Introduction

On June 28, 2017, Steve Lacerda stepped outside San Quentin State Prison in California for the first time in a decade.

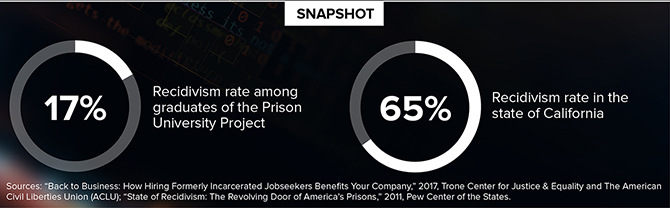

For most ex-cons, leaving prison can be scary and fraught with post-release challenges—including unemployment. That's one reason why over two-thirds of all released inmates will return to prison within three years. But unlike other ex-cons, Lacerda had an advantage: a marketable skill he learned in prison.

He learned to code.

Lacerda participated in The Last Mile (TLM), the first in-prison computer coding program in the United States.

Inmates learn a half-dozen or so programming languages, soft skills and entrepreneurship so they can find and hold down jobs.

The program has been so successful that it has expanded to other prisons across California.

Lacerda and hundreds of inmates have learned to code websites for businesses—giving them a lucrative skill in a market thirsty for talent in a field that generally pays in the six-figure range.

Coding Without the Internet

But it wasn't an easy task—these men had to learn how to code without access to the Internet.

"It was difficult," says Lacerda, who now builds apps as a web developer. "It boggles my mind how we did it in there. Now I run across a problem and I Google it and I have 10 different answers. It was definitely tricky," he said of learning without online access.

"But it made us learn how to program better."

Inmates learn Javascript, Python, CSS, HTML, WordPress and more. By learning entrepreneurship, they can use their coding skills to develop their own companies.

Started by San Francisco-based venture capitalists Chris Redlitz and his wife, Beverly Parenti, TLM began as an entrepreneurship program in San Quentin in 2010. In 2014, they started teaching the inmates to code. Parenti is now the program's executive director.

Inmates "have to qualify to get into the rigorous program," said Parenti, meaning they must be model prisoners who have not committed any infractions. Many have been incarcerated for decades. Some have never even touched a keyboard.

Program participants work on real projects, building WordPress websites and apps for companies."Because they can't use the Internet, the [inmates] work on a closed network and a manager pushes the results to the outside," Redlitz said; inmates can see their work later. "Any money the shop makes is funneled back into the nonprofit."

Nearly 300 inmates have gone through the coding program at San Quentin since 2014, and nearly three dozen people have been released. Like Lacerda, all are in the workforce and none, Redlitz said, have reoffended.

TLM also runs programs in the Folsom Women's Facility, Chuckawalla Valley State Prison, the California Institution for Women and Iron Wood State Prison. Next year it will open at the Pelican Bay State Prison and the Ventura Youth Correctional Facility.

"It's probably the most requested program in the state," Redlitz said. "From the inmates' perspective, it's highly challenging and highly in demand because they realize if they make it into the program, they have a marketable skill."

HR and Working with Inmates

Ex-cons usually struggle to find work, but the program's founders say they haven't had any problems placing former inmates in jobs.

Despite their history, it's not surprising that TLM graduates are a hot commodity: Tech roles are the second hardest-to-fill jobs, according to ManpowerGroup's 2016-2017 Talent Shortage Survey.

Lacerda said he was inundated with job offers once he started looking. "A lot of employers will overlook your background and give you a second chance," he said—especially if you are skilled.

Added Redlitz: "It's about the quality of your work, not your background. The tech industry is the perfect fit for job seekers with unusual resumes."

New Source of Talent?

While 2.3 million people are imprisoned in state correctional facilities in the United States in 2017, 95 percent of them will re-enter their communities, according to a report from the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). A spokeswoman for The Last Mile said that the 5 percent "aren't necessarily serving a life sentence, but sentences may end up being for the rest of their lives." Data for federal prisons was unavailable.

