Rethinking the Open Office for an Agile Workplace

Agile' designs gain favor in the quest to optimize space.

Opening the Door to Modern Workspaces

It took 23 years for Peter Hirst to earn a coveted workplace status symbol: a corner office with a view. He enjoyed the gravitas that the office conveyed and the space it provided.

But Hirst gave up his office last year and now shares a large open room with roughly 35 colleagues. His belongings, amassed over a 35-year career in education, are stuffed into a locker that's about the same size as the one he had in high school.

Hirst wasn't demoted. He and his team, who develop executive education programs for MIT's Sloan School of Management, opted to work in a space without offices, walls or assigned seats. Employees move around with their laptops, settling in to whatever area they find most conducive to their task.

One section is designated for quiet work, while another is earmarked for soft conversations. A third is allocated for louder group discussions.

A communal cabinet provides a place for people to display the trinkets that once decorated their desks, though some of the staff carry their mementos with them as they switch spots.

The layout stimulates energy and cooperation among employees, Hirst says. That was missing from the group's former workspace—a maze of high-walled cubicles.

"It's been a great thing," says Hirst, senior associate dean in the Cambridge, Mass., management school. "I tell everyone I meet about it. Now I'm an evangelist."

The concept is often called "hoteling" or "activity-based seating," though definitions and lingo vary. Similarly, "hot desking" allows employees to migrate to open computers and workstations. These are part of the "flexible" or "agile" approach to office design that's becoming more popular in employers' never-ending quest to increase productivity and collaboration while occupying as little costly real estate as possible to keep real estate costs down.

But finding the right balance between privacy and productivity has become a serious challenge.

"The pendulum is in the process of swinging back from offices that don’t have any kind of partitions. We used to think about how to make spaces efficient then it became about how to make them more effective. Now it is how do you create spaces where people want to be," Janet Pogue McLaurin, workplace leader of Gensler, a New York City-based architecture and design firm.

Roughly 20 years ago, companies began eliminating the soul-sucking cubicle farms that occupied the center of their workspaces and were flanked by private offices lining the walls. A desire to mimic the blueprint favored by tech firms pushed company leaders in various industries to build offices with practically no barriers between staffers, believing that the arrangement would spark bonds among colleagues and yield copious great ideas. Instead, studies found that such designs inhibit communication, increase sick days and frustrate employees.

Those realizations have led decision-makers to reconsider the wisdom of open floor plans.

"We used to think about how to make spaces efficient, then it became about how to make them more effective. Now it's: How do you create spaces where people want to be?"

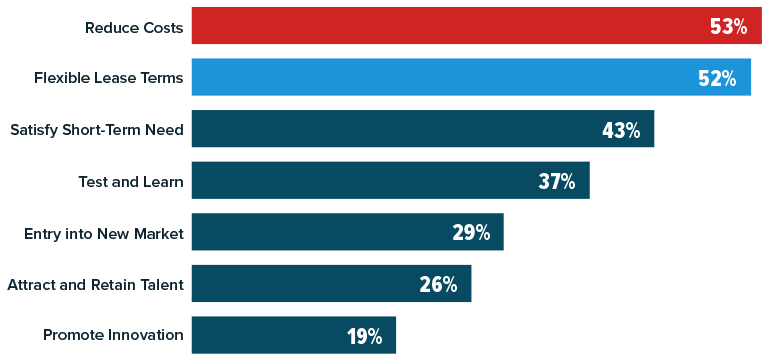

Driving Your Decisions to Utilize Flexibile Office Space Solutions

Source: America’s Occupier Survey, 2018 by CBRE Inc.

Evaluating Open Office Outcomes

Roughly 70 percent of offices have some sort of open floor plan, experts say. The more recent designs include rooms for individual or group work, as well as various types of noise control. Workplaces with fewer assigned seats are also becoming more common.

| 25% of companies have some type of unassigned seating, and the amount was expected to grow to 52% in the next three years.

|

New York City-based design firm Ted Moudis Associates reported last year that 24 percent of its clients' employees have unassigned seating, up from 18 percent in 2016.

Rising commercial rents across the country have fueled the drive to make better use of office space. Employers have had some success reducing costs with open offices, but attempts to spark productivity with such designs have faltered, according to a wide range of research.

Migrating to agile or flexible designs also presents issues and similarly receives mixed reviews from employees.

Slightly more than half of 1,000 individuals surveyed (54 percent) said they believed hot-desking created a welcoming environment, according to Verdict.co.uk, a British news site. Yet in analyzing data provided by Workthere, an office space provider, the news team found that only 46 percent thought the setup increased their productivity.

Workers overall say they're less effective in activity-based seating, according to a study by Leesman, a London-based employee research firm. A certain segment of people blossoms in that situation, however—most notably those who change their location during the day.

