Is the 4-Year College Model Broken?

Part 5: Boot camps, associate degrees and trade schools do what traditional education can't

Part 1

Promise of a 4-Year College Degree

Part 2

Students Aren't Learning Soft Skills

Part 3

College Grads Lack Hard Skills, Too

Part 4

How Business Leaders Influenced College Coursework

Part 5

Is the 4-Year College Model Broken?

Lighthouse Labs is a coding boot camp in Canada that trains software developers in as little as 10 weeks. Unlike in the traditional college classroom, Lighthouse students don't listen to lectures; their training is hands-on, and their teachers all have jobs in Web, software or mobile development.

The boot camp has instructed more than 20,000 Canadians and launched 1,500-plus graduates into careers as professional developers. About 97 percent of the school's graduates find jobs.

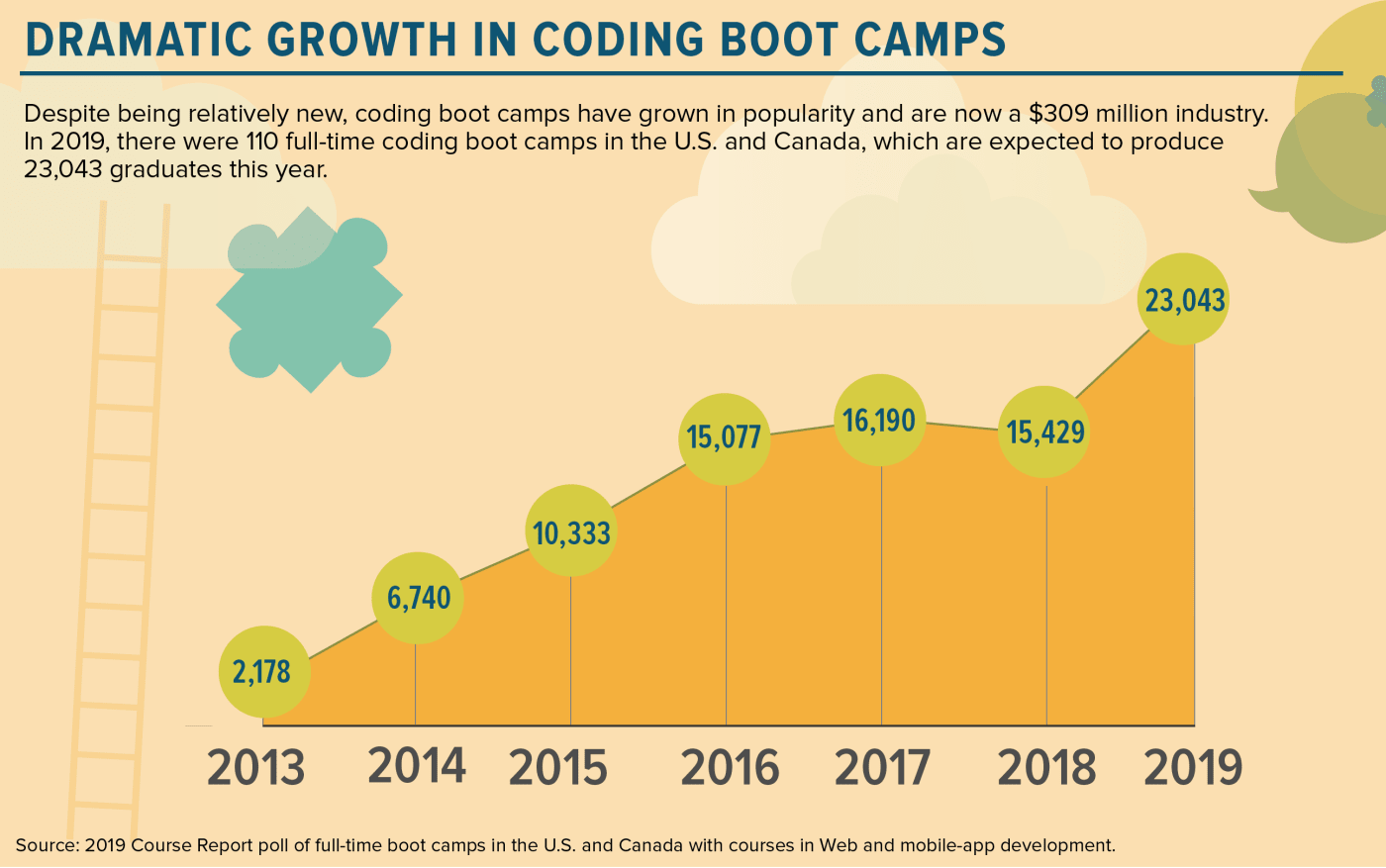

Coding boot camps are becoming more popular around the world as employers begin to value the blend of soft and hard skills, as well as hands-on experience, that these schools provide.

