Incivility Is Running Rampant in the Workplace. How Can Organizations Fix It?

A first step is to measure the scope of the issue. SHRM’s new Civility Index can help.

Over the past few years, tensions around the pandemic, politics, and unrest in many parts of the world have put the concept of civility in the spotlight. As conflicts play out in the workplace, many employers are wondering how to create work cultures conducive to authentic yet civil dialogue.

Step one? Figure out how often uncivil behavior is happening inside and outside the workplace, experts say.

While that may seem like a difficult task, a new tool can reveal some vital answers.

SHRM has launched the Civility Index, which gauges how often people say they have experienced or witnessed uncivil behavior. The index asks respondents to recall the past month and rank a series of statements on a scale from 0 (never) to 10 (almost always). Two sets of statements are shown to each respondent: one in the context of their everyday life (to produce a societal-level score) and one in the context of their workplace (to produce a workplace-level score). Total scores are produced by adding together scores from all items separately for the societal- and workplace-level question sets to produce a societal-level total score and a workplace-level total score. Final Civility Index scores are calculated and placed on a 100-point scale (0 being incivility never occurs, and 100 being incivility almost always occurs) for reporting on the societal-level score and workplace-level score.

The goal of the index, says SHRM Chief Data & Insights Officer Alex Alonso, Ph.D., SHRM-SCP, is to help employers identify how often instances of incivility occur and give company leaders a better understanding of the problem and how it affects their workforce. SHRM Research released in February found that the most common forms of uncivil acts included addressing others disrespectfully (36% observed this behavior), interrupting or silencing others while they were speaking (34%), and excessive monitoring or micromanaging (32%).

“The first step in any kind of fix is an awareness campaign,” Alonso says. “You need to actually measure what the state of civility is within your organization.”

Civility in the workplace is crucial for productivity and employee well-being, he adds. A lack of civility can also cause negative cultural changes and employee turnover.

It crosses pretty much every line and every type of demographic. Ultimately, we don’t see many differences, but that’s kind of the point. This is a shared experience across all types of workers.

Employees who believe their workplace is uncivil are over three times more likely to be dissatisfied with their jobs, the February SHRM survey found. They are also twice as likely to say they will leave their posts over the next 12 months than those who don’t share that opinion. Moreover, employees who say their workplaces are uncivil are 3 times more likely to say they are dissatisfied with their job than those who don’t.

The index is part of SHRM’s latest efforts to encourage employers to address incivility. SHRM is engaging businesses and individuals to be catalysts for civility through its “1 Million Civil Conversations” campaign. Engaging in open and civil dialogue, SHRM leaders attest, can bridge divides and build understanding—not only to create stronger workplaces, but to promote the betterment of society.

‘A Shared Experience’

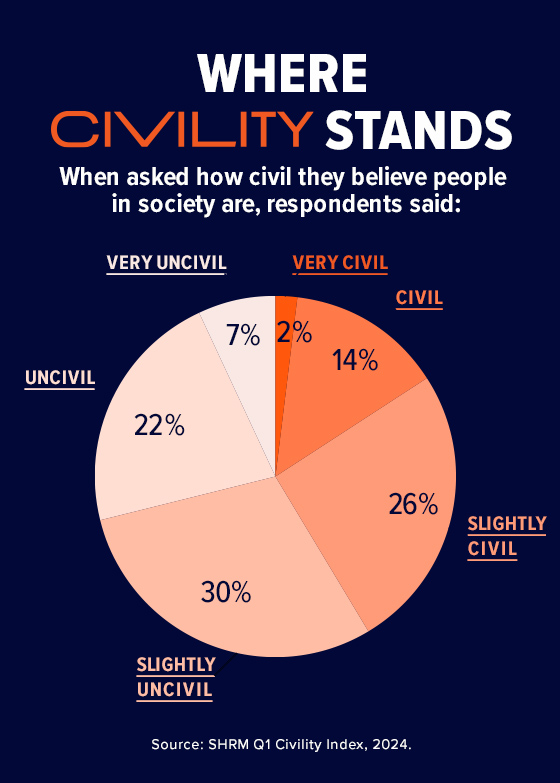

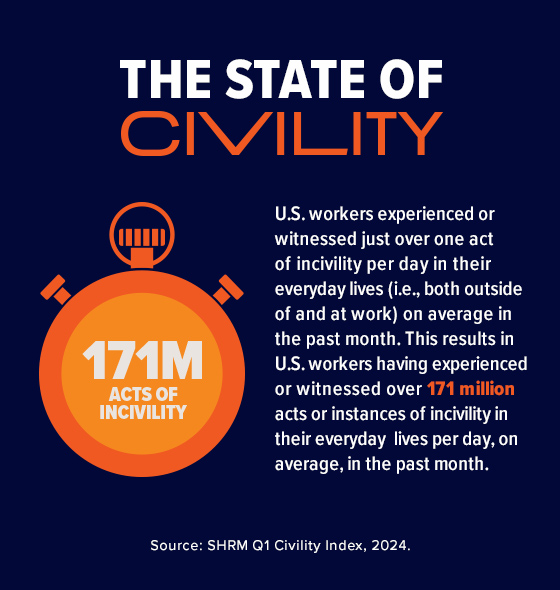

But addressing incivility is no small feat. In fact, incivility is running rampant in the workplace: SHRM’s recently released Q1 Civility Index, which surveyed 1,611 U.S. workers in March, found that the Civility Index score for everyday life (in and out of work) is 42.3 out of 100, while the score for the workplace (while working or while at work) is 37.5.

SHRM estimates that U.S. workers collectively encounter more than 171 million acts or instances of incivility per day—or an estimated 62.8 billion acts of instances of incivility this year. Around 24.7 billion of those will occur in the workplace.

