What Will the Workplace Look Like in 2025?

The shift to remote work will be among the biggest business trends in the coming years, though it won't be the only lingering effect from the pandemic.

Before the pandemic, General Motors Co. was moving toward giving employees more flexible schedules. However, the coronavirus outbreak threw that effort into overdrive.

In November, the Detroit-based automaker announced it was hiring 3,000 technical employees, the majority of whom will work remotely. The company is offering more full-remote experiences than ever before. Leadership’s confidence to take such a bold step stems from the performance of the teams that are working remotely because of the COVID‑19 pandemic.

“Our workforce was able to meet the new challenges [while working from home] without missing a beat,” says Adam Yeloushan, GM’s human resources executive for global engineering. “We can [work remotely] well. We can do it effectively.”

‘The role of the office has changed. People aren’t going to go back to five days a week. Offices are going to be hubs of innovation and social interaction.’ - Bhushan Sethi

Working from home became a necessary stopgap measure to keep companies running amid the COVID‑19 crisis, but it has evolved into a new business paradigm. Many employees praise their newfound flexibility, while company leaders continue to manage their businesses effectively—and less expensively—even when employees aren’t in the office. Employers also welcome the broader pool of potential job candidates, since remote employees can live anywhere.

“The role of the office has changed,” says Bhushan Sethi, joint global leader, people and organization, at global consulting firm PwC. “People aren’t going to go back to five days a week. Offices are going to be hubs of innovation and social interaction.”

That shift will be among the biggest business trends in the coming years, though it won’t be the only lingering effect from the pandemic. The virus pushed companies to grapple with health and safety issues like they never had before. Not only have they reconfigured workplaces to prevent infection, they have also grappled with how to address the pandemic’s toll on employees’ physical and mental health. Those efforts will continue to better prepare companies for other emergencies.

The killings of George Floyd and others while in police custody and the ensuing protests is the other development from this year that will reverberate through the business community for the foreseeable future. Floyd’s death laid bare the overall inequities in the U.S. and prompted soul-searching in the business sector. Companies have promised to increase diversity within their ranks—especially among executives—and the fulfilling of those pledges is now expected to top corporate agendas.

While the combination of the pandemic and social unrest have led to major new trends, the upheaval has also pushed other long-standing issues, such as environmental concerns, worker activism and rapidly changing technology, to the forefront of C-suite executives’ minds.

These are six major trends that will ripple through companies until at least 2025:

