Companies Seek to Boost Low Usage of Employee Assistance Programs

New providers and services are among the changes being rolled out by employers to make EAPs more attractive.

American employees are stressed. Or anxious. Or depressed. Or all three. Employees know it—they feel it, and the blaring headlines in the media regularly reinforce it. Employers know it—their consultants are bombarding them with studies and reports highlighting the problem and its consequences.

Case in point: Job-related stress is the nation's leading workplace health problem, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and productivity losses from absenteeism related to stress cost employers $225.8 billion, or $1,685 per employee, each year. In the worst-case scenarios, workers with serious mental health problems can be dangerous to themselves and others.

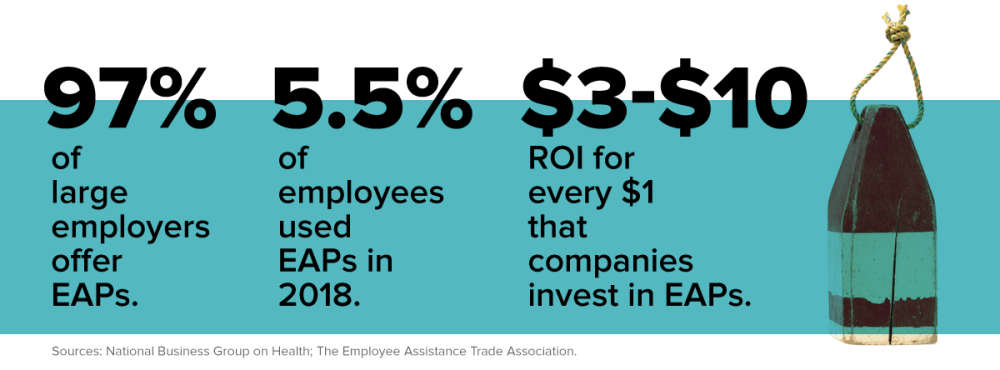

Employers are trying to help, instituting wellness programs, flexible schedules, yoga classes and meditation instruction. Yet they struggle to understand why only a tiny minority of workers take advantage of a marquee employer-provided tool to help them improve their mental health: employee assistance programs (EAPs). Nearly all companies now offer EAPs, which typically give employees immediate phone access to a counselor, a limited number of free sessions with a mental health care professional and referrals to therapists. In recent years, employers have added other options to help employees achieve work/life balance, such as links to child care and elder care providers as well as sessions with lawyers and financial planners.

Yet EAP utilization averages below 10 percent, according to multiple studies, consultants and human resource professionals. The Washington, D.C.-based National Business Group on Health, for example, found that median utilization in 2018 was 5.5 percent.

"The question of usage is a consternation," says LuAnn Heinen, vice president of well-being and workforce strategy at the nonprofit, which is dedicated to lowering the cost of health care. "Stress and anxiety are at an all-time high. The need is so great."

Distrust, Poor Promotion Stymie EAPs

Heinen and others say the continuing stigma around mental health keeps some employees from taking advantage of EAPs. Even though the American Psychiatric Association says 1 in 5 adults will struggle with mental illness during their lifetime, many individuals view such conditions as personal flaws rather than medical issues. Others may fear that the information discussed won't be kept confidential. That distrust stems from EAPs' origins in the 1950s as employer-run and -mandated alcohol treatment programs.

"We preach confidentiality at every turn," says Jason Richmond, a senior vice president at Beacon Health Options in Boston, which has an EAP utilization rate of about 5 percent. "We tell people on the phone, on the website, everywhere."

In many cases, the reason for underutilization is simply that companies don't aggressively promote the programs, so employees don't know they exist.

"Usage is abysmal," says Christopher Calvert, senior vice president for health at New York City-based Sibson Consulting. "Most companies aren't communicating their EAPs well. It wouldn't occur to employees to call."

Employers Try New Approaches

There are signs that companies are rethinking their approaches. In a letter to employees last September, Starbucks Chief Executive Officer Kevin Johnson said the Seattle-based coffee company would be offering an enhanced EAP to connect more workers with care to meet their specific needs. Nearly half of companies have either enhanced their EAP services within the last two years or changed EAP vendors to provide a more robust offering, according to a 2019 survey by Mercer. Expanded EAP offerings include onsite counseling services and online programs that employ cognitive behavioral therapy.

