Business Lessons from Abroad

European employment practices help moderate the effects of globalization—for workers, employers and whole communities.

Top executives at Thyssenkrupp, a multinational industrial conglomerate, recently decided to eliminate 6,000 jobs, mostly in the company's home country of Germany. But they weren't able to act quickly. They had to consult with local works councils first and honor layoff-notice periods contained in employment contracts. Strong worker protections in Germany make it difficult to implement major job cuts, with employees typically under contracts that require from one to six months of notice.

In contrast, Kentucky coal miners arrived at work one Monday in July to discover that their employer, Blackjewel, had filed for bankruptcy and their jobs had disappeared. To make matters worse, their paychecks reportedly bounced. The miners, owed back pay, blocked coal trains for weeks in protest.

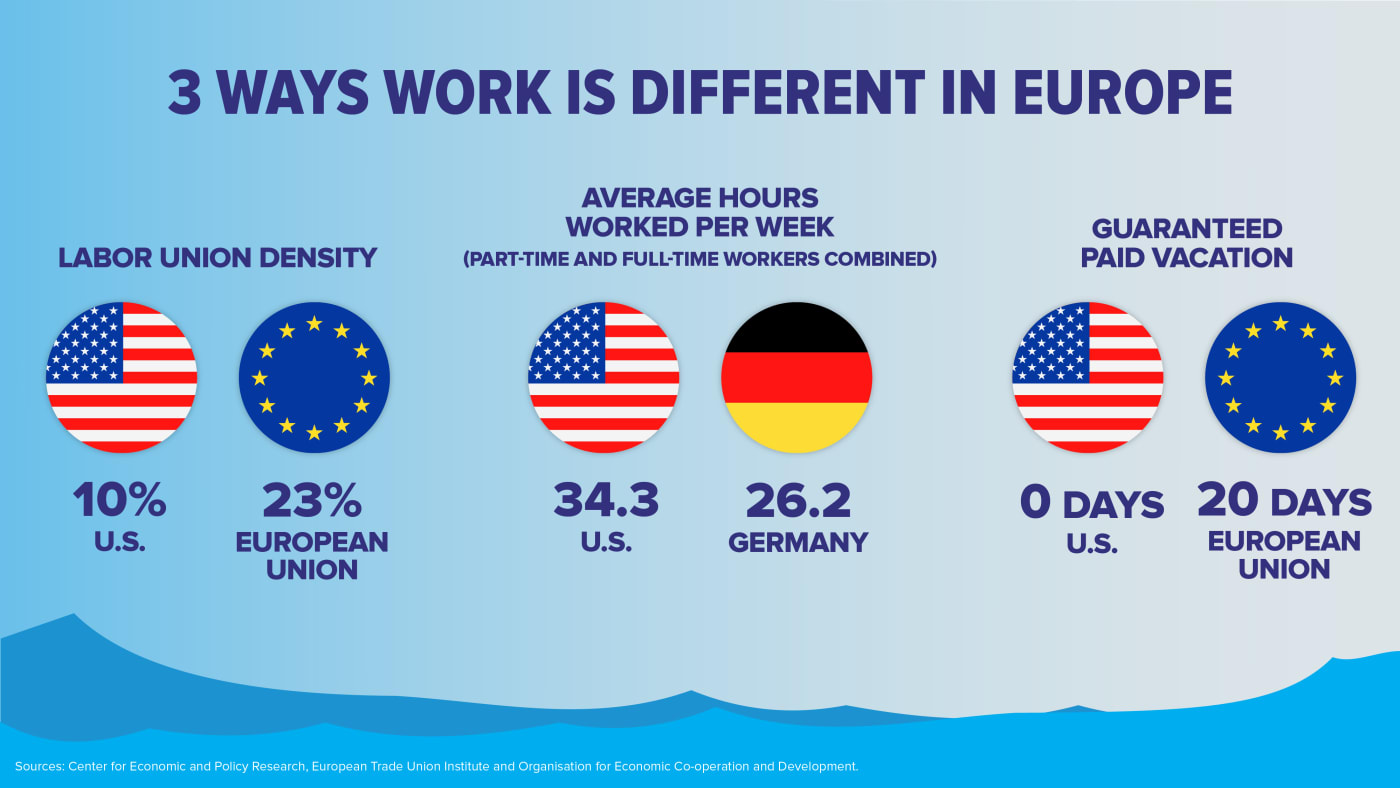

Business practices across Europe differ substantially from U.S. corporate customs. European workers have rights, benefits and job security that are incomprehensible to most U.S. employees and executives. "It's a different mindset," says Lisa Ponder, human resources head, Thyssenkrupp Industrial Solutions, North America, which is located in the Denver area.

