Editor's Note: SHRM has partnered with Harvard Business Review to bring you relevant articles on key HR topics and strategies.

Levels of engagement at work are continually low and declining in some parts of the world. Elite consulting jobs have been described as "tedious," "uninspiring," work in which people are told "exactly how to do things." Earlier this year, the Guardian reported that Amazon warehouse workers are treated "worse than robots"—running to fill orders and skipping bathroom breaks as they are monitored by electronic surveillance. Evidence of rising work intensification in many countries has been backed up by the media, including stories about the effect of "greedy jobs" on women, as well as popular books that bemoan demotivating work and that identify the huge toll stressful work has on communities internationally.

We believe that this lack of engagement, burnout and dissatisfaction many employees are experiencing is a result of poorly designed work. Work design refers to the nature and organization of tasks, activities, and responsibilities within a job or work role. From a psychological perspective, when work is well-designed, workers have interesting tasks, autonomy over those tasks, a meaningful degree of social contact with others and a tolerable level of task demands: reasonable workloads, clear responsibilities and manageable emotional pressures.

For employees, the benefits of well-designed work include job satisfaction, engagement, improved home-work balance, lower job stress, better well-being and an overall sense of purpose. For companies, good work design means opportunities to fully harness and cultivate talent by providing more job autonomy, one of the strongest drivers of employee creativity, proactivity and innovation. But when work is poorly designed, the opposite is true. Jobs can become intolerable and demotivating—particularly jobs in which the tasks are repetitive and tightly controlled, or jobs in which the level of demand overwhelms people.

Despite the benefits of well-designed work, poor work design abounds in many companies. Why? The typical answer focuses on macro-level forces such as the decline in unions and inadequate national labor laws. While we agree that large-scale variables are important, our research shows that they do not explain the whole story.

Study #1: Managers Often Make Boring Jobs More Boring

To discover why poor work design continues to be so prominent in organizations around the world, we conducted a study to understand how people think about and develop roles for others. An earlier study shows that, when asked to design jobs, management students at the university level tend to create roles with highly repetitive and boring work due to a belief that such work is more efficient. Our goal was to see if this finding applies to managers and professionals as well.

We invited managers and professionals from human-services industries (organizational psychologists, safety managers, health and safety inspectors) to participate in two online simulations. In the first simulation, participants had to design a job. They were presented with a half-time clerical job made up entirely of photocopying and filing tasks. We then asked them to make it a full-time job by selecting additional tasks from a list and adding them to the current role. Participants could make the job extremely repetitive by adding even more photocopying and filing tasks, or they could make the job more meaningful and interesting by adding tasks such as greeting visitors or helping with a quality improvement project. They were told that all the tasks were relevant, that the clerk was capable of doing them all, and that the job would be a permanent one.

A surprising finding (especially given that we deliberately focused on human service managers and professionals) was that almost half (45%) of the participants designed the job to be even more boring, composed of doing almost entirely photocopying and filing tasks, eight hours a day.

Study #2: Managers Would Often Rather "Fix the Worker" Than Change the Work Design

Next, we asked participants to imagine that they were the manager in various scenarios involving workforce problems. As an example, we told participants they managed a warehouse worker (Karen) who was failing to meet 50% of her deadlines. For each scenario, we made it clear the work design was poor. In Karen's case, we stated that she "moves quickly" and "often runs" to pick up goods, but still can't pick them off the shelves on time. Participants then rated how effective they believed various strategies would be to address these problems. Some strategies focused on 'fixing the poor work design' and some focused on 'fixing the worker'.

Even though quite a few participants chose strategies to fix the poor work design (such as "redesign the work so the tasks don't need to be timed"), a surprising number of participants still opted to 'fix the worker.' For example, despite knowing that Karen often had to run to meet her times, more than two-thirds of participants said they would "send Karen on training"; almost one third chose to "advise Karen to improve her physical fitness"; and nearly one quarter opted to "threaten to reduce Karen's pay if she doesn't improve her times." Each of these strategies indirectly "blames" the worker when poor work design is the more fundamental issue.

How Can Organizations Help?

Managers and professionals are in an excellent position to create meaningful, motivating and stress-free work for their employees. But our research suggests that many will not do so—they have a natural tendency to design poor work for others. Many professionals are also inclined to blame the worker when there are performance issues, rather than change the inadequate work design. Fortunately, organizations can learn from our research, and take steps to improve the situation.

Recognize the importance of well-designed work — from all perspectives. Improving work design from a psychological perspective is not on the radar for many companies. Work design is usually considered from a process perspective only (such as introducing lean principles), or from a physical work space perspective (such as open plan offices). But by ignoring the psychology behind truly good work design, organizations risk disengaging their workers, accelerating turnover and driving down productivity. Indeed, there is little point in having a funky office that is meant to spark innovation, while having bosses who tightly control all aspects of the work.

