Part 1

How Do You Decide Who Stays and Who Goes?

When RIF Selections Go Wrong

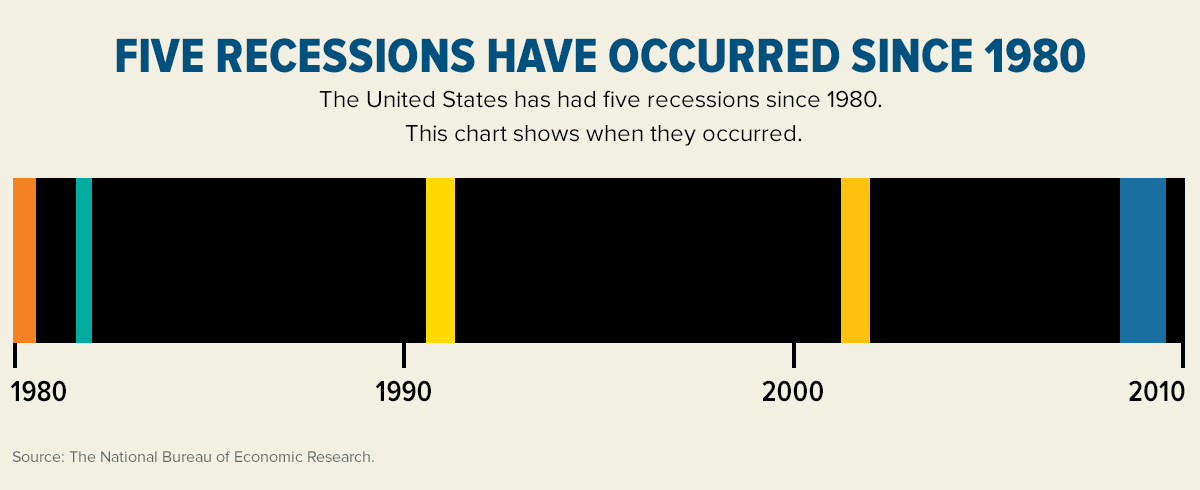

The trade war between the United States and China, plus the length of time that has passed since the last recession, have CEOs and HR leaders wondering when the next recession will be. Is it just around the corner? Are we entering it already? Or is it years away?

Now is the time to prepare for the next recession, since the economy, like the stock market, does not expand indefinitely. And whether a recession happens later rather than sooner, layoffs occur more often than you might think. How can HR make them as fair as possible?

The right selection criteria, avoiding adverse impact on protected groups of employees, announcing the layoff decision and parting ways on the best terms possible can make a difference.

Are We Headed for a Recession?

The economy can be in a recession before the recession is widely recognized as having begun. The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) didn't note the start of the Great Recession, which began in December 2007, until December 2008. "However, it's pretty clear once an economy has been in a recession for a couple of months," said Ryan Sweet, director of real-time economics for Moody's Analytics in West Chester, Pa.

Although the media often define a recession as two consecutive quarters of negative gross domestic product growth, that description isn't accurate, according to Sweet. The NBER defines a recession as a "significant decline in economic activity spread across the economy, lasting more than a few months." The NBER examines several indicators, including gross domestic product and gross domestic income, payroll employment, incomes, wholesale retail sales and industrial production.

"It's possible that not one single event but rather a combination causes enough damage to the economy and psyche that a recession results," Sweet said. "For example, a perfect storm would be an escalation in the U.S. and China trade tensions, sudden tightening in financial market conditions and Brexit all occurring around the same time."

At least one organization, the liberal American Bridge 21st Century, disputes that the economy is strong, noting that more than 716,341 workers have been notified of plant closings and layoffs thus far while President Donald Trump has been in office. The figure is based on the organization's review of Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification Act notice filings from Jan. 20, 2017, to Aug. 19, 2019. Even if the economy is, in fact, strong, these figures show that many layoffs occur when there isn't a recession. So regardless of whether a recession is imminent, employers need to be ready for the possibility of changed circumstances or repositioning in their business that necessitates a reduction in force (RIF).