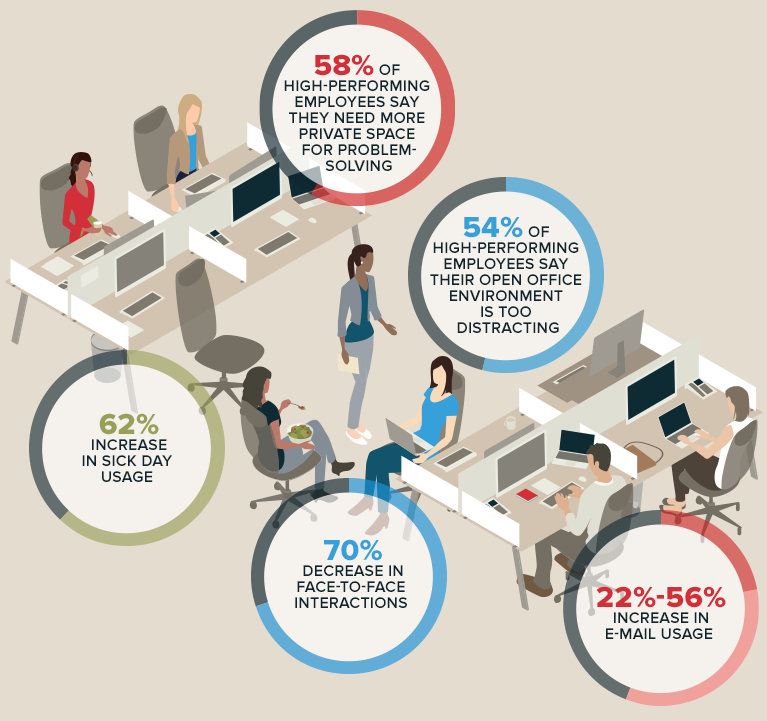

The Case for Workspace Privacy

Unintended byproducts of open office floor plans

Sources: Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B; Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment and Health, 2011; survey by software strategist William Belken.

"You want a work environment that gives people choice," says Jamie Feuerborn, director of Workplace Strategy at Ted Moudis.

One reason open floor plans can be so poorly received is because companies build them before examining how people in the organization communicate and collaborate, she says. An effective office design carefully considers those dynamics and allows for different designs for different teams.

For example, Ted Moudis works with banks and law firms that have very traditional offices for senior executives, while the floors where staffers work on tech projects feature activity-based seating in a much more casual setting.

"All kinds of companies compete for tech talent these days," Feuerborn says. "You want to keep them happy."

Success Stories in Open Office Design

Executives at Saint-Gobain North America opted to stick with an open floor plan when they moved the company's 800 employees three years ago, though they were careful to improve upon their previous space.

The design for the new building allows for better air quality, heating, cooling and lighting than the former headquarters. The new cubicles have lower partitions and wider openings.

One issue was paramount: acoustics.

"If you get acoustics wrong, the whole design won't work," says Lucas Hamilton, manager of building science applications at Saint-Gobain North America, the Malvern, Pa.-based division of the French construction supplies manufacturer. "It's a real dance to try to find the right combination of materials to use, and it takes a lot of research."

Among the most expensive design elements in the company's 277,000-square-foot space are the LEED-certified building ceiling tiles. The materials on the ceilings, floors and walls were all chosen for maximum noise absorption. White noise is also piped into the office, which helps create an aura of quiet.

There are very low partitions between employees' desks, though most people choose to have them extended upward, with laminated glass panels to muffle sound. The glass also has the benefit of allowing sunlight into the middle of the room. There's one huddle room for every eight workers, though Hamilton says the company doesn't need that many.

In the first three weeks at the new office, sales leads generated by the call center increased 140 percent. The improved acoustics made it easier for the workers to hear clients, an internal study concluded. Better access to sunlight also improved their moods.

"They're having deeper conversations with the people who call in," Hamilton says.

And because the call center's desks are arranged to allow for easier conversations among employees, workers can bounce ideas off one another about how to better help customers, he adds.

Atrium Staffing in New York City moved its 100 workers to a new open space last year. The organization's executives still sit in offices—albeit glass-walled ones.

"The whole concept is transparency and inclusion instead of recognizing status," says Cara Zibbell, director of human resources at Atrium.

The design improves productivity, she says. "It creates a healthy, competitive environment. If I see someone next to me on the phone getting a new client or placing one, it motivates me to do the same. People feed off each other's energy."

At Retail Design Collaborative, productivity has fallen slightly since the architecture firm's 130 employees moved into an open office space in the fall of 2016, according to Sean Slater, a principal at the Long Branch, Calif.-based company. But Slater can't pinpoint the reason for the drop-off.

Noise doesn't seem to be the culprit, as most people in the office speak softly for fear of disturbing their colleagues. In fact, Slater speculates that uber-politeness may be to blame because workers lose a lot of time ducking into meeting rooms, even for short conversations.

The firm's leaders aren't even considering reverting to individual offices, though. "This way, it's more democratic," he says. "When you have an office, there's a tendency to close the door."

Different departments have different needs regarding noise levels and space, so the firm is shifting teams around in the building, hoping to find the best fit. Slater adds that while the productivity dip remains perplexing, at least the company is saving money on rent. The firm's current space is 3,000 square feet smaller than its former headquarters.

"On balance, I think openness is better," he says. "There's more communication, and from an economic point of view, it's cheaper."