What Happened to the Promise of a 4-Year College Degree?

Part 1: College graduates aren't meeting employers'—or their own—expectations at work. Why?

Part 1

Promise of a 4-Year College Degree

Part 2

Students Aren't Learning Soft Skills

Part 3

College Grads Lack Hard Skills, Too

This autumn across the U.S., more than 2 million young men and women packed up their laptops and mattress toppers and headed to college as freshmen, most of them pursuing a promise they've heard practically since infancy—that a four-year university degree will win them well-paid jobs in respectable professions doing what fulfills their passion.

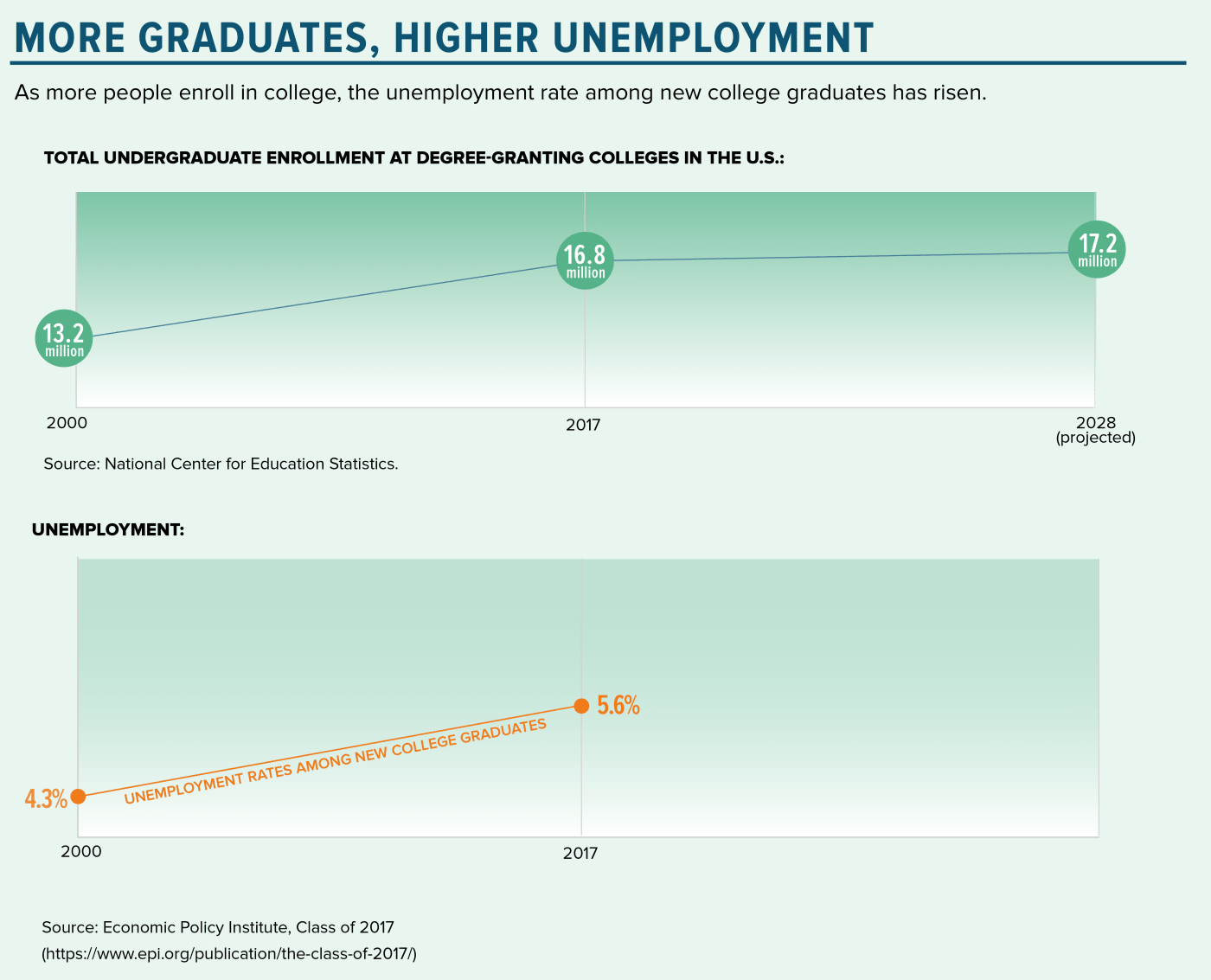

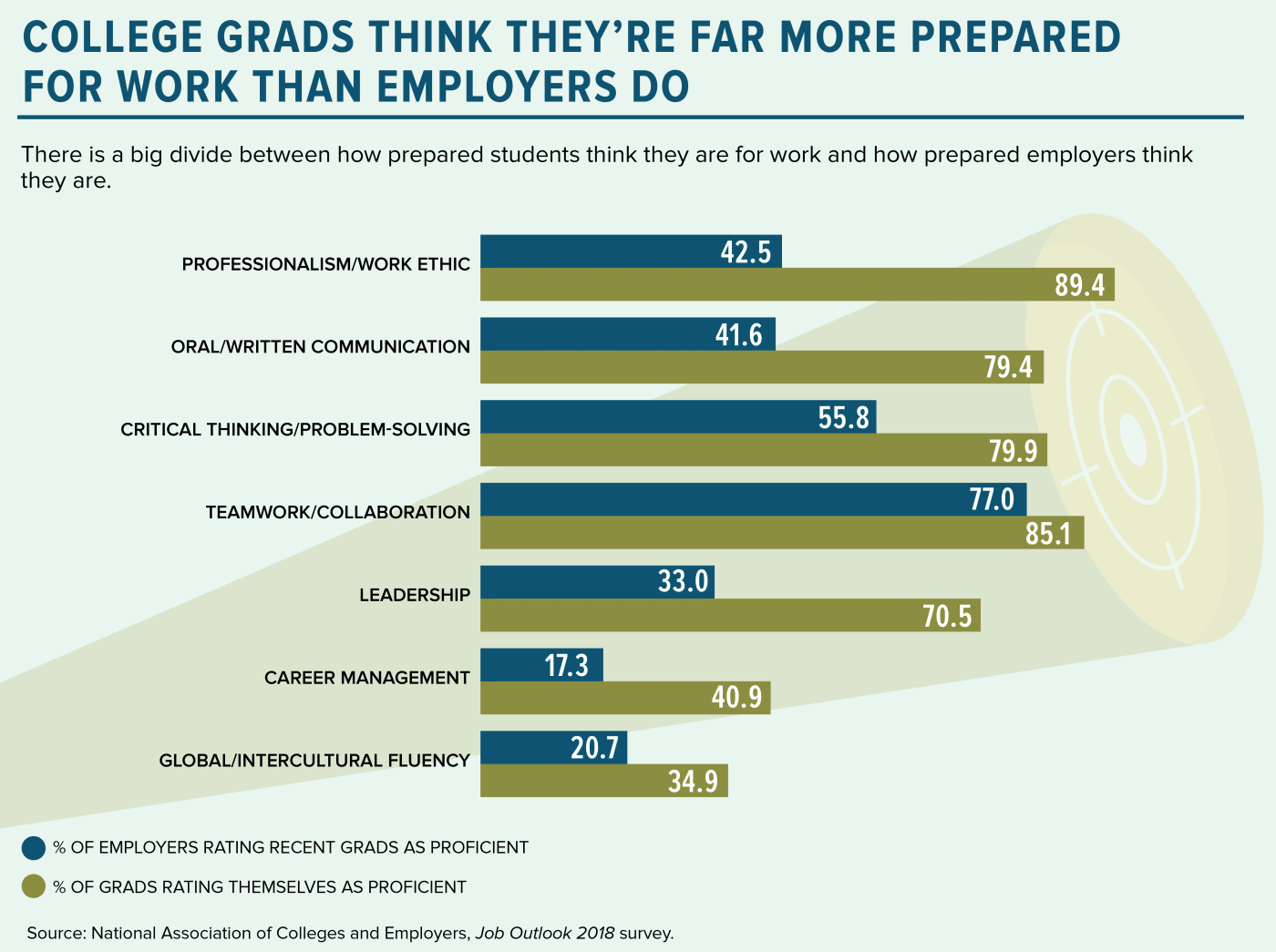

What they may not know is that there is a growing disconnect between what their professors will teach them and what their first employers will expect them to do. And that means many new grads—despite applying themselves academically and graduating with, on average, $38,390 in loan debt—will be unemployed, underemployed or struggling professionally, even if they land a job in their chosen field.

Our five-part series examines college degree holders' readiness for work, what universities are teaching their students and whether employers want too much from the newest workers.

Interviews with nearly 50 college professors and deans, company executives, workplace and education experts, college students and recent graduates point to complex and competing reasons for this disconnect. But on one trend these interviewees agreed: The public conversation about how colleges prepare young adults for work and how well-prepared those graduates actually are has become increasingly heated in an economy where technology advances rapidly and constantly reshapes workplace needs.

Pointing Fingers

Ask Brenda Leadley if most of the college graduates she hires can write clearly, speak persuasively, think critically, work independently and show initiative, and her answer is simple and unequivocal ...

"No."

Leadley's team interviews graduates with degrees in business, finance or economics, mostly for junior underwriter jobs at her commercial insurance company. Leadley expects that college would have taught them these so-called soft skills.