1. More employees will work from home.

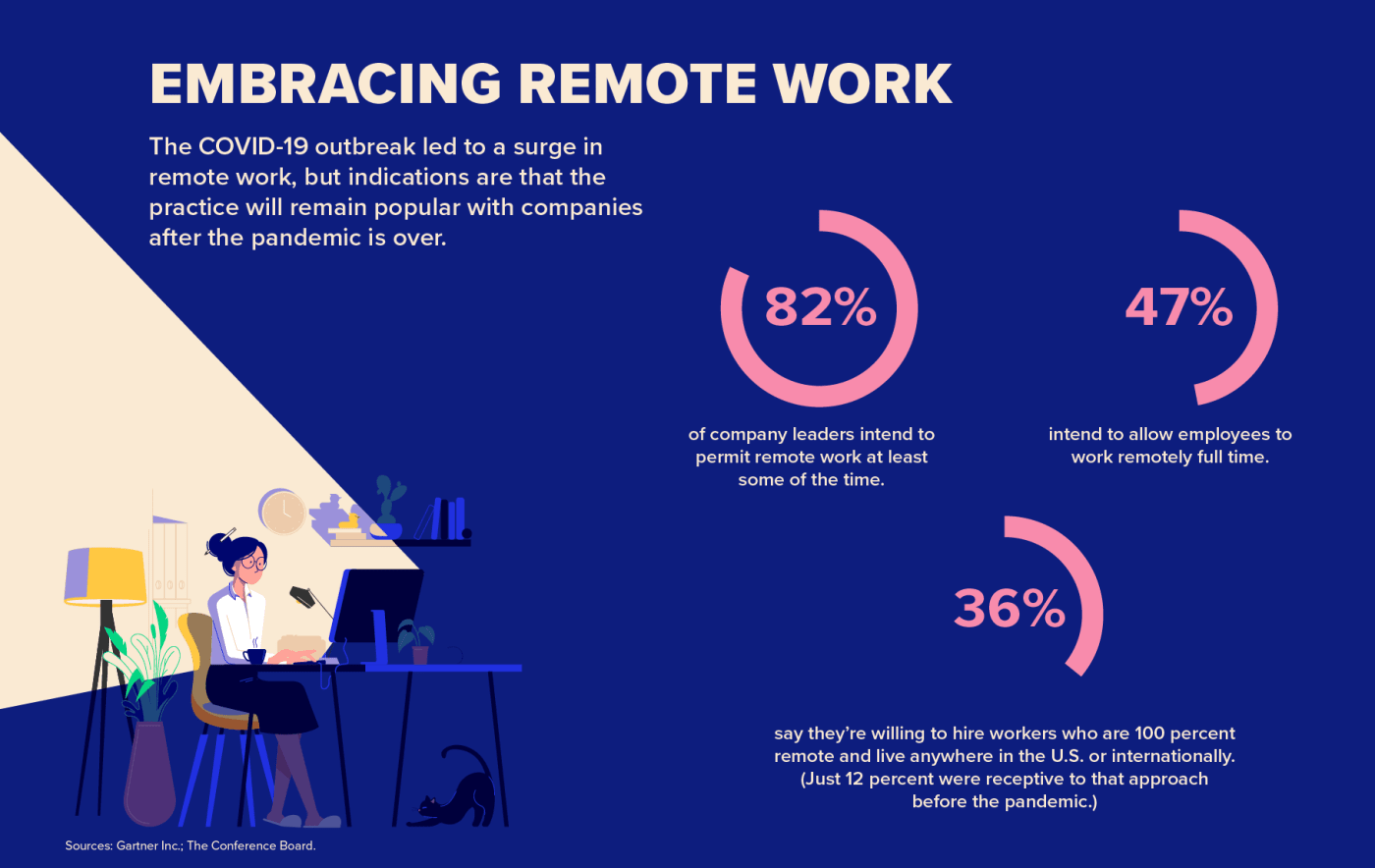

The world should start returning to “normal” in 2021 as the COVID‑19 vaccine is distributed. The new normal won’t include nearly as many office workers commuting daily to a company facility. A large majority—82 percent—of executives say they intend to let employees work remotely at least part of the time, according to a survey by Gartner Inc., a Stamford, Conn.-based research and advisory firm. Nearly half—47 percent—say they will allow employees to work remotely full time.

Meanwhile, 36 percent of companies say they’re willing to hire workers who are 100 percent remote and live anywhere in the U.S. or internationally. Just 12 percent were receptive to that idea before the pandemic, according to The Conference Board, a New York City-based research nonprofit.

Reconfiguring the office for this new scenario is an interesting dilemma for companies. Executives expect that individuals will want more personal space even with a COVID‑19 vaccine available, though businesses will likely reduce their real estate holdings if employees aren’t in the workplace full time. Seventy percent of companies expect to shrink their real estate footprint in the next two years, according to CoreNet Global, a nonprofit organization made up of corporate real estate executives.

Design experts predict that more companies will adopt what is known as “hoteling.” That means employees no longer have assigned seating but locate where there’s space available for the type of tasks they’re working on. Some areas will be earmarked for quiet work while others will be designated for group discussions, for example.

“The workspace needs to be more agile,” says Jamie Feuerborn, director of workplace strategy at New York City-based design firm Ted Moudis Associates. She adds that companies are looking at flexible furnishings, such as desks that can be easily moved and have adjustable privacy panels.

Remote working is not for every company, nor is it without risks. Some jobs require people to be onsite, and surveys have shown that some individuals have had trouble achieving work/life balance while working from home. There’s also a fear that corporate culture and innovation will suffer if co-workers aren’t in the same space.

Sixty-five percent of employers say it has been challenging to maintain morale, and more than one-third say they’re facing difficulties with company culture and worker productivity, according to a survey by the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM). Three years ago, IBM, a pioneer of remote work, called most of its off-campus workforce back to the office to improve innovation.

Now it seems that companies are more aware of the pitfalls of a remote workforce and seek to approach remote work with an intention that was lacking in the rushed response to the pandemic. Over the summer, Facebook advertised for a director of remote work, whose responsibilities would include developing strategies and tools to keep the business running no matter where employees are located, and coaching managers on how to adjust to the new remote-work structure. Facebook co-founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg said 50 percent of the company could be working from home within the next five to 10 years.

