Bridging the Gender Divide

White men continue to dominate corporate America's hierarchy, but some companies are making efforts to change the landscape.

After nearly two years of being denied prime assignments, subjected to coarse humor, and undermined and disrespected by male colleagues in the Information Services and Technology department of UC-Berkeley, Vanessa Kaskiris had had enough.

She filed a complaint with the university, and six months later investigators issued a report. While it dismissed several of Kaskiris' claims, the report concluded that two of her co-workers had created a gender-based hostile work environment. A few days after receiving the news in September 2016, Kaskiris met with the department manager and was told that her position was being eliminated due to budget cuts.

"I thought we were discussing the finding," recalls Kaskiris, who now works elsewhere at Berkeley. Last year, she went public with her story because she didn't believe that the leadership at her former department was moving to change the dynamics that had caused her so much pain. Her disclosure triggered such an uproar among the staff that the department was forced to hire an outside consultant to study the culture.

"I waited. I was patient," Kaskiris says. "It was difficult to go public, but I realized my silence was only protecting them."

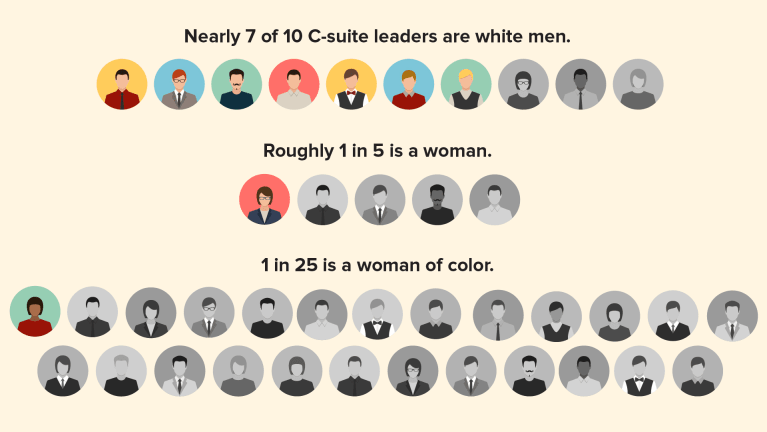

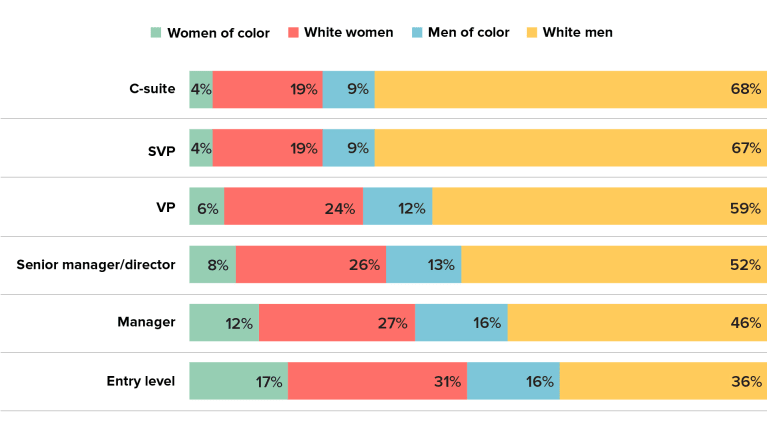

Stories like Kaskiris' are becoming all too familiar in the era of #MeToo. What's also too familiar is how indifferent men can be to the struggles of women and minorities in the workforce. White men hold 68 percent of C-suite positions, compared with 19 percent for white women and 9 percent for men of color, according to the Women in the Workplace 2018 report by LeanIn.Org, a nonprofit group dedicated to fighting workplace gender bias, and consulting firm McKinsey & Co. Women of color hold just 4 percent of those posts. The figures are flat compared with 2017 numbers.

Berkeley's IT department tapped Catherine Mattice Zunell, president of Civility Partners, to improve the atmosphere. The pushback she encountered early on illustrates why creating a diverse workplace is so difficult, despite the billions of dollars that institutions spend on such initiatives.

Few men volunteered to sit on an employee counsel that Mattice Zunell was assembling to work with management on improving the environment. Only two of its 11 members are male. One man refused to acknowledge that he played a role in creating the unpleasant atmosphere.

"Some men don't understand," Mattice Zunell says. "Their experience was fine and dandy."

These men don't realize how their actions can create a toxic brew—a blind spot especially prevalent in male-heavy industries such as tech. But even in firms that don't resemble a "Game of Thrones"-like environment, there aren't enough white men dedicated to populating the workplace with those that don't look like them. Only 51 percent of white men say they're committed to diversity, according to the 2018 report. While that's an improvement from 47 percent in 2017, not every signal is positive.

Sixty percent of male managers say that they're uncomfortable mentoring, working alone with or socializing with female colleagues, according to a recent national survey of U.S. adults by SurveyMonkey and LeanIn.Org. That's an increase of 14 percentage points from last year's poll.

