The COVID-19 Retirement Planning Crisis

The economic upheaval unleashed by the pandemic is threatening older workers' retirement savings and security.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a devastating impact on employees' retirement plans. The pain is most acute for those who have lost their jobs and no longer have access to retirement plans such as 401(k)s, which frequently offer automatic deductions and employer matches. But even those who are still employed have been hurt. Many employers have instituted pay cuts that limit workers' ability to contribute to such plans. And in some cases, employers have reduced or eliminated their matching contributions.

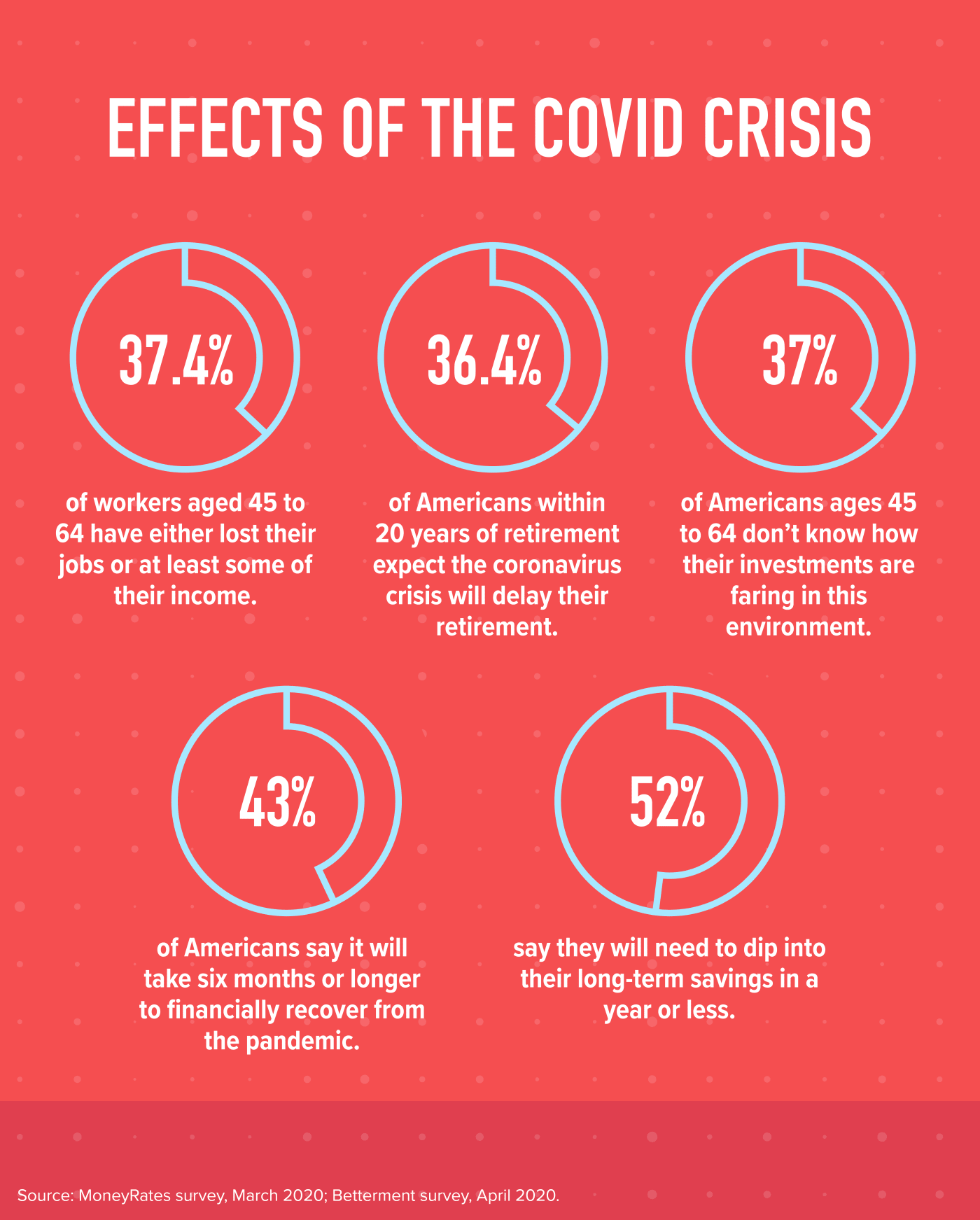

The worsening economic situation means that many employees may be forced to tap into their retirement savings to stay afloat. And while that may provide access to funds now, it could come back to hurt them in their golden years. More than half (52 percent) of respondents said they will need to dip into their long-term savings in a year or less, according to an April survey of 5,000 people by Betterment, a New York City-based financial services company. Forty-three percent said it will take six months or longer to financially recover from the pandemic.