And it's a different relationship. "In most EU countries, employees and employers are treated as social partners," says Thomas Kochan, MIT Sloan professor of work and organization studies and co-director of the school's Institute for Work and Employment Research. Throughout Europe, he says, executives and workers believe they must have a partnership in shaping work to succeed.

U.S. executives generally reject this European approach, but they may be warming to aspects of it. Even small U.S. companies have embraced global trading and manufacturing relationships. And when trying to recruit multinational hires, having a clear understanding of the differences in work cultures can be key.

Societies Drive Different Work Models

To be sure, fundamental differences in U.S. and European society drive divergent work models.

"I think it's partly cultural and partly ideological," says Susan Winterberg, fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School's Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, who has studied workplace culture. "Europeans tend to think more about what benefits society as a whole,"

A Pew Research Center poll showed that Americans tend to prioritize individual liberty while most Europeans consider it more important for governments to guarantee that no one is in need.

Still, U.S. executives may be changing their outlook on companies' role in today's society. A rising number of employers large and small have adopted social-responsibility policies addressing environmental, governance and human rights issues, and some have started investing significantly in worker training, which brings them more in line with European thinking.

In most EU countries, employees and employers are treated as partners.

In August, the Business Roundtable, an association of CEOs at leading American companies, announced a new statement defining the "purpose of a corporation," signed by 181 chief executives "who commit to lead their companies for the benefit of all stakeholders―customers, employees, suppliers, communities and shareholders."

With regard to employees, the corporate leaders committed to "compensating them fairly and providing important benefits," and "supporting them through training and education that help develop new skills for a rapidly changing world." Other goals include fostering diversity, inclusion, dignity and respect.

Individual Liberty vs. State Guarantees

Americans value individual liberty without interference from the state, while Europeans value the role of the state in society.

| Country | Prefers state to ensure no one is in need | Prefers freedom to pursue goals without state interference |

|---|---|---|

| U.S. | 35% | 58% |

| UK | 55% | 38% |

| Poland | 56% | 36% |

| Germany | 62% | 36% |

| France | 64% | 36% |

| Spain | 67% | 30% |

Rules Guide Restructurings

Even with leading U.S. executives rethinking corporate responsibility, the U.S. approach differs drastically from European practices.

Layoffs are a prime example. In the U.S., companies typically can let employees go at will. And while the U.S. Workplace Adjustment and Retraining Notification Act requires companies with more than 100 workers to provide 60 days of notice before a mass layoff, employers often fail to do so.

European companies, on the other hand, generally must cite a significant cause for layoffs and might have to pay laid-off workers one or two years' salary plus benefits, says Neal Goodman, president of Global Dynamics Inc., a Florida-based cross-cultural training, coaching and expatriate services firm. Severance pay is often required by law.

The 28 European Union member nations plus Norway have implemented more than 460 restructuring-related regulations that are "explicitly or implicitly linked to anticipating and managing change," according to Eurofound, an EU agency focused on improving living and working conditions.

These rules, which are separate from company-specific programs and collective bargaining agreements, detail member nations' requirements regarding layoff notifications, worker retraining, severance pay, staff consultation on dismissals and other issues.

European labor practices derive to a great degree from national policies and from EU labor standards. Individual countries may exceed EU standards by adopting policies even more favorable to workers.