"Technological skills learned in a student's first year of college are no longer relevant when they graduate," said Jeremy Shaki, Lighthouse's CEO. "The No. 1 thing we teach at boot camp is that you must be constantly learning. That runs counter to what we see in people we find in college."

Outfits like Lighthouse Labs are springing up around the world—and doing quite well in the U.S.—at a time when young adults and their parents are expressing deep frustration with the U.S. college system: Each year, getting into good universities becomes increasingly competitive. The cost of a college education has skyrocketed, as has student loan debt. This year's college admissions scandal involving wealthy parents who allegedly paid hefty sums to get their children accepted to top U.S. universities demonstrated that coveted school spots can go to the wealthy, influential and deceitful but not necessarily to the honest, deserving and hardworking.

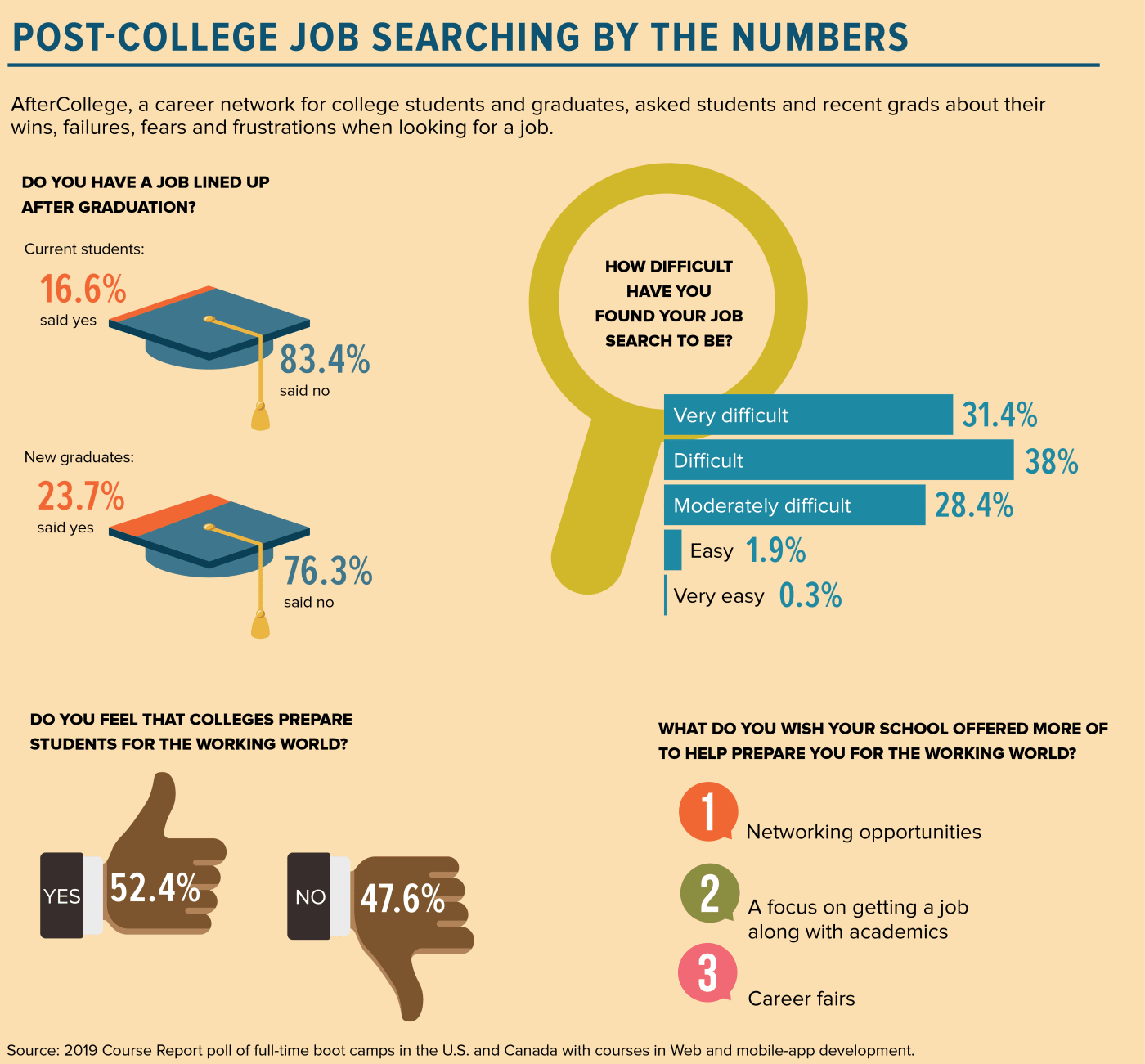

Add to that the fact that many employers see a disconnect between the skills they want in a new college graduate and the skills college graduates actually have, and one can see that the traditional bachelor's degree model may be falling apart.