Not surprisingly, many employees also plan to work longer. A MoneyRates survey conducted in March found that 36.4 percent of Americans within 20 years of retirement expect the COVID-19 crisis will delay their retirement.

"There's a misconception that older adults are asset-rich, yet the reality is that the vast majority—80 percent—are financially struggling now or are at risk of falling into economic insecurity as they age," note the authors of a May 2020 issue brief on financial security among U.S. aging adults released by the National Council on Aging and the LeadingAge LTSS Center @UMass Boston. "While the financial situation for older Americans may be difficult today, our analysis suggests things may be getting worse. Ninety percent of older households experienced decreases in income and net value of wealth between 2014 and 2016."

There is some good news. Nearly 72 percent of respondents said they hadn't changed anything about their retirement due to the pandemic, according to a survey of 9,675 adults by Forbes in early May. That includes 79 percent of those age 55 or older. Only 5 percent of employees had changed their asset allocation, and just 3 percent indicated that they intend to take Social Security earlier than planned. In some cases, taking Social Security sooner can reduce the monthly payment amount.

Easing the Penalties

Perhaps the best news is that the federal government in March passed the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, which makes it less onerous for individuals to tap into savings in their retirement plan accounts.

The CARES Act contains the following provisions:

--For employers that permit withdrawals, citizens younger than 59 1/2 with financial hardship related to the pandemic can withdraw up to $100,000 from individual retirement accounts (IRAs) and defined contribution plans without the 10 percent early withdrawal penalty in calendar year 2020. Taxes must still be paid on such withdrawals, but the CARES Act allows payment over a three-year period without being subject to annual retirement plan contribution limits.

--For employers that allow retirement plan loans, the limits were doubled, to the lesser of $100,000 or 100 percent of the participant's vested account balance between March 27, 2020, and Sept. 23, 2020, (180 days following enactment). Generally, loans are limited to the lesser of $50,000 or 50 percent of the participant's vested balance and must be paid back within five years. Individuals with an outstanding loan from their plan with a repayment due between March 27, 2020, and Dec. 31, 2020, can delay their loan repayments for up to one year.

'Plan sponsors are seeking to ensure their employees have the access and the help they need, while also helping participants preserve their 401(k) balances so they can remain on track to achieve their long-term retirement goals. It's a fine balance to strike.'

Dave Stinnett

Companies are not required to adopt the CARES Act's provisions, though a significant majority have chosen to participate and make it easier for employees to access their 401(k) accounts. As of the end of April, among plan sponsors that had made a decision regarding the optional CARES Act provisions, 99 percent had allowed for coronavirus-related distributions and 67 percent had adopted the expanded loan limits, says Dave Stinnett, head of the Vanguard Strategic Retirement Consulting team. His group offers advice on plan design and participant experience to 1,600 plan sponsors in charge of retirement benefits for 5 million retirement plan participants.

"Plan sponsors are seeking to ensure their employees have the access and the help they need, while also helping participants preserve their 401(k) balances so they can remain on track to achieve their long-term retirement goals," Stinnett says. "It's a fine balance to strike. Plan sponsors are taking a very thoughtful approach to their plan design and retirement benefits for participants."

He added that when economic conditions improve, plan sponsors should talk to their clients about getting employees to refocus on meeting their retirement savings goals.

Work in Progress

For now, it appears that many employees aren't taking advantage of the CARES Act's provisions. As of April 30, 2020, only 0.9 percent of participants had initiated a coronavirus-related distribution and less than 0.1 percent of participants had initiated a loan under the act's expanded loan limits, Stinnett says. Those numbers are in line with typical loan and withdrawal volumes for plans for which Vanguard is the recordkeeper, he notes.

But the numbers may well change. "The CARES Act was only recently implemented by many organizations, so the summer will be more telling in terms of any increased volume of loans and withdrawals," says Michael Webb, a vice president at New York City-based retirement plan consultancy Cammack Retirement Group Inc.

Tapping retirement assets now could permanently compromise employees' retirement portfolios later, as many may discover that they lack the ability or the willpower to restore withdrawn funds to their accounts, says Mark Iwry, a nonresident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, a Washington, D.C.-based research group.

Employers should be aware that they have considerable flexibility in how they implement the withdrawal and loan provisions of the CARES Act, Iwry says. Employers may choose to limit withdrawals to levels below $100,000 and loans to less than $100,000 or 100 percent of the participant's vested account balance—unless and until experience makes clear that participants in that plan need the additional access to get by in the current crisis. Such partial relaxation of the limits may be desirable for employers in industries less affected by the pandemic, he notes.

'The SECURE Act is good legislation that should prove helpful in a variety of ways. However, it consisted largely of 'low-hanging fruit'—provisions that generally were not controversial and enjoyed bipartisan support.'