Reasons for Layoffs

Layoffs may occur for many different, legitimate reasons. These reasons include eliminating or downsizing a business unit that is not performing well, laying off employees with performance issues, or closing an office or plant, noted Evan Parness, an attorney with DLA Piper in New York City.

Ron Taylor, an attorney with Venable in Baltimore, said that common reasons for a RIF include:

A need or desire to restructure. An employer may choose to eliminate duplicative positions following a merger or acquisition, or realign functions to achieve efficiencies.

To reduce costs. A company might lay off workers in reaction to reduced demand for a product or to cut labor costs.

To eliminate a function. Employers could outsource a function that the company can no longer perform efficiently, or cease a function made unprofitable by competition or obsolete by technological advances.

To relocate. Relocation of operations to a new site, city, state or country may result in layoffs in the old location.

Organizations must periodically rightsize, said Joyce Chastain, SHRM-SCP, president of Chastain Consulting in Tallahassee, Fla. Often in times of growth, companies add beneficial but nonessential positions. Those positions likely will be eliminated in a RIF.

Keep workers apprised of company finances to the extent possible so they are less surprised if layoffs occur, recommended Lynne Anne Anderson, an attorney with Drinker Biddle in Florham Park, N.J.

'The Most Critical Decision'

An employer's choice of selection criteria to determine who will be laid off "is the most critical decision made in the course of a RIF," said Gerald Hathaway, an attorney with Drinker Biddle in New York City.

[SHRM members-only resource: Reduction in Force (RIF) Strategy and Selection Checklist]

Three main methods of selecting employees for layoff are "last in, first out," in which the most recently hired employees are the first to be let go; reliance on performance reviews; and forced rankings, said Kelly Scott, an attorney with Ervin Cohen & Jessup in Los Angeles.

The more objective the selection criteria, the more defensible they are if later challenged in court, said Molly Batsch, an attorney with Greensfelder in St. Louis. Seniority-based criteria are typically easier to defend than subjective performance-based criteria, she said.

However, the laid-off workers might feel that using seniority as a basis for choosing whom to lay off is unfair, said Steve Wolfe, executive vice president of operations at Addison Group in Chicago.

If an employer relies on performance-based criteria in selecting who will be laid off, it should minimize the level of subjectivity. For example, performance-based criteria that account for objective sales targets or other objective performance metrics are easier to defend in court than performance-based criteria that consider only managers' opinions, Batsch said.

If managers' opinions are factored in to the decisions to let employees go during a layoff, their opinions should be supported by documentation, such as performance evaluations, and scrutinized by the RIF decision-makers.

Most employers prefer performance-based layoffs, as they like to keep the best workers, Scott said. This isn't always possible if a company hasn't kept proper records. If documentation is inadequate, forced ranking is typically done, he said. Employees then are ranked from 1 to 10 using all the criteria the employer has, such as absenteeism and the ability to perform different functions. The employer keeps the employees with the best scores.

"The key is coming up with the criteria by looking at job descriptions and getting management together," Scott said. "The more input, the better."

Looking to the Future

David Froiland, an attorney with Ogletree Deakins in Milwaukee, said that "while lawyers sometimes gravitate toward [selection] criteria that are objective and mathematical—such as length of service or absolute sales numbers—these criteria often fail to reflect the skills and strengths that the business needs to change and grow in the future."

The employee with the most seniority may not be the best performer. The top sales employee with a declining book of business or in a declining sector may be less attractive than the fifth highest sales representative who is growing business or works in a strategically important sector, he explained.

"Ideally, the selection criteria should reflect factors that will be most important to the ongoing business after the RIF is implemented," Froiland said. "Maybe this is a particular skill set. Maybe it is proficiency in a range of software applications or other technologies. Or maybe it is a mix of factors, as ranked in a matrix."

PART 2: When RIF Selections Go Wrong