Men's actions—particularly white men's actions—are under a microscope. This fall, the University of Kansas is offering "Angry White Male Studies," a class that will examine why white men have become bitter and how their attitudes have been affected by the rights-based movements of women, people of color and LGBTQ individuals. Earlier this year, Why Do So Many Incompetent Men Become Leaders? (And How to Fix It) (Harvard Business Review, 2019) hit bookstores, along with an updated version of last year's best-seller Brotopia: Breaking up the Boys' Club of Silicon Valley (Portfolio, 2018), which chronicles rampant chauvinism in the tech industry. Earlier this year, razor-maker Gillette aired a highly controversial campaign during the Super Bowl depicting men engaging in sexist behavior that encouraged them to be better.

"There's never been a worse time to be a man," says Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic, author of the book on incompetent men. "They perceive that their power and authority is being threatened."

Women Remain Underrepresented in the C-Suite

Establishing Male Allies

Diversity advocates typically want to recruit white men as allies, so there's value in not alienating them or putting them on the defensive.

"Men hold the power in organizations in America and around the world," says Alixandra Pollack, a vice president at Catalyst, a nonprofit group that promotes gender equality in the workplace. "Diversity can't only be the responsibility of women and minorities."

Some efforts are underway to vary the corporate landscape. Earlier this year, for example, Chevron Corp. pledged $5 million to expand Catalyst's Men Advocating Real Change (MARC) program. MARC helps men to understand the challenges women face in the workplace and to modify their behaviors to create more-equitable environments. Program participants spend a day and a half in facilitated conversations, speaking honestly about their experiences in the corporate world.

Men who have participated in the program say it opened their eyes to the issues women face and helped them recognize how they may have unintentionally blocked the career paths of women and minorities. Several said the program alerted them to an unconscious bias toward hiring people whose backgrounds and experiences mirror their own. In response, they've taken actions such as revising job descriptions to attract more diverse applicants, creating more-flexible schedules and bringing more women into their inner circles.

"What resonated with me is that I'm a leader of a large organization, and, if I don't speak up and make changes, no one will," says Kevin Lucke, who manages roughly 1,000 employees as vice president of supply chain for lubricants at Chevron.

‘There’s never been a worse time to be a man. They perceive that their power and authority is being threatened.’

Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic

Coming Up Short

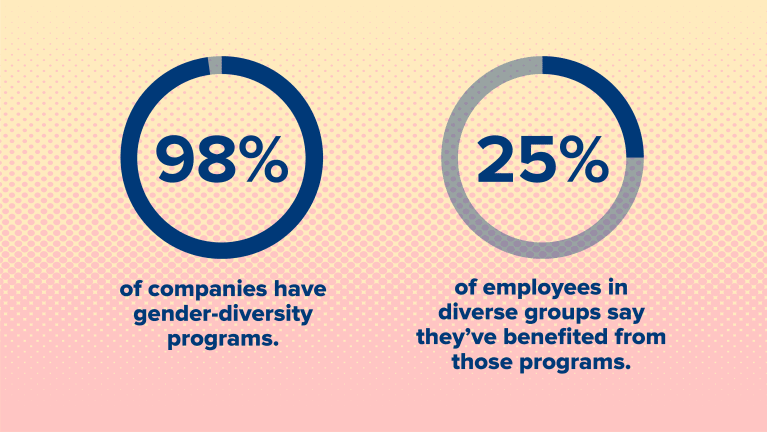

Most gender-diversity policies don't work, however, according to a study by Boston Consulting Group (BCG). It found that 98 percent of companies have such policies but only a quarter of the employees that they're designed to help say the policies are beneficial.

These are expensive failures: Companies spend more than $1 billion a year on inclusion and diversity, including by providing training programs, fighting lawsuits and paying settlements, estimates Matt Krentz, BCG's global leader for diversity, inclusion and leadership.

"It isn't enough just to have an inclusion program or sexual-harassment training," he says. "What we haven't seen, though are starting to see, is leadership making [gender diversity] a front-line priority."

Krentz says companies must give employees the appropriate training to broaden workplace diversity. Those charged with hiring, managing and promoting people must learn how to supervise inclusive teams, spot unconscious bias and open their minds to different perspectives.

Those who benefit from the status quo don't have much incentive to change it, and transforming a culture isn't easy under the best of circumstances, says Chamorro-Premuzic, who is also chief talent scientist at ManpowerGroup and a professor of business psychology at University College London and Columbia University.

After examining about 1,000 studies on gender, personality and leadership, as well as his own research, Chamorro-Premuzic concluded that too often companies choose managers for their confidence and charisma—traits typically more associated with men—than for their competence. He adds that clinical narcissism is almost 40 percent higher in men than in women, and those with that condition are more prone to bullying and harassment.

‘It isn’t enough just to have an inclusion program or sexual-harassment training. What we haven’t seen, though are starting to see, is leadership making [gender diversity] a front-line priority.'

Matt Krentz

In today's rapidly changing corporate climate, firms need leaders who can think critically and who are intelligent, curious and empathetic—in other words, people with high emotional intelligence, or EQ—and these attributes are more typically found in women. Chamorro-Premuzic writes that "positive leadership styles are associated with high-EQ leaders and most female leaders, while negative leadership styles are associated with low-EQ leaders and most male leaders."