Mark Iwry

"Employers might want to think twice before they offer the full $100,000 of loan or withdrawal options," Iwry says. "Even just offering these options could have a double endorsement effect: Your employer and the government both might be perceived as sending the message that employees can—and should feel free to—withdraw or borrow up to these amounts."

That could lead employees to take substantial withdrawals largely because they like the option to repay within three years without taxation, only to find that they're hard-pressed to amass the liquidity two or three years later to put these savings back into their plans.

"The sense of endorsement or permission could distract many participants from the substantial risk that they're selling low when they withdraw and buying high when they later repay and reinvest the withdrawal," Iwry says.

Strategic Considerations

Iwry says the CARES Act provisions amplify an existing fault of the system that not only allows but also normalizes the notion of full access to one's savings each time one changes jobs, regardless of need or hardship. "401(k)s frame the offer to take one's savings at each job transition whether one needs the money now or not," he says.

Webb says the COVID-19 crisis should lead plan sponsors or consultants to provide, or guide participants to those who can provide, advice on strategic considerations for withdrawals and loans from their retirement accounts.

Employees should be counseled that it usually is beneficial to use other sources of money rather than tap their retirement benefits, Webb says. That's because employees may not be able to replenish withdrawn funds in the future, he explains, or they may default on their loan repayment.

In the past, the tax and financial penalty consequences of premature plan withdrawals have typically been worse for employees than loan provisions, leading plan sponsors to recommend the latter over the former, Webb says.

But he believes the CARES Act may change the analysis. "The loan provisions may be worse than the distribution provision since it allows borrowing of $100,000 or the whole account balance, which is likely borrowing beyond their means for many employees, without extending the repayment terms," he says. "Repayment will start next year, including accrued interest, and there's no guarantee of repayment extensions in future years, unlike this year. Many people will end up defaulting."

Challenging Times

Webb says whether and how an employer should implement the CARES Act provisions depends on how it was affected by the pandemic. "On average, however, we're generally suggesting that all CARES Act provisions be adopted—except for the higher loan limits, which, as currently written, would likely lead to more loan defaults in 2021 and beyond, with terrible financial consequences for employees," Webb says.

This is coming at a time when employers are reducing retirement contributions. A Willis Towers Watson survey found that 12 percent of companies have suspended their 401(k) matches and 23 percent plan to or are considering doing so sometime this year. The suspension was even higher in sectors hit hard by the economic repercussions of the pandemic, such as retail and business services, with more than one-quarter (26 percent) of these companies suspending matching contributions and another 32 percent saying they will do so or are considering doing so this year.

