How to Bridge the Language Gap

Facing worker shortages, HR leaders are helping workers learn English, creating a new pipeline for middle-skill workers.

Introduction

Xochitl Chavez, 27, didn’t speak any English when she moved from Mexico with her two children in 2000 to join her husband in the U.S. Still, she was able to find a job at a McDonald’s in Georgia, and she spent the next eight years getting by on the few words she could pick up each day.

That changed when her manager recommended her for the McDonald’s “English Under the Arches” program, which helps employees improve their language skills so they can take on greater responsibilities.

The classes were convenient, with online sessions as well as face-to-face lessons. Not only were they free, but Chavez was paid for her time spent learning. Over the next 18 months, her English improved—and so did her work prospects.

Chavez was promoted from crew member to shift manager and then assistant manager.

Now she’s the store manager at a McDonald’s in Dalton, Ga., where she encourages her crew of mostly Spanish-speakers to take the classes and build a better future.

“You can do it,” she tells them. “You make more money, and you make your dream.” She knows firsthand: “It’s hard when you go someplace and you don’t know what to say.”

“You can do it,” she tells them. “You make more money, and you make your dream.” She knows firsthand: “It’s hard when you go someplace and you don’t know what to say.”

With worker shortages across many U.S. industries—and expected to only get worse—more leaders are looking to develop the talent they have. As Baby Boomers retire, there simply haven’t been enough young people born in the U.S. to replace them.

That’s why individuals from other countries will play a primary role in the growth of the workforce, according to a 2017 Pew Research Center report. Without new immigrants, the total U.S. working-age population would drop by almost 8 million, or more than 4 percent, by 2035, from 173.2 million in 2015, Pew researchers project.

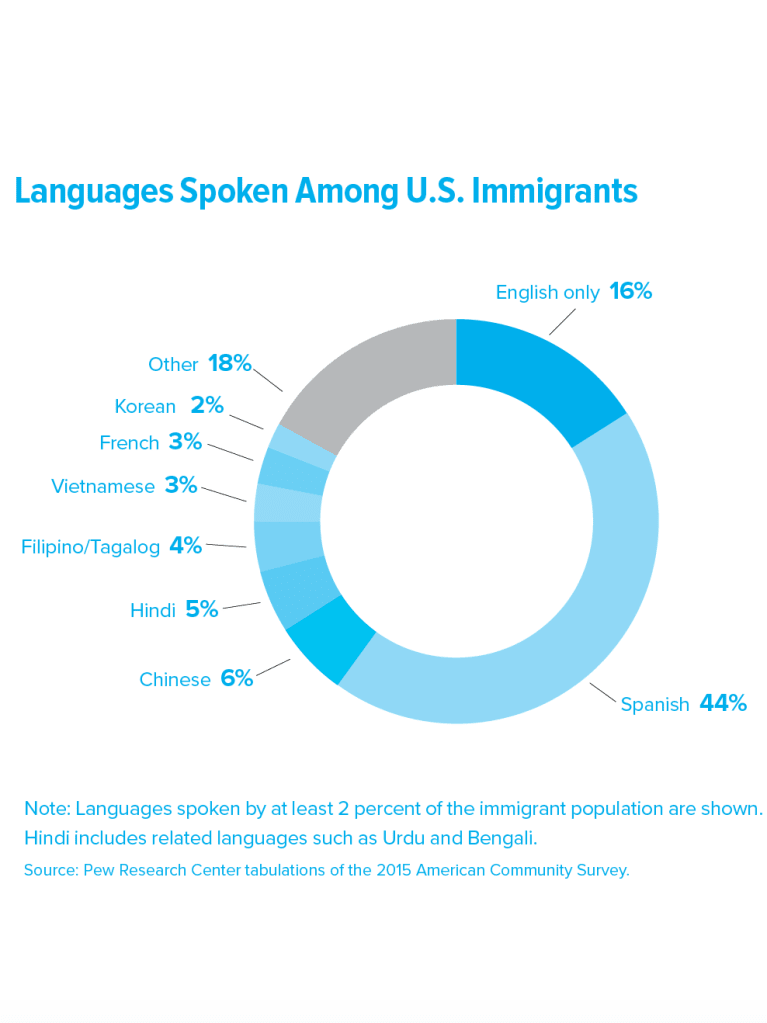

Despite the ongoing debate over U.S. immigration policies, the U.S. population is already incredibly diverse. More than 40 million people living here were born elsewhere. About half of all immigrants ages 5 and older have limited English proficiency, according to the Pew report.

Untapped Potential

McDonald’s tested its English classes in a series of pilots in 2007 and launched them nationally in 2015 as part of its “Archways to Opportunity” program, which includes other educational assistance. In total, about 6,100 workers have completed the classes at more than 40 sites nationwide.

While offering language instruction serves a critical business need to prepare workers for customer-facing roles, “we also see a great impact on people’s personal lives and their ability to speak the language,” says Lisa Schumacher, director of education strategies at McDonald’s Corp., headquartered in Oak Brook, Ill., just west of Chicago. “Helping them get to a place where they can more comfortably speak English is important to us.”

