits

Prior to the ADA, people with disabilities weren’t as visible in society, said Taryn Mackenzie Williams, assistant secretary of Labor for disability employment policy and head of the U.S. Department of Labor’s Office of Disability Employment Policy in Washington, D.C.

The ADA’s “underlying promise is inclusion,” she said. Prior to the law, people without disabilities didn’t have the opportunity to interact with people with disabilities as much as they do today, whether in the workplace or out and about in the community, she noted. That inclusion has led to more contributions from individuals with a variety of disabilities.

“We know that workplaces benefit from varied perspectives—that groups that comprise people with different backgrounds and different perspectives perform better than homogeneous ones,” Williams said.

That’s because varied perspectives produce multiple solutions to problems, and it’s typically a combination of elements of these different solutions that winds up working best. “Usually, it’s a solution that no one person would have come up with on their own,” Williams said.

More Progress Sought

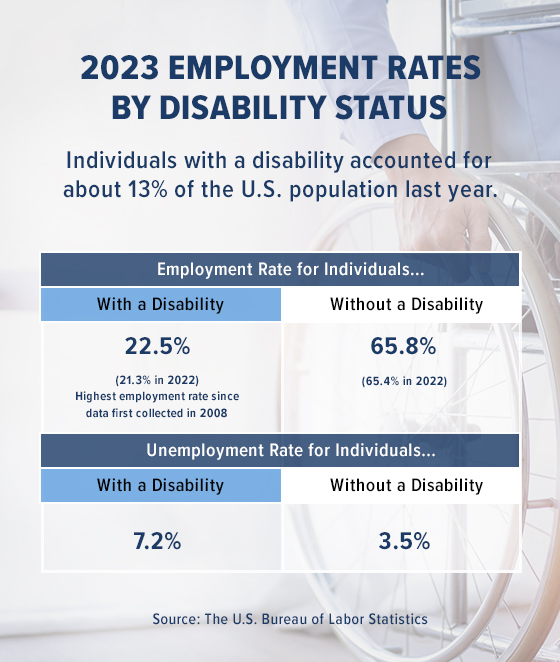

While the ADA has benefited many, a significant number of people with disabilities still face barriers. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics:

- Last year, the employment rate for individuals with a disability was 22.5% versus 65.8% for persons without a disability. The unemployment rate for individuals with a disability was 7.2% versus 3.5% for persons without a disability. (See infographic.)

- As of June this year, the employment rate for individuals with a disability remained 22.5% but dropped slightly to 65.7% for those without a disability. Meanwhile, the unemployment rate for people with disabilities jumped to 8%—almost double the 4.1% unemployment rate of people without disabilities.

“People who do not have a disability think that the ADA solved all problems, but it did not, something many people with disabilities know only too well,” said Beth Sirull, CEO of the National Organization on Disability, based in New York City.

Some people also think accessibility, especially physical accessibility that is required by the ADA, is part of the fabric of the U.S., she added. “While curb cuts are ubiquitous and used by people in wheelchairs as well as parents with strollers, bike riders, and others, there are other accessibility issues that remain unaddressed,” Sirull said.

Technological barriers in particular are a persistent problem.

“As technology is constantly changing, the tools and implementation of digitally accessible content often fall behind,” Sirull said. “Here we are, 34 years after the passage of the ADA, and the vast majority of websites remain inaccessible.”

AI and Access

While new technology may create barriers and come with challenges, AI is likely to assist those with certain disabilities, said Anne Marie Estevez, an attorney with Morgan Lewis in Miami.

AI allows for greater customization of certain assistive technology solutions because algorithms can be trained based on an individual’s needs, said Carolyn Rashby, an attorney with Covington in San Francisco. Such technology may enable people with disabilities to perform certain jobs that they otherwise couldn’t, she said.

For example, certain text simplification algorithms may make written documents more accessible to neurodivergent individuals; live captioning of in-person, video, and phone calls may make it easier for individuals who are deaf or hard of hearing to participate; and image recognition technology can provide feedback to blind or partially sighted people through speech describing the images, Rashby said.

However, Sirull noted that “artificial intelligence creates both new barriers and new opportunities for people with disabilities.” In particular, AI algorithms may be subject to bias, she cautioned. That said, advances in technology make it easier and quicker to build digital accessibility into the recruiting process through automated tools.

HR must be vigilant in its oversight of AI and steer clear of its pitfalls. Otherwise, for example, Rashby said if an employer uses voice or facial analysis technologies to evaluate an applicant’s communication skills and abilities, people with certain disabilities—such as speech difficulties or autism—might be screened out, even if they are qualified for the job.

Or some employers may use algorithms to evaluate candidates’ performance on certain tests or assessments, she added. A blind or partially sighted candidate who performs poorly on a computer-based test that requires them to see might get passed over based on the algorithm, even if that candidate could otherwise perform the job, Rashby said.

AI creates many opportunities to remove barriers, but because it is still developing and changing, it needs to be used with caution, said Kristina Launey, an attorney with Seyfarth in Sacramento, Calif.

For example, many videoconferencing systems have the capability to provide automatic captioning of what is said. “While the accuracy of that AI-generated captioning has improved greatly over the years, it still is not perfect and can get some words wrong,” Launey said. “At the same time, if a captioner is not available, having the automatic captioning can help people with hearing-related disabilities communicate.”

Screen readers assist blind and partially sighted individuals by converting text and other on-screen elements into synthesized speech or Braille, allowing users to access and interact with digital content. Through keyboard shortcuts and audio cues, screen readers should enable seamless navigation and provide an inclusive digital experience. AI solutions for websites might interfere with screen readers by introducing dynamically changing content that may not be readily accessible or interpretable, thus hindering otherwise seamless navigation.

Some blind and partially sighted plaintiffs have filed ADA lawsuits claiming that an AI solution interfered with the screen reader they use, thereby impeding rather than improving accessibility, Launey said.

AI isn’t perfect yet, but many users with disabilities have still found it to be extremely helpful. “It can save time for people who have difficulty typing, reading, writing, calculating, researching, creating documents, etc.,” Dagit said. “For individuals who may experience challenges that make it harder to do things quickly, it can boost productivity and reduce anxiety.”