"Apple, Microsoft, Google—all are changing how they hire, and they're not even looking at college degrees to the extent they used to," said Denise Leaser, SHRM-SCP, who is president of GreatBizTools, an HR management products and consulting services company in St. Paul, Minn., and whose daughter just graduated from California's Biola University. "Coding schools are doing a better job of incorporating soft skills into their programs, and they're more responsive than colleges. They can quickly modify a curriculum if it's missing something. In colleges, you might not know for four years that you're not preparing people the way employers need. I think the whole paradigm of education is going to be turned on its head."

Colleges and Students Think Grads Are Far Better Prepared than Employers Do

At 24, Sean Pour is the co-founder of SellMax, a nationwide car-buying service that he started in high school. Though his company was doing well by the time he was studying at San Diego State University, Pour felt obliged to finish his four-year degree in computer science.

Today, he's not sure that was necessary.

"[People] could train themselves [in computer science] just as well, maybe even better, at a specialized school," he said. "But people are still so focused on getting the four-year degree because it's what's expected of them. It's preconditioned into us from a young age, and we feel like a failure if we don't get one."

Today, Pour hires some college grads for entry-level positions. But he's having a harder time finding grads ready to supervise others.

"Colleges have trained people to simply follow instructions and not think on their own, which means they're not prepared for managerial roles. We've had significant trouble filling these higher-level positions at our company for this reason."

There is a disconnect between what business leaders need from workers and what higher-education institutions think they're producing. As far back as 2014, a Gallup study for Inside Higher Ed found that 96 percent of chief academic officers at higher-education institutions said their school is very or somewhat effective at preparing students for the world of work.

Business leaders think quite the opposite: In 2014, only 33 percent of business leaders agreed with the statement that "higher-education institutions in this country are graduating students with the skills and competencies that my business needs." More than a third disagreed, with 17 percent saying they strongly disagreed.

"That's really scary," Leaser said. "You've got these parents with this huge college debt and students with degrees that either aren't marketable or are not a good fit for their child. Now there's a resurgence in code schools, community colleges, associate degrees and apprenticeships."

Learning to Get a Job

Today, coding boot camps are a $240 million industry that graduated about 20,000 software developers in 2018. Their popularity rose in part because college graduates found their degrees weren't in demand or that their education was too broad to give them the up-to-date technical skills they needed for many jobs.