EAPs have remained in employers' benefits packages despite low usage because they're relatively inexpensive. They cost between 75 cents and $1.50 per member per month, regardless of how often they're tapped, experts say, though richer plans can go up to $2. Some EAPs don't cost employers anything extra because they're included in the already-purchased health or life insurance plans. Newer entrants to the EAP industry, such as Burlingame, Calif.-based Lyra Health Inc. and New York City-based Spring Health, partially base rates on usage, so they tend to be more expensive.

"I would never not have an EAP," says Tracie Sponenberg, SHRM-SCP, chief people officer at the Granite Group, a plumbing supply wholesaler in Concord, N.H. "It's low-cost, and if two people get something out of it, the program is worth it."

Last year, she switched providers to save money and offer new benefits. Like many EAPs, the company's former provider included services such as crisis management and training. Sponenberg says Granite barely used such offerings, so the EAP wasn't worth the $17,000 price tag. Now the company pays $5,000 a year and employees can access mental health benefits online and through telemedicine. The cost also includes perks such as party and vacation planning that are offered to help employees avoid time-consuming, and sometimes frustrating, tasks that keep them from doing their jobs.

"There's more of a move to provide services that make employees' lives easier," Sponenberg says.

Still, experts say the vast majority of employees use EAPs for the mental health benefits. And some suggest that EAPs are having a more positive effect than people realize. Mark Attridge, head of his own eponymous EAP consulting company in Minneapolis, estimates that perhaps 15 percent to 30 percent of employees need help on the mental health front and that EAPs are capturing one-third to one-half of them. Many others are probably getting help without the EAP, Attridge says.

In a study of roughly 24,300 employees collected from 30 EAPs, Attridge found that absenteeism dropped 27 percent for workers who used an EAP. The study, published in the International Journal of Health & Productivity, also discovered that the employees' engagement at work grew 8 percent, while life satisfaction jumped 22 percent.

Attridge says EAPs' effectiveness is ultimately up to the employer. "What do they want their EAP to be?" he asks. "Do they want to maximize it? It's the company goal that's the bigger issue."

Cerner Corp. decided it wanted to enrich its EAP by offering more services as part of a larger campaign focusing on the importance of mental health. In 2018, the company switched providers and rebranded its EAP as "My Life Resources," which now includes more-diverse benefits such as legal services, financial coaching, identity theft insurance, text therapy and online cognitive behavioral therapy.

"We wanted to add a cross section of services," says Emma Tapscott, manager, Worldwide Wellness-Healthe at Cerner, a North Kansas City, Mo.-based provider of health care technology and information. "The sources of stress are complex, and we wanted to present different ways to alleviate it."

She says that, as a technology company, Cerner was especially interested in providing multiple Web- and phone-based ways for employees to access counseling.

A Boost from Technology

A Boost from Technology

Tech solutions have been a focus of most EAPs in recent years, and the newer companies that have sprung up say embracing different modalities to provide services sets them apart from older competitors.

Beacon Health started providing therapists via videoconferencing about 18 months ago and it has been quite popular, Richmond says. The technology gives patients access to therapists and counselors beyond their vicinity—a boon amid the shortage of mental health professionals. "It increases employees' options," he says. "They can see someone three hours away."

Companies such as Lyra and Spring Health are using technology as part of what they say is a more evidence-based approach to mental health care. Each was started in the last five years and takes a similar approach to care. Employees answer a short online survey to determine their diagnosis and which type of treatment would be best suited, and then can make appointments on the computer or via text instead of having to call therapists from a list. They have the option of using telemedicine to interact with their counselors, and the websites offer ways to address mental health issues without having to immediately seek counseling, such as through self-guided meditations.

"Not everyone is ready to talk to someone," says Susan Wyatt, head of customer success at Lyra.

Beyond the technology, these companies provide a greater number of counseling sessions than their more established counterparts. Rather than the typical six or seven free sessions, for example, Lyra offers between 16 and 25. Lyra and Spring Health both have lists of carefully selected providers who they know have availability. Often, lists provided by other EAPs include providers who are no longer accepting patients, Wyatt says.

However, neither Lyra nor Spring Health ensures that the providers are also covered under the employee's medical plan. That's crucial because out-of-network care can be expensive, and finding a new, covered provider mid-treatment can be stressful. Wyatt says Lyra can make accommodations in some circumstances.

But she adds that patients are more likely to be helped through Lyra's approach of offering more sessions than is typical and only covering therapeutic methods that have been scientifically proven to work. Freudian psychoanalysis, for example, isn't covered because it hasn't been scientifically validated, according to Wyatt. She says providing appropriate care, as opposed to just care, is critical to improving people's mental health.

Theresa Agovino is the workplace editor for SHRM.