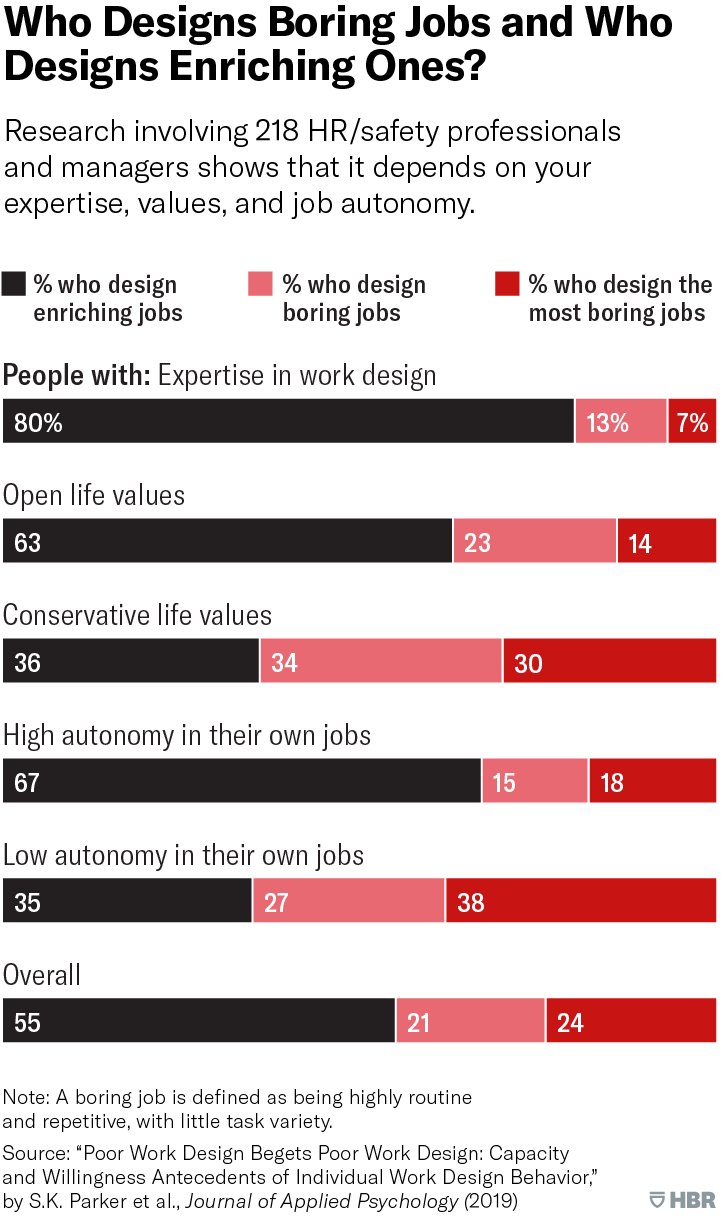

Train managers and other relevant professionals. Leadership teams have an important role to play when it comes to designing quality work. Through their own actions, managers can allow people more autonomy over decisions, ensure that tasks are various, and provide staff with support when demands are high. However, our research shows that these skills don't come naturally for most, even those who work in the human services field. In fact, our findings suggest that people with high conservation life values (that is, those who attach high importance to security, conformity and tradition) value narrow, repetitive work the most, design the worst jobs, and may need additional support and training. Without educating the people responsible for assigning work, poor work design will continue in many work places.

Beware of self-perpetuating cycles. In our study, the worst job designers lacked autonomy in their own careers, suggesting that people unconsciously mimic their work designs when designing work for others. This means that organizations with a hierarchical command-and-control model present a unique challenge for managers looking to shift to a more autonomous model. To avoid a vicious cycle in which bad work is perpetuated, good work design needs to start at the top. Managers who experience the value of well-designed work are more likely to create it for others.

Discuss work design in performance reviews. When a worker behaves in a way that is not ideal (being absent, missing deadlines or failing to innovate), the cause can be poor work design. But our research shows that managers often prefer to 'fix the worker' — sending them off to training programs or removing their bonuses. We believe that including work design in performance review discussions will allow managers to more easily identify how big, or how little, a role it plays in employee performance. For instance, when an employee is not being innovative, rather than assuming the person "isn't up to it or needs training," managers should check to make sure the job has enough autonomy to motivate and inspire creativity.

Involve experts where necessary. Our study found that leaders with specific training and expertise in work design (that is, organizational psychologists) designed more meaningful work. In some cases, particularly those in which improving work design requires a system-level change, a deeper level of expertise is beneficial. Organizational psychology is one of the fastest growing professions in the U.S., with scholars in this field making an increasingly important mark on the business world. We encourage organizations to draw on this form of expertise, and related forms, if poor work design is entrenched in their organization.

Economically and socially, well-designed work pays off. We need to build better work for people, and this need is a timely one. While offering promise and productivity, the digital era also brings with it potential threats to the quality of people's work design. We see this at Amazon, where technology is used to monitor people's movements and to impose excessive control over their actions. In addition, there is vast evidence that well-designed work helps prevent the emergence of mental health issues. Now more than ever, we need a better understanding of which work designs are optimal and how to achieve them.

Sharon K. Parker is an Australian Research Council Laureate Fellow, a Professor of Management at Curtin University in Perth, and Director of the Centre for Transformative Work Design. Daniela Andrei is a Research Fellow at the Centre for Transformative Work Design, Future of Work Institute, Curtin University. And Anja Van den Broeck is an Associate Professor at the Department of Work and Organization Studies, KU Leuven, a research university in Flanders, Belguim.

This article is reprinted from Harvard Business Review with permission. ©2019. All rights reserved.

An organization run by AI is not a futuristic concept. Such technology is already a part of many workplaces and will continue to shape the labor market and HR. Here's how employers and employees can successfully manage generative AI and other AI-powered systems.