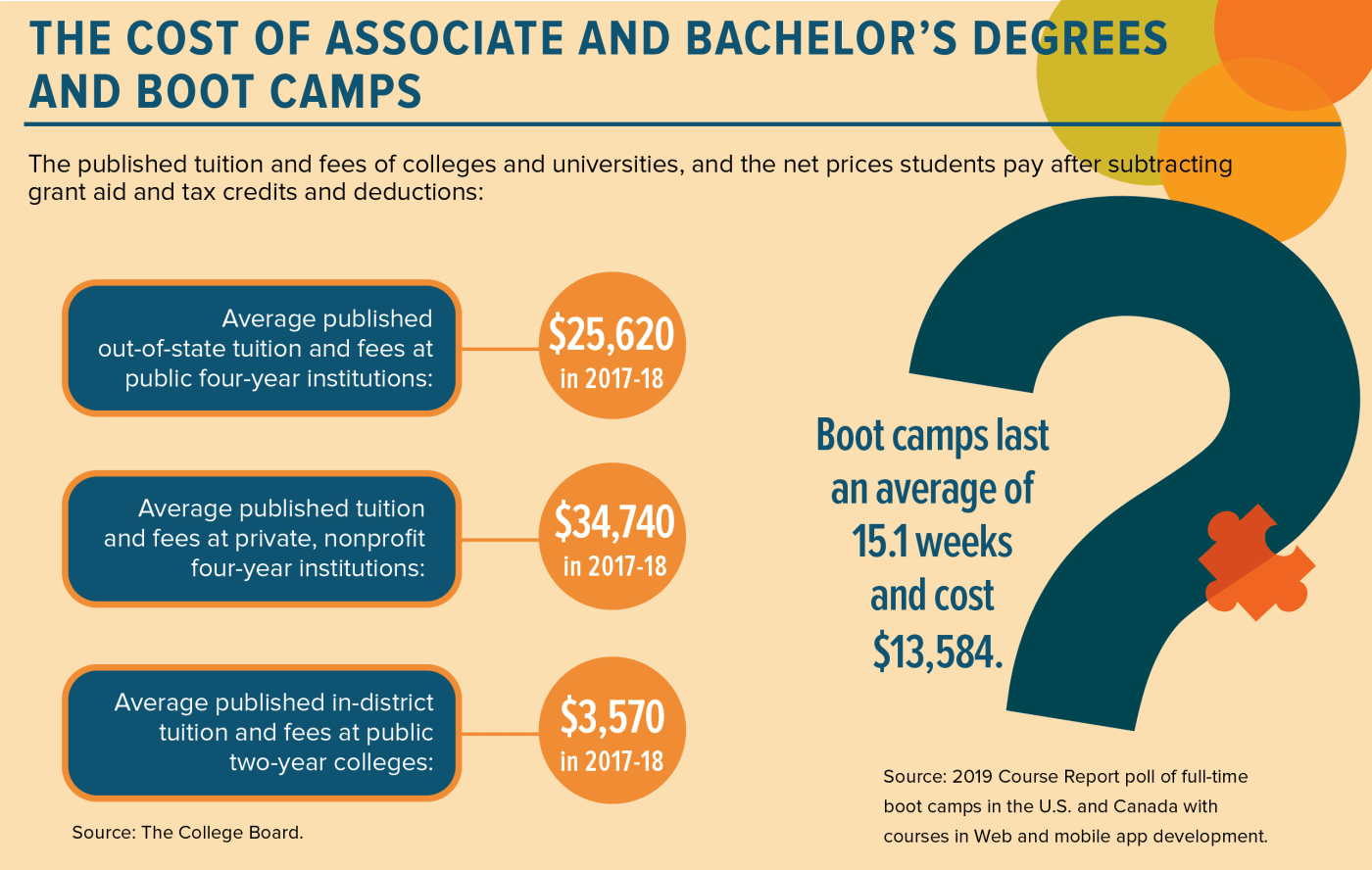

Coding boot camps like Lighthouse Labs focus mostly on Web programming languages, platforms and tools. Tuition can range from $9,000 to $17,000 for a three-month course. Typically, students are between 25 and 35 years old.