Well, not so much.

"It's pretty surprising to us," said Leadley, senior vice president and head of HR Americas at Allianz Global Corporate & Specialty in New York City. "It's almost like the graduates of today finished only three years of college. They really haven't gotten to where I would expect people were 20 years ago."

Ask Martin Fiore if the college business graduates he hires have mastered Microsoft Excel, a standard tool for collecting, organizing and analyzing data. Nope, says Fiore, who is a tax managing partner for the U.S. Eastern region at EY in New York City.

When businesses don't get what they need from the new college graduates they hire, one of their first punching bags is the college system itself.

"The future of work is arriving faster than the speed of light," said Sue Bhatia, founder of Rose International, a staffing agency based in Chesterfield, Mo. "The educational models of memory-based knowledge accumulation that we rely on are outmoded and will not sufficiently prepare young people for solid careers. We're living in an era of a lag between the old model of college education and the coming future of work. Unfortunately, our young professionals are educated for a world that will not exist as it currently does."

Colleges Push Back

Not so fast, say leaders of the nation's colleges. Earning a bachelor's degree was never meant to prepare students to hit the ground running on day one of a new job, they say. They note that small and midsize companies now invest far less in onboarding and training new hires than they used to. That, they say, is due to an increase in the number of startups and technology-reliant companies where speed and profit are valued above the time and patience it takes to groom a new employee.

Not so fast, say leaders of the nation's colleges. Earning a bachelor's degree was never meant to prepare students to hit the ground running on day one of a new job, they say. They note that small and midsize companies now invest far less in onboarding and training new hires than they used to. That, they say, is due to an increase in the number of startups and technology-reliant companies where speed and profit are valued above the time and patience it takes to groom a new employee.

They also suggest that companies expect a great deal from today's college graduate—far more than was expected in decades past. On the one hand, they say, companies post job descriptions that demand expertise in several computer operating systems, software suites, presentation programs, spreadsheets, and communication and collaboration tools—skills typically mastered in technical schools, not colleges. On the other hand, they want grads with the fine-tuned problem-solving, analytical, writing and speaking skills often mastered in a classic four-year liberal arts program. As the workplace constantly evolves, they say, companies demand employees with the agility to take on roles and responsibilities far beyond their formal training.

"If I'm creating new degree programs around some hot new industry career path, I feel like I'm doing my job because students are going to get right into the workforce," said Martin Van Der Werf, associate director for editorial and postsecondary policy at Georgetown University's Center on Education and the Workforce. "Then I hear back from businesses that the graduates don't have soft skills. There's this constant push and pull: If I push too far on the technical skills side, I'm skimping on the liberal arts side. If I push too far on the liberal arts side, then I'm skimping on the technical skills."

"If I'm creating new degree programs around some hot new industry career path, I feel like I'm doing my job because students are going to get right into the workforce," said Martin Van Der Werf, associate director for editorial and postsecondary policy at Georgetown University's Center on Education and the Workforce. "Then I hear back from businesses that the graduates don't have soft skills. There's this constant push and pull: If I push too far on the technical skills side, I'm skimping on the liberal arts side. If I push too far on the liberal arts side, then I'm skimping on the technical skills."

Nancy Woolever, SHRM-SCP, is vice president for certification operations at the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM). Her team helps businesses connect with colleges so the businesses can advise schools on what they're looking for in a graduate.

"What does a student need to know when they graduate and … come walking through your door to take an entry-level position?" she asks. "The consistent feedback we get [from employers] is at least a three-page list with three columns, single-spaced, everything from A to Z …. Some would hold the opinion that employers are being overly demanding. … The other school of thought would be, 'Yeah, it's a competitive workplace.' "

Moreover, company investment in training new workers appears to be declining. There was a time, decades ago, when business leaders expected that new hires would require a learning curve, so they had managers or colleagues teach new employees on the job. Today's larger companies may have the resources for that type of training, but small and midsize outfits—where much of the job creation occurs—may not. Even if they do, two recent workplace developments—the tendency for younger workers to job hop and the rise of gig workers—may leave employers skittish about investing too much in new hires.

Still, those same businesses seek college graduates who will arrive on day one fully armed with all the skills they need to hit the ground running.

Are businesses expecting too much? Or has a college education changed so much—or not kept up enough with the changing workplace—that a four-year degree is no longer a ticket to a rewarding career and a decent living? As vocational boot camps and online certification programs grow in popularity and produce workers who seem to make businesses happy, is college becoming increasingly irrelevant? Even if it is, will that change the learning choices of millions of young men and women raised to believe that college is not a choice— but an expectation?

Part 2: Students' soft-skills gap.