“This is not an acceptable level,” Alonso says. “That’s a precursor for diminished empathy, a bad culture, and a culture that’s going to have turnover, not to mention something that could be potentially criminal and dangerous at some point. The point is, you have to do something to mitigate that. You can’t just let that happen.”

And many observers expect the situation to get worse this year, not better.

The upcoming presidential election will likely exacerbate tensions, potentially compromising civility at work. A third of workers (33%) expect workplace conflicts will worsen in the next 12 months, according to the February SHRM survey. And a 2022 SHRM survey found that 20% of employees said they had been mistreated by their co-workers or peers due to their political views.

Complicating the matter is that employees don’t always share the same idea of what constitutes respectful interactions, with different generations often holding contrasting views. Younger employees’ desire for transparency and openness to discussions about personal issues can make older workers uncomfortable. In addition, mature workers are sometimes frustrated by what they say is younger professionals’ tendency to take constructive criticism as a personal affront.

“If you ask 30 people to define professionalism, you will get 30 different answers,” says Kate Zabriskie, owner of Business Training Works, a Port Tobacco, Md.-based soft-skills and etiquette course provider. She says the rise of social and specialized media has weakened the country’s shared experience.

“You really can live in your own ecosystem,” Zabriskie adds. “I think some of these things that we used to take as givens aren’t anymore.”

SHRM Senior Researcher Derrick Scheetz, the study’s lead, says that because people have different views of what exactly civility is, or what incivility is, SHRM decided to capture a range of behaviors in the Civility Index, rather than singularly define the concept of incivility.

“We want it to capture the wide range of civility and incivility,” he says, adding it’s important that workers can define for themselves when they have experienced what they consider a problem at work.

“Something may be very offensive to one person, but somebody else may not even notice it, so two people can see something in a very different way,” Scheetz says. “It’s important to note that things matter differently to different people.”

While a politically charged screaming match in the office may certainly be construed by most as uncivil, not everyone will consider someone talking over another colleague as being uncivil.

For his part, Scheetz says he would “equate incivility to any behavior that issues a degree of disrespect.”

One thing the Civility Index already proves is that incivility is happening across an array of different industries, and among all types of workers.

“It’s occurring everywhere,” Scheetz says. “If you work in person, obviously, you can’t escape it. But we’re finding remote workers are also experiencing incivility. It crosses pretty much every line and every type of demographic. Ultimately, we don’t see many differences, but that’s kind of the point. This is a shared experience across all types of workers.”

Fostering Civility

In addition to measuring civility—and incivility—to get an idea of how workers are affected, employers can deploy a number of tactics to create more harmonious workplaces. Conflict management seminars, team-building exercises, and etiquette training all are part of employers’ toolboxes. Nearly half (45%) of companies offer employees etiquette classes, and another 18% have such classes slated to start this year, according to a 2023 study of 1,500 business leaders by Resume Builder, a Seattle-based provider of resources for job seekers. Two-thirds of companies offering the classes deemed them a success. Topics typically covered in the classes include conversing politely, dressing professionally, and taking constructive criticism.

One thing I encourage people to do is to practice being civil with one another and having other people observe them as they do this.

One way to avoid uncivil behavior in the workplace is to encourage conversations that don’t necessarily have anything to do with work, says Loralyn Mears, founder and CEO of STEERus, a River Vale, N.J.-based workforce training company. Organizations should organize informal functions such as lunches where people just chat and learn more about one another, she says.

“People keep their earbuds in while they are waiting in line for coffee. They don’t talk to anybody else waiting in line,” Mears notes. “There’s no sense of belonging and unification.”

Mears says that if people develop a sense of community and friendship with their colleagues, they will be more likely to treat them courteously and civilly.

“It’s a lot harder to be polarized with somebody you actually like and care about,” says Kendra Prospero, founder and CEO of Turning the Corner, a Boulder, Colo.-based HR consulting firm. “You may not agree with them, but you’re more likely to not be toxic about it.”

Creating such bonds may be more challenging in a hybrid or remote setting, though it is possible. Prospero’s company has been fully remote since the pandemic, and she continues to explore ways to foster bonds. Each weekly meeting starts with celebrating colleagues’ personal or business successes. In addition, the firm’s 20 employees gather monthly for a virtual team-building exercise.

Alonso says practicing civil conversations is also key.

“The thing I encourage almost everybody to do is actually practice having civil conversations,” he says. “People don’t get as much exposure to civility as we think they do. It just doesn’t happen that way. One thing I encourage people to do is to practice being civil with one another and having other people observe them as they do this.”

Sometimes the most important thing that comes out of such conversations is a better understanding of the influences and situations that people have experienced that have led them to their own perspectives and beliefs. And often the most civil result is agreeing to disagree, Alonso says.

‘Time to Take Action’

The bottom line, Scheetz says, is that if employers look at the data and pay attention to the signs, they will realize that incivility is a big problem in the workplace.

“It’s time to take action, and it’s time to understand that these things are happening,” he said.

Currently, as SHRM’s Civility Index shows, incivility isn’t occurring to a point that is “completely detrimental for everybody across the board, but it is at a point that should not make people feel very comfortable, and that includes businesses,” Scheetz notes.

He warns that if employers fail to act now, the problem will only get worse, resulting in more employee turnover, lost productivity, and lowered employee engagement.

“Once these uncivil acts occur, once people have taken these things personally, once they have ultimately affected their employee experience, it’s probably too late,” Scheetz says. “And it’s going to be very hard to turn things around at that point.”

By Kathryn Mayer and Theresa Agovino