He adds that an emphasis on emotional intelligence wouldn't benefit just women but also would boost men with those traits. The challenge is that for companies to recognize that their systems for hiring and promoting are far from ideal, they would have to concede that they're not the meritocracies they believe themselves to be.

"It's very hard for organizations to acknowledge, let alone admit, that many people who emerge as leaders—or at least a large portion of the leaders—are not effective or don't have what it takes to be effective," he says. "You're not as democratic as you think. You're not as objective as you think. You're not as unbiased."

The 2018 Corporate Pipeline

Diversity Equals Dollars

Broadening leadership composition could bring companies significant profits. For example, the plurality of managers are white men, according to the study by McKinsey and LeanIn.Org. Poor management is one of the most common reasons people leave their jobs, and the cost of replacement is often one-third of an employee's salary or more.

Meanwhile, both gender and ethnic diversity correlate with higher profitability and value creation, according to McKinsey. The firm found that companies in the top quartile for gender diversity on executive teams were 21 percent more likely to outperform on profitability.

"The business case for hiring diversity is there, but it doesn't appear to be changing hearts and minds," says Marianne Cooper, Ph.D., a sociologist at the VMware Women's Leadership Innovation Lab at Stanford University and an author of the Women in the Workplace reports. "That's troubling. What will lead companies to do the right thing?"

Lawsuits and bad publicity have sometimes sparked organizations to embrace change. Allegations of sexual harassment against top brass at Uber, CBS and NBC forced those companies to promise investigations into the charges and overhaul policies designed to prevent such behavior. However, Cooper notes, it's difficult for outsiders to know if anything substantial is going on beyond the public pledges.

Liz Marsh, director of strategic initiatives and chief of staff to Berkeley's chief information officer, won't discuss specifics of Kaskiris' case. She acknowledges, however, that Kaskiris' public pronouncements pushed the department to act.

"There became a sense of 'What the hell is going on here?' " Marsh says.

The initial staff survey found that 85 percent of those working in Berkeley's IT department were at least somewhat satisfied with their jobs. However, a large amount of the workforce perceived the environment to be negative, unfair and not inclusive. Many respondents stated, for example, that they have witnessed or experienced unfair treatment, bullying or harassment. Men and whites were more satisfied with the environment than women and people of color.

"We hadn't been putting energy into making sure that managers knew how to manage," says Marsh, adding that there wasn't enough money for training due to university budget cuts.

That has been changing. The department held a series of talks to instruct employees on what to do if they witness harassment or bullying. Management holds quarterly meetings with staff to discuss whatever is on employees' minds. Beyond that, managers simply walk around more often, to be attuned to what's going on within the ranks.

"It feels better," Marsh says.

Hope for the Future

There are diversity drivers beyond public scandal. Chevron has been recognized for years by various organizations for promoting inclusion. The energy company adopted Catalyst's MARC program in 2016 and adapted the policies to suit its needs. Chevron's program extends beyond a day and a half meeting to having groups meet regularly throughout the year. There are also single-gender groups that are melded to form coed units for discussion.

Chevron's Lucke says the program taught him that he had an unconscious bias toward hiring people like him: men with similar work experience. After realizing that, Lucke started to rewrite job descriptions to focus less on specific types of experience and more on leadership skills. He said that broadened the candidate pool.

Lucke oversees 16 plants, and for the first time two are led by women. There are about a half-dozen female plant supervisors, and three women are on his leadership team of seven—up from one.

- Implement a zero-tolerance policy stipulating that any kind of discrimination or harassment will lead to an employee’s dismissal.

- Use automated resume-screening tools to reduce bias.

- Require that a diverse group of individuals is considered for each open position and that those making hiring decisions also represent different genders, ethnic groups, ages, sexual orientations and religions.

- Make creating diverse teams a factor in determining managers’ raises, promotions and bonuses.

- Track the company’s progress in creating a diverse workplace. Examine whether strategies used in departments that have succeeded in building an inclusive team can be incorporated into other units.

Lucke adds that he often discusses the program with his direct reports and incorporates elements into his management meetings. Two of his direct reports have chosen to participate in the voluntary program.

"Chevron is a very process-oriented organization," he says. "But we have the power to change the processes."

Avi Kahn, president and chief executive officer of Hilti North America, says he became committed to diversity after volunteering to attend a MARC seminar. The leader of the division for the Liechtenstein-based provider of tools and construction services recalls being shocked when every woman in the group said she had been harassed at work. He was so astonished that he called his wife to share the news and was surprised again when he learned that she'd had similar experiences.

"Maybe I'm just naïve, but I couldn't believe it," Kahn says. "Women are just so resilient. What women face is not so clear to men."

Kahn has since become one of the more than 60 Catalyst CEO Champions for Change who have pledged to promote more female leadership in their organizations. His executive team of 11 now includes two women. Additionally, seven of the company's 25 division managers are women, up from three.

Kahn says the seminars caused him to alter how he views awarding promotions. "In general, men get promoted based on future promise. Women get promoted on what they delivered," he says. "Until you understand that, you may overlook women."

Theresa Agovino is the workplace editor for SHRM.

Explore Further