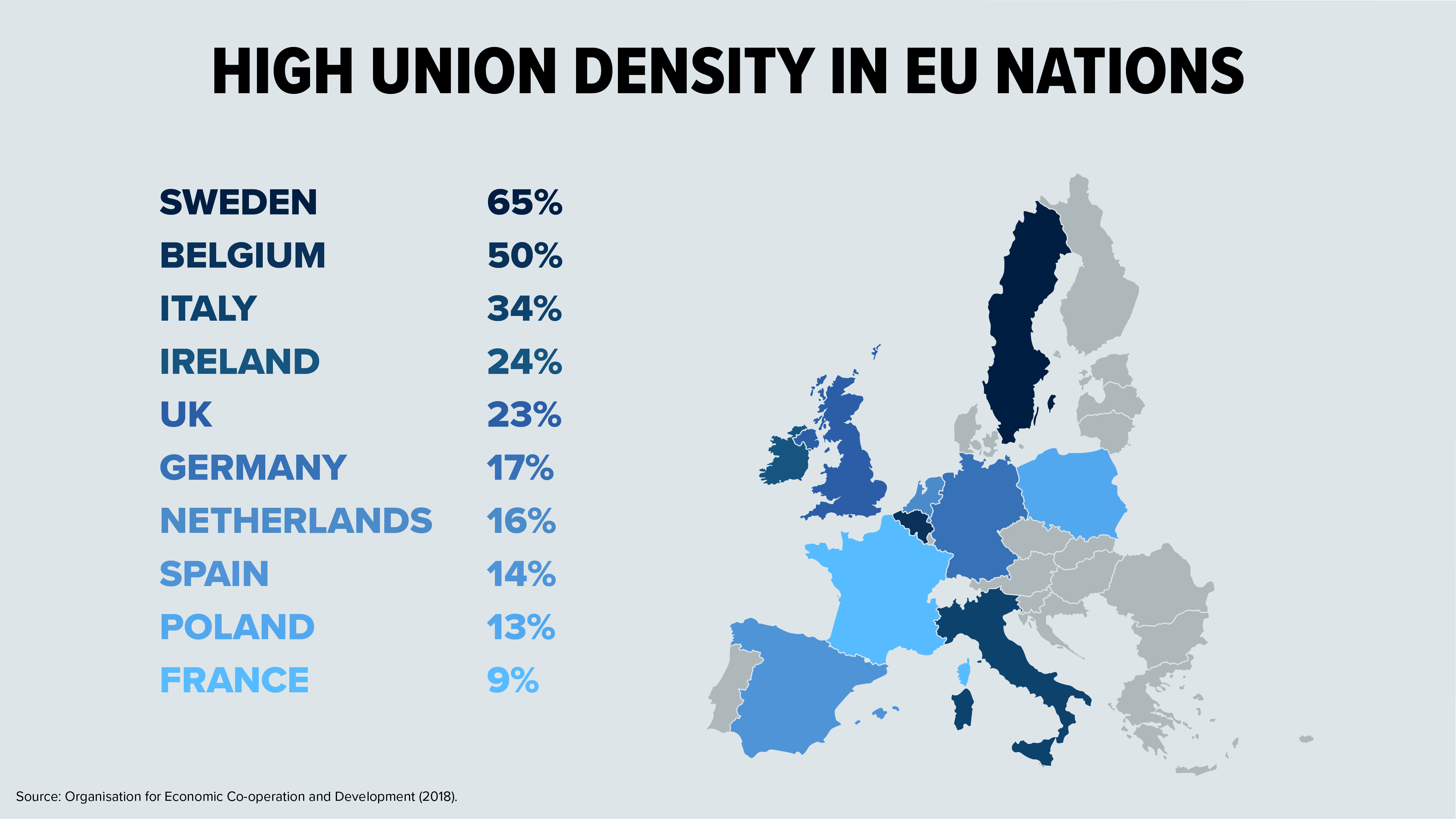

Workers Have a Say

European worker protections are also linked to the significant representation employees exercise through unions and other entities. Worker representation varies across Europe, with unions, works councils or a combination serving workers. Specifics vary by country, but employee-elected councils play a role in a wide range of workplace decisions.

In Germany, companies must work with and receive approval from company works councils made up of employee representatives on decisions affecting wages, terminations, hours and other issues. And employers in EU nations generally must provide for employee participation in health and safety management. At Thyssenkrupp, the council even weighed in on the choice of the company's new computer system, Ponder says. (She doesn't think the concept will work in the U.S., though, as the need to cooperate with such groups "slows every decision down.")

More than a dozen European countries provide for employee board representation in companies reaching certain size thresholds, according to the European Trade Union Institute. Germany's co-determination law allows workers at large companies to elect board representatives. At Thyssenkrupp, employees choose half the company's board members.

There aren't many firms in the U.S. that are prepared for that sort of relationship with workers. And "there's no requirement to engage in that kind of practice," Kochan says.

While European companies may have to consult workers and provide extensive training, compensation and transitional support when laying people off, European businesses and capitalism nonetheless are thriving. Manufacturing is robust, and productivity generally matches that of U.S. companies, Kochan says. "There's no evidence that it's a disadvantage," he says.