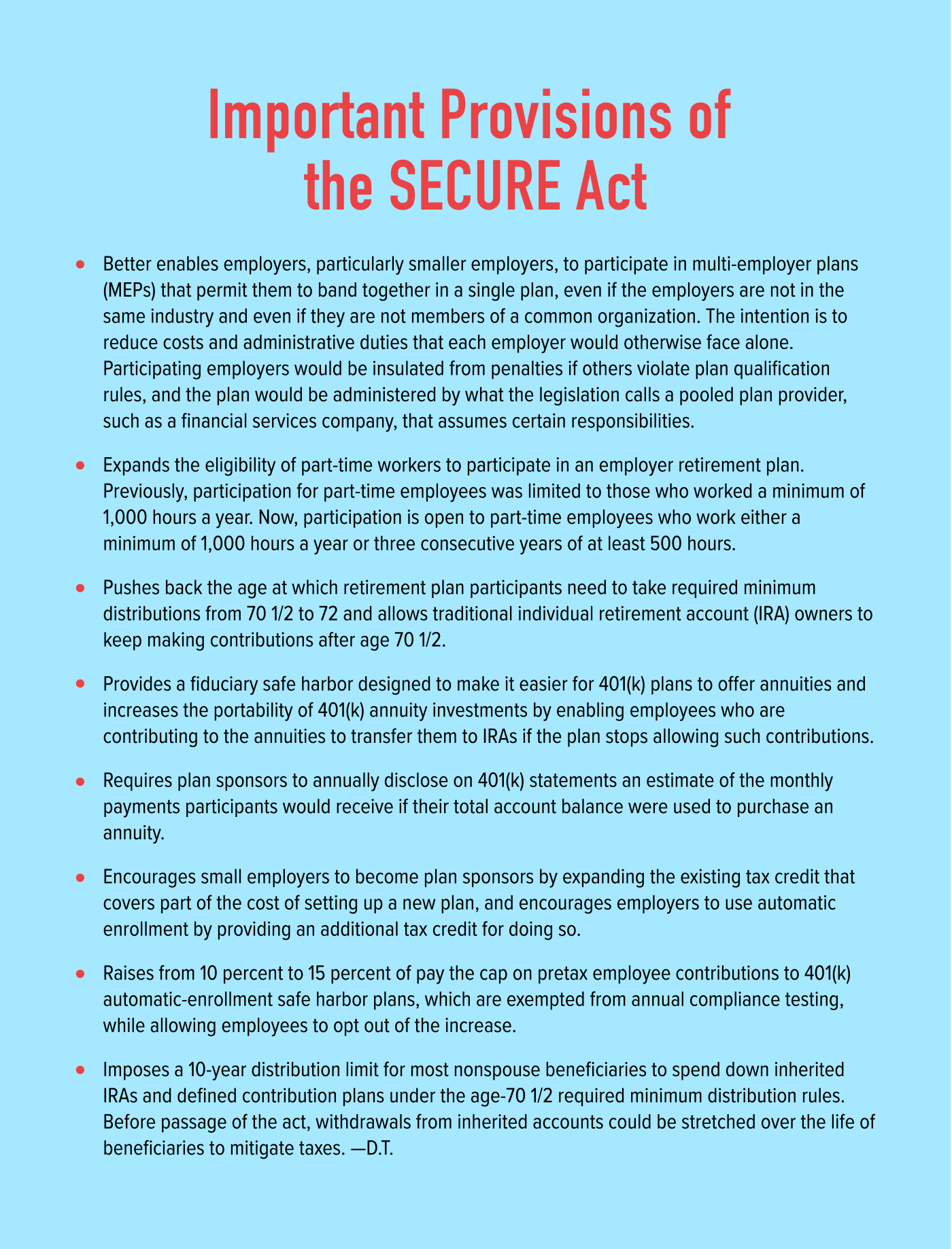

The CARES Act's provisions addressing access to retirement savings complement an earlier federal statute: the Setting Every Community Up for Retirement Enhancement (SECURE) Act of 2019, which went into effect in January. Strongly backed by the Society for Human Resource Management, it was designed to increase access to tax-advantaged retirement investment plans and help prevent older Americans from outliving their savings.

"The SECURE Act is good legislation that should prove helpful in a variety of ways," Iwry says. "However, it consisted largely of 'low-hanging fruit'—provisions that generally were not controversial and enjoyed bipartisan support."

Expanding Coverage

The most important SECURE Act provisions are those that relate to multi-employer plans (MEPs) and those that promote annuities in 401(k) plans.

The "open MEP" provisions could dramatically expand the percentage of smaller organizations that offer defined contribution plans, notes Michael Falk, a partner at investment consultancy Focus Consulting Group in Long Grove, Ill.

Iwry, however, points out that the legislative revenue estimates project only limited participation and that many industry observers likewise expect considerable shifting of employers between existing plans without a dramatic increase in new coverage. He says that the SECURE Act also seeks to expand access to, and functionality of, retirement plans by expanding tax credits for smaller employers that adopt a plan for the first time and offering tax credits for employers that include automatic features in their plans.

Some states, in accordance with a program developed by Iwry starting in the early 2000s, are seeking to expand coverage by facilitating retirement saving by private-sector employees who lack access to employer plans. Oregon, Illinois, California, Connecticut, Maryland and New Jersey have enacted (and the first three have begun implementing) auto-IRA programs under which employers of a certain size must automatically enroll employees into private-sector payroll deduction IRAs facilitated by the state unless they maintain their own retirement plan.. Employees are free to opt out of participation.

Iwry notes that the SECURE Act also aims to expand the availability of annuities offered in conjunction with retirement plans. The law provides a safe harbor that helps protect employers from fiduciary liability in the event that the annuity provider selected ultimately fails to meet its obligation to pay the in-plan annuities.

Also significant, he adds, is a provision that helps clarify for employees how far their savings will go in retirement by requiring that their 401(k) statements provide estimates of the retirement monthly income their account balances would provide if taken as an annuity.

Financial Planning Advice

Despite the crisis, retirement plan design adjustments should never be one-size-fits-all, experts say. "We counsel clients to think about what they're trying to achieve with regard to their retirement plans, their overall benefits and the needs of their workforces," says Amy Reynolds, a partner at international benefits consultancy Mercer.

The conventional wisdom is to not allow short-term events like the COVID-19 crisis to alter long-term planning. Too much focus on the present is a mistake, Falk says. "We all need to look past the present; one to two years of depressed earnings doesn't change [long-term equity values] as much as people think."

On the other hand, Iwry says, the crisis and the downturn in portfolio values may call attention—albeit too late for many—to the need to manage money more carefully in retirement. "Many of us gloss over the structural differences between the financial dynamics of accumulation of wealth versus [spending saved money in retirement]," he says. "It's easy to forget that we're less resilient and more vulnerable to market downturns in [a spending mode] than in an accumulation mode." A steep market decline combined with excessive retirement account withdrawals can leave retirees with a smaller pool of assets that's unlikely to grow sufficiently to recoup market losses, even when the market recovers, Iwry notes.

David Tobenkin is a freelance writer in the greater Washington, D.C., area.