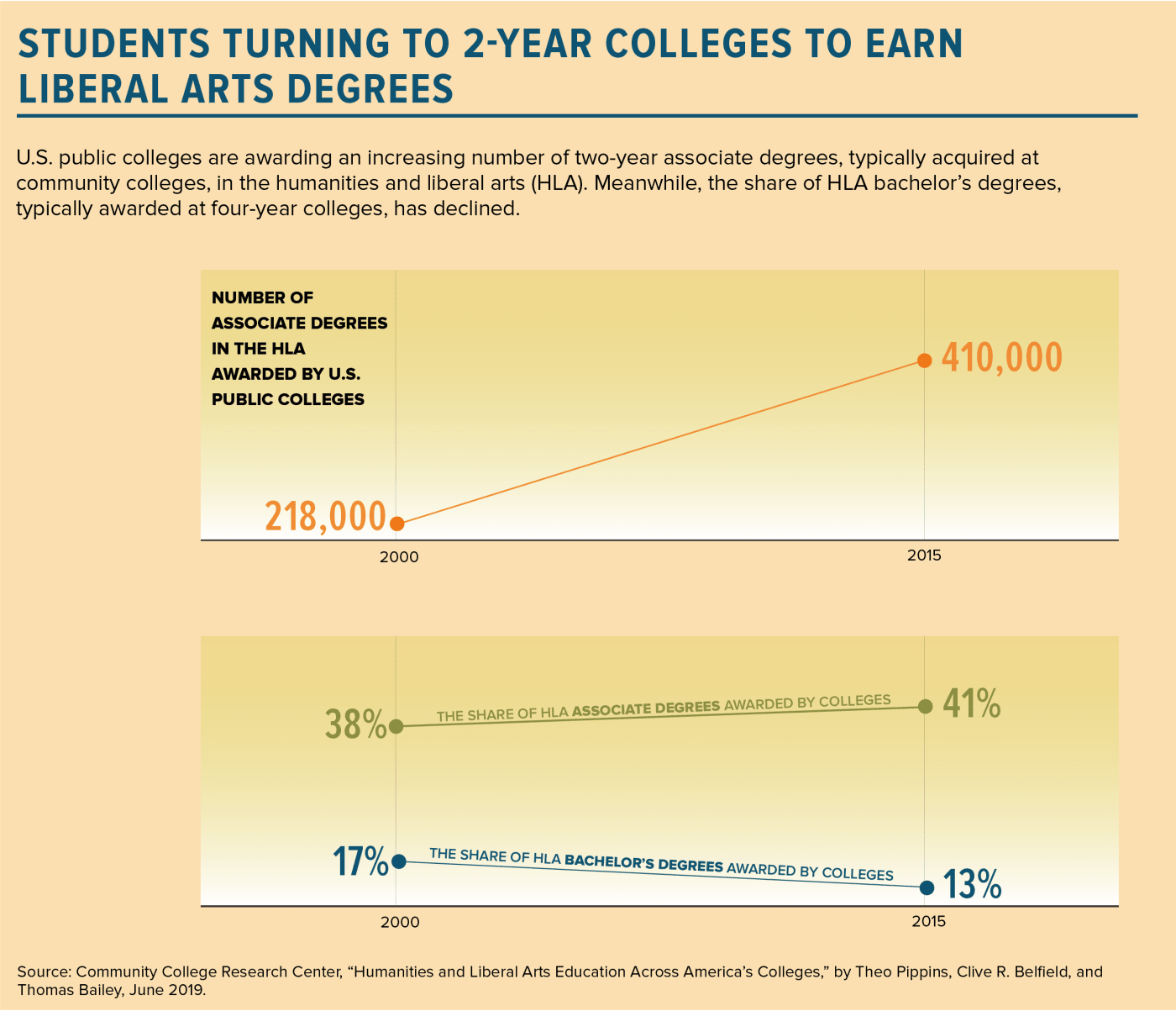

In addition, students are increasingly pursuing associate degrees rather than four-year degrees. The number of associate degrees that community colleges awarded in the humanities and liberal arts nearly doubled between 2000 and 2015, according to a study from the Community College Research Center. Meanwhile, in that same time, the share of four-year bachelor's degrees awarded in the liberal arts declined from 17 percent to 13 percent.

Finally, a shortage of skilled workers in traditional blue-collar occupations has renewed interest in trade schools for industries as varied as carpentry, plumbing, health care and filmmaking. Those schools promise that for a fraction of the cost and time it takes to get a four-year degree, they can help graduates land jobs in industries that pay well. There were roughly 9.6 million students attending trade schools in 1999; in 2014, there were an estimated 16 million, according to the U.S. Department of Education.

"Policymakers, parents, educators and politicians have created this narrative that college is the next step after high school, but that's not necessarily aligned to the [current] economy or to what certain employers need," said Michael Horn, a Yale University graduate and co-author of Choosing College: How to Make Better Learning Decisions Throughout Your Life (Jossey-Bass, 2019). "High-skill jobs require more learning than high school, though it's not clear a college degree is necessary. Employers don't ultimately need the degree; they need aptitude and skills. And there are many ways to gain aptitude and skills."

The Case for College

Lynn Pasquerella is president of the Association of American Colleges & Universities in Washington, D.C. Narrow technical training, she said, isn't sufficient "when rapidly changing technology is rapidly obsolete."

"We have jobs now that didn't exist 10 years ago and jobs 10 years ago that almost don't exist anymore," she said. "How do we prepare students for the work of the future when it's a future that none of us can fully predict? The best thing we can offer students is how to be flexible in the face of change ... and how to grapple with problems for which we don't yet have answers. The thinking is that the people best prepared for that will come from a four-year liberal arts degree."

But colleges are businesses. If the degrees they hand out can't keep pace with an ever-evolving work world, the boot camps, technical schools and other new education models will compete for students' dollars, said Ted Kinney, vice president of research and development at PSI Services, whose assessment tools help companies find and hire workers.

"Sure, going through college may have taught some of the soft skills needed for the job by accident," he said. "But those things could have been acquired in many ways that don't involve college. It really begs the question: When will a college education no longer have a return on investment?"

But Anthony Carnevale, research professor and director of the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, believes that for employers looking for qualified new workers, the four-year bachelor's degree "is still the gold standard."

"But it's a lot more complicated now," he acknowledged. "There are many alternatives. The associate degree may pay off. Specific education like certifications and boot camps may pay off. But the combination of both—the mix of a general education and specific education—that's the combination that wins."