European employers, like U.S. companies, have wide latitude to implement layoffs and other adjustments when economic and business conditions change, but often only after collaborating with workers.

"Management learns how to manage in a way that treats other people as respected partners," Kochan says. "That's the difference, and it takes a different approach to management."

European workers have rights, benefits and job security at work that are unfamiliar to most U.S. employees and executives.

Ancillary Benefits

Legal requirements alone, however, aren't the sole reason behind worker-friendly European policies.

"There are also business benefits to treating workers well," says Winterberg, whose research found that European-based companies tend to follow the best corporate practices during global restructurings. "Companies that provide generous support to their workers often did so even when the local laws did not require it," she says.

When Nokia was preparing for a major, multinational restructuring in 2011, the Finnish smartphone giant designed a "bridge" program aimed at helping laid-off employees find new work and supporting communities that depended on the company. The program assisted workers seeking other positions in Nokia, employment with outside firms or new roles as entrepreneurs. It provided training, startup grants, bank loan guarantees and help with resumes.

Nokia wanted to avoid its experience from three years earlier. As Winterberg and a research colleague noted in a report on the bridge program, that's when the company announced an unexpected plant shutdown in Germany, with work to be transferred to Romania, where wages were significantly lower. The 2008 shutdown had prompted bitter protests and consumer boycotts in Germany, one of Nokia's top markets, leading to hundreds of millions of euros in lost sales, the report said.

In 2015, Finland's prime minister appointed a working group to develop a socially responsible model to ease re-employment for people facing layoffs, directing the group to draw on Nokia's bridge program experiences.

The EU itself offers programs and services aimed at softening the effects of globalization and restructuring. The European Globalization Adjustment Fund, for example, funds programs to help workers find new jobs or set up businesses when their employer shuts down a factory, moves work overseas or cuts positions because of a financial crisis.

U.S. Near Top in Hours Worked

Average hours worked per worker (part-time and full-time workers combined), by country.

| Country | Annually | Weekly |

|---|---|---|

| Poland | 1,792 | 34.5 |

| U.S. | 1,786 | 34.3 |

| Ireland | 1,782 | 34.3 |

| Italy | 1,723 | 33.1 |

| Spain | 1,701 | 32.7 |

| UK | 1,538 | 29.6 |

| France | 1,520 | 29.2 |

| Sweden | 1,474 | 28.3 |

| Germany | 1,363 | 26.2 |

Open Leave, Open Minds

Worker rights and benefits in European countries extend to a variety of other areas. In France, for example, employers with at least 50 workers must establish a policy allowing workers to unplug from work technology after hours. A new Spanish law also establishes a right to disconnect. These policies were driven by concerns over employees' stress and a need to respect their personal time and privacy.

Some European laws also give workers on-the-job privacy protections that might surprise Americans. A Spanish court recently ruled, for example, that a company violated an employee's privacy rights when it secured evidence used to dismiss him for spending work time visiting websites featuring betting, sexual content and computer hacking tips.