Nearly 75 percent of those who were incarcerated remain unemployed a year after their release, the ACLU reports, adding that more than 640,000 people are released from prison annually.

Seventy million Americans—or 1 in 3 adults—have a criminal record.

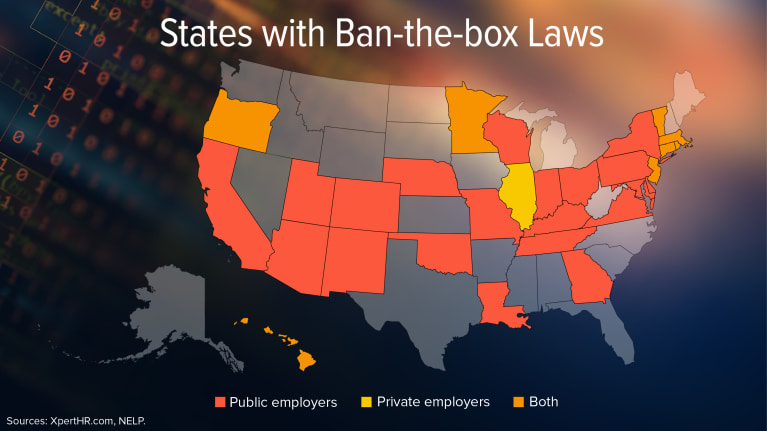

State legislatures are moving to help former criminals find work after they've served their time. Ban-the-box laws that require hiring managers to delay asking about a candidate's criminal history until after an interview has been conducted or a provisional job offer has been extended are proliferating. Currently 24 states and over 150 cities and counties have such laws. Los Angeles in December 2016 became the latest major city to enact a ban-the-box law that applies to private employers.

Applicants will still be screened, however.

SHRM research reveals that 86 percent of employers use criminal background checks on at least some candidates and that 69 percent check all candidates after offering them a job. Thirty-one percent of respondents said an arrest, event without a conviction, would at least be somewhat influential in their hiring decision.

Employers should keep in mind that "these are human beings who are finding ways to be resilient—to transform their lives and to reimagine who they'll be when they come home from prison or jail," said Jasmine Heiss, the former director of coalitions and outreach with the Coalition for Public Safety (CPS), the largest bipartisan national effort to reform the criminal justice system. CPS partnered with TLM, whose inmates designed its website.

Wanted: IT Pros, Criminal Record Notwithstanding

Those affiliated with TLM hope attitudes about hiring inmates will continue to change—especially given the tech industry's staffing shortages.

A fact sheet published by the White House in 2016 revealed that, that year, "there were more than 600,000 technology jobs open across the United States. And by 2018, 51 percent of all STEM [science, technology, engineering and math] jobs are projected to be in the computer-science related fields. The federal government alone needs an additional 10,000 IT and cybersecurity professionals, and the private sector needs many more." By Jan. 30, 2019, the potential shortfall of qualified professionals in the cybersecurity industry is estimated to be 1.5 million.

"This is an area that is in so much demand. I don't think that [being in prison in this field] is so much a barrier" for employers, Lacerda said. "In the technology [industry], these typically tend to be people who are progressive and who are on the cutting edge of things. People just want programmers who are skilled," he said.

Parenti said her goal for the program is "100 percent employment [for participants] and zero percent recidivism."

One step to help achieve that, she said, is for former inmates to take time to reacquaint themselves with society for at least 30 days before they start working.

"I hadn't realized the pace of life out here would affect me so much—it's really fast," Lacerda said, "coming from no movement—no cars, no trains—even the colors [in prison] are limited. It was just a weird feeling." Once he returned to the working world, "being around all the movement and having to work all day and come home" was a difficult adjustment.

A hefty paycheck may make the transition easier. In California, the average annual pay for a web developer is $93,000, according to the job board Indeed.

"It's scary to think about what my life would be like if I hadn't taken this program," Lacerda said. "I don't know what I would have done without this."