McDonald’s contracts with local community colleges to offer courses, which use a curriculum that has been tailored to crew members’ needs. Employees with limited English skills are enrolled in conversation classes, “Shift Basics” or “Shift Conversations,” while those who are more fluent sign up for “Shift Writing.” Managers and management trainees can take a class to help them deliver performance evaluations in English. Courses range from eight to 22 weeks and are voluntary, as are all of the programs highlighted in this article.

Improved retention rates suggest that the program is working. In the high-turnover fast-food industry, 88 percent of participants are still working at McDonald’s one year after completing classes, and 75 percent remain with the company after two or three years.

“The fact that they are paid for their time in the class I think is critical to our success,” Schumacher says.

Balancing in-person learning with virtual lessons is also key, she says. When participants take a class alongside people they know and trust, it “takes away a level of fear and anxiety about going into a new environment and learning something they may not feel comfortable learning,” Schumacher says.

At graduation ceremonies, she has watched the adult students hugging and thanking their instructors. “I think the relationships they create with their fellow students and their instructor are critical,” she says.

Although online modules may be easier to implement, Schumacher doesn’t think they’re a good idea for entry-level workers.

“Learning another language is hard. There aren’t necessarily any easy solutions,” she says.

To determine what works best for your company, you must first understand the challenges your employees face. When setting up an in-person class, for example, don’t expect employees who rely on public transportation to travel an hour to get there.

Celebrate Learning

Contextualized English instruction has also proved helpful in the retail industry, where an estimated 1.5 million employees have limited English proficiency.

After 16 weeks in a pilot program funded by the Walmart Foundation, 37 percent of the total 1,000 participating employees were promoted at Kroger in Houston, Publix in Miami and Whole Foods in New York. And 82 percent held the same position for five years before their promotion, says Jennie Murray, director of integration programs at the National Immigration Forum, a nonprofit immigrant advocacy group based in Washington, D.C.

“That’s a really good indicator that this is a pipeline for internal promotions and middle-skill jobs that employers are not currently tapping into,” Murray says.

The participants’ managers, who were surveyed before and after the classes, reported an 87 percent improvement in customer service and an 89 percent rise in store productivity. The forum partnered with Miami Dade College and the Community College Consortium for Immigrant Education on the initiative, “Skills and Opportunity for the New American Workforce.”

The employees weren’t paid for their instruction time, but classes were scheduled just before or after employees’ work shifts in various locations.

The employer’s level of involvement appeared to be a more significant factor in the employees’ success than whether the classes were held at the worksite, Murray says. When company leaders promote the English classes internally, welcome students at the start and celebrate their achievement with them at the end, it can make a world of difference, she says.

A digital literacy component was added to help workers master their store’s technology, and a mobile app supplemented their language learning.

The pilot is part of the National Immigration Forum’s larger “New American Workforce” initiative, which offers English and citizenship classes and legal services to those working at 300 participating organizations in eight cities.

To build on that success, more than 20 corporations, led by Walmart and Chobani, are preparing to roll out later this year the Corporate Roundtable for the New American Workforce to sponsor research and develop best practices for integrating immigrants into the workforce.

“They’re coming together for a long-term effort, but it’s time-sensitive because we’re in worker shortages that were implicated 10 to 20 years back,” Murray says.

Find the Right Partners

Sometimes good ideas are born out of necessity. Two years ago, Yohanys Castro was the HR director at a Los Angeles area hotel that was being upgraded to become a Hyatt Regency with Forbes four-star status. She knew she would have to lay off workers if she couldn’t help them improve their poor customer service skills, which were linked to their limited English comprehension. Some housekeepers would avoid guests because they feared they wouldn’t understand a request.

“They would put their head down and pretend to be busy when a guest walked by. That’s not what we wanted,” she says. “We wanted people, even with their limits, who would interact.”

She empathized because she grew up watching the struggles of her own parents, who were Cuban immigrants. As a child, she translated for them.

“I was their liaison between their world and the world we live in today,” she recalls. “As I became older, it was sad to see my parents as vulnerable people and not as my heroes, my protectors.”

Castro sought help from the Los Angeles Workforce Development Board, which provided a $100,000 grant to the Los Angeles Hospitality Training Academy, a nonprofit arm of the Unite Here Local 11 labor union, to provide onsite English classes and other needed training for hotel staff.

After just two weeks of instruction, Castro noticed a big difference in the housekeepers.

“They would see me in the hallway and would use what they were learning to talk to me,” she says. “They would sit in their lunch hour and practice for the next class.”

She understands the immigrants’ struggle, how hard they work, leaving little time for themselves. The classes were “one way we could take care of them for taking care of us. It was just a dream I had that became a reality,” says Castro, who now is vice president of HR for Hilton Los Angeles/Universal City. She is planning to offer English classes there as well.

“The biggest reward you’re going to receive in your career is to give the gift of education to your employees,” she says.