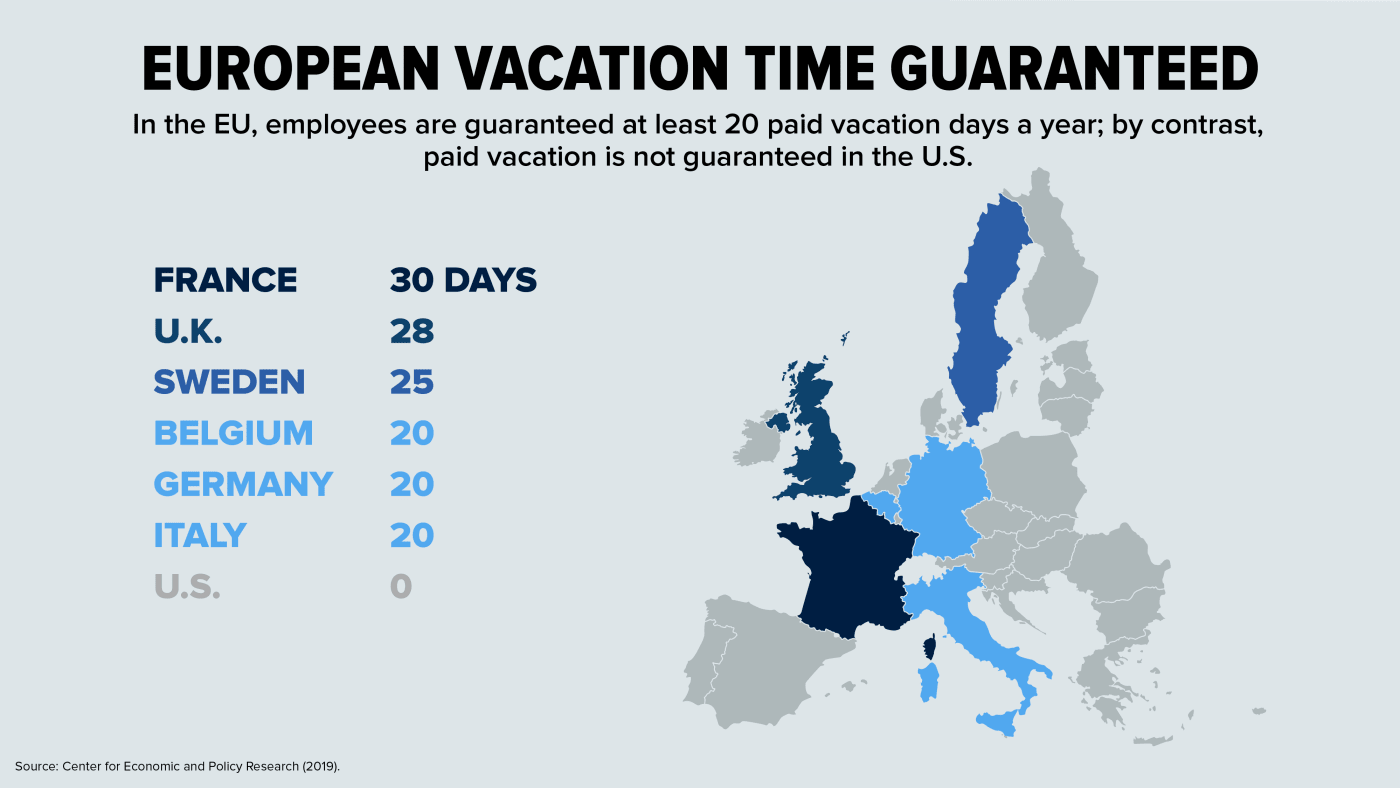

European workers also tend to enjoy lengthy vacations and other generous time-off policies, including paid parental leave that varies by country, sometimes lasting for several months.

When one U.S. company acquired a European manufacturer, it didn't realize that the European business was planning to shut down for the entire month of August, Goodman recounts. The U.S. executives reached an agreement with employees that they could take off three consecutive weeks sometime from mid-June to mid-September, with the time off structured so the facility wouldn't have to stop production.

U.S. employers may need to become more open to generous family leave policies to remain competitive in the global labor market, Ponder says. By the same token, she predicts that Europe may need to trim some of its worker protections to remain competitive with China and the U.S.

While some companies and state and local governments are providing paid parental leave, Kochan notes that the U.S. does not mandate it. "We do need to end the embarrassment of being the only highly developed democracy in the world that doesn't have some form of parental leave on the books as a federal law," he says.

Corporate progress on paid time off and flexibility on working remotely usually applies to the professional and managerial workforce and needs to extend to people on the front lines as well, he adds.

Ideally, employers, rather than government, would drive the change, Ponder says. U.S. firms may adopt more flexible employee policies "as soon as this generation of leaders retires," she says, adding that employers need to be more open to new practices. "That's what the Europeans have on us. They're open to many ideas."

Dinah Wisenberg Brin is a freelance reporter and writer based in Philadelphia.

Explore Further

SHRM provides advice and resources to help employers .

HR Q&A: What Is the European Union?

The EU has established a “single market” that allows people, money, services and goods to move freely within the EU countries.

HR Q&A: Do we have to offer the same benefits to our employees who work in other countries as we do to our employees working in the U.S.?

The short answer is that it depends on the country and how the employer’s benefits plans are written.

3 Steps to Aligning Culture Across the Globe

Aligning culture and strategy across vast distances can bolster business success, but a misalignment can cause headaches and inefficiencies.

What Negotiating Points Are Most Important to European Job Candidates?

When negotiating job offers in their home countries, European candidates prioritize a good salary and a permanent work contract.