Climbing the LadderWhen Mario Bandera interviewed at a Los Angeles-area hotel five years ago, the 25-year-old Cuban native had been in the U.S. only a few months. He spoke no English but desperately needed work. “If you give me the opportunity, I will take my job seriously,” he told the hiring manager in Spanish. “You will never have anything bad to say about me.” He got a job cleaning guest rooms. Two years later, he jumped at the chance to take onsite English classes to help housekeeping staff improve customer service as the hotel transitioned to become the Hyatt Regency Los Angeles International. “It was really, really amazing,” Bandera says. “I could study and work at the same time. For me, it was perfect. This was a good opportunity in my life.” In 2016, Bandera was promoted to housekeeping supervisor, and he has high ambitions for the future. “My goal is to be a manager or something bigger,” he says. |

Build Relationships

If English classes aren’t feasible, there are other ways you can help surmount the language barrier. For day-to-day communication, managers often rely on other employees to translate for those who speak little or no English. Or supervisors get by with hand gestures and Google translations. Some executives hire managers who are bilingual, while other companies provide foreign language training for their supervisors in locations where the majority of employees don’t speak English.

Several Phoenix-area employers pair new workers who speak limited English with a co-worker who can help orient them, says Niki Ramirez, SHRM-CP, founder of HRAnswers.org.

“Language is what connects us and makes us visible to one another. It produces a conduit to build relationships,” says Ramirez, who is fluent in English and Spanish.

“Whether finding a document in their native language or finding a bilingual co-worker to support them, it really goes a long way to creating a civil and humane workplace,” she says. It tells the workers, “Hey, I see you, and your contribution is important to us.”

Ramirez translates company handbooks into Spanish for clients and sees how appreciative employees are when they receive a document they can understand. Another easy way to build human connection: Let your employees choose the music in their breakroom so they don’t hear English-language tunes all the time.

International potlucks are popular at United Electric Controls, a manufacturing company in Watertown, Mass., where workers hail from 29 different countries, ranging from Venezuela to Vietnam, Somalia to Singapore, says Terri Pollman, the company’s HR director. Onsite English classes helped workers gain confidence to apply for apprenticeships, she says.

Can Employers Require Workers to Speak English?Steer clear of implementing English-only policies, which are permissible only in limited circumstances where there is a legitimate business need, such as for ensuring operational safety, says attorney Jaklyn Wrigley, an attorney with Fisher & Phillips LLP in Gulfport, Miss. For example, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission presumes such approaches violate Title VII’s prohibition against national origin discrimination, and many states, including California, have passed legislation barring English-only workplaces. In addition, a National Labor Relations Board judge recently found that the policies violate the National Labor Relations Act because they could restrict employees from discussing the terms and conditions of their employment. |

Translate Key Information

Sometimes a professional translator is needed, says Pablo Pineda, HR manager at a Smithfield Foods plant in San Jose, Calif., where about 80 percent of the 155 employees have limited English proficiency.

Pineda, who is bilingual, translates for the plant’s 102 Spanish-speaking workers, but he had to hire a professional to do the same for the 26 employees whose primary language is Vietnamese.

“She’s walking the floor, jumping on issues right away,” he says of the translator, who comes in a few times each week.

Schedules at the plant are posted in English, Spanish and Vietnamese, and workers also receive written translations for safety training, benefits information and handbook policies.

The federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) requires that employers provide safety training “in a language and vocabulary workers can understand.” The agency has free educational materials in multiple languages at www.osha.gov.

Safety training at Duncan Family Farms in Buckeye, Ariz., is offered in both English and Spanish through the company’s recently launched DFF University, says Tina Huff, vice president of HR. An online English learning program, Mango Languages, which has a mobile app, is also included in the company’s educational offerings. Those interested in learning Spanish can use it as well.

In addition, Huff recently implemented a new human capital management system that allows her to upload policies in Spanish as well as English.

When workers log on, they can read company policies, performance evaluations and other documents in the language of their choice. It was worth the investment, Huff says, given that about half of the 500 employees have limited English proficiency.

“We have a lot of employees who have been with us for many years,” she says. “We want our employees to be able to grow and develop as we’re introducing new technology.”

For more routine communications, here are a few simple strategies shared by those who work with employees with limited English skills:

Make eye contact. “Even when you are using a translator, pay attention to the person you are talking to, not the translator. You can tell a lot of things by facial expressions,” Pineda says.

Use nonverbal communication. Demonstrate what you want them to do, Ramirez says. Highlight the important parts of written materials.

Show respect. Speak slower, not louder. Avoid contractions, slang and idioms, Pineda says.

Be patient. Overcoming language barriers does take time and effort and maybe even additional dollars, Ramirez says.

But at the end of the day, you’ll have employees who are loyal, productive and happy, she says. “And they show that by getting their jobs done well.”

Dori Meinert is senior writer/editor of HR Magazine.

Photos courtesy of McDonald's and Bill D. Medrano.