GM’s Yeloushan says the company can adjust to any issues or problems. “All because we’re doing some things today doesn’t mean we’ll be doing the same tomorrow.”

2. Companies will invest heavily in health, hygiene and safety.

COVID-19 turned a spotlight on worker health and safety in all industries—not just those known for being dangerous—as even people who sat at computers all day landed in intensive care units after contracting the coronavirus. Employees who have returned to their workplaces wear masks, sanitize surfaces and social distance, and some even submit to temperature checks. Those measures are likely to transform into workplace testing protocols, state-of-the-art ventilation systems, and high-tech detection and disinfectant tools.

“We’re assured of having another [pandemic],” says Cristina Banks, director of the Interdisciplinary Center for Healthy Workplaces at the University of California Berkeley School of Public Health. “Our mobility around the world is at the peak, and there’s no stopping the spread. We need to plan for that.”

The planning is already happening. A vast majority of business executives—83 percent—say they expect to hire more people for health and safety roles within the next two years, according to a report by consulting firm McKinsey & Co. It’s the sector that’s predicted to have the most hiring.

‘We’re assured of having another [pandemic]. Our mobility around the world is at the peak, and there’s no stopping the spread. We need to plan for that.’

Cristina Banks

Concerns extend beyond employees’ physical health. The pandemic, the recession and social unrest have caused increased anxiety, depression and stress in the general population. Employers had been increasing their mental health benefits before the COVID‑19 outbreak and are now stepping up even more. Nearly three-quarters (72 percent) of companies plan on improving their mental health offerings next year, according to a survey by PwC.

Many companies have heavily promoted their employee assistance programs, increased the number of paid sessions with mental health counselors for employees while waiving or lowering co-payments, and added more digital tools to help people calm and focus themselves. Some organizations are training managers to spot signs of distress.

“We know that having a strong mental health strategy will be a critical priority,” says Abinue Fortingo, a health management director at Willis Towers Watson. He says employers are combing through claims data to understand how to put together the best plan design.

3. Companies will continue striving to increase diversity, equity and inclusion.

The $8 billion that McKinsey & Co. says companies spend annually on diversity, equity and inclusion programs is not money well spent. White men still occupy 66 percent of C-suite positions and 59 percent of senior vice president posts, according to a study by McKinsey and LeanIn.Org. White women hold the second largest share of such positions, though they lag significantly behind their male counterparts, filling only 19 percent of C-suite jobs and 23 percent of senior vice president spots. Men of color account for 12 percent and 13 percent of such roles, respectively, while women of color hold only 3 percent and 5 percent, respectively.

Such statistics entered the public consciousness in the aftermath of George Floyd’s death, putting more pressure than ever on companies to diversify their ranks.

Some companies are opting to initiate conversations that encourage their employees to talk openly about issues such as racism, sexism, bias and prejudice. Yeloushan says hiring more remote workers will allow GM to tap into a much wider talent pool that will help diversity the workforce.

Meanwhile, in October, Seattle-based coffee company Starbucks said part of its executives’ pay would be based on their ability to build inclusive and diverse teams.

It’s too soon to say if such efforts will spark real change, though there are some positive signs. Eric Ellis, president and chief executive officer of Integrity Development Corp., a West Chester, Ohio-based consulting firm, says the strategy sessions he holds about improving diversity, equity and inclusion now include more CEOs and not just human resource executives. “CEOs are more interested now and putting more pressure on their organizations to change,” he says.

4. Workers will demand better treatment for themselves and their communities from their employers.

Thousands of workers at companies such as McDonald’s, Target and Amazon, as well as at numerous hospitals, staged strikes this year to protest unsafe working conditions amid the pandemic.

Such actions followed two years of employee demonstrations over various issues—though not pay—signaling that employees were expecting more from their employers. Last year, for example, Amazon employees walked out over the company’s climate policies, while Wayfair workers left company facilities over sales of furniture to immigrant detention centers in the U.S.

Overall, work stoppages numbered 25 last year, more than triple the amount in 2017, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

‘People are looking for alternate ways to communicate, and virtual reality is a good fit. It allows a level of interaction that goes beyond voice and video. It’s much more personal.’

T.J. Vitolo

The activity hasn’t reversed the years-long decline in union membership, although that could change. President-elect Biden ran on a pro-labor platform that could translate into the removal of some obstacles to unionization implemented by the Trump administration. Even without more unions, workers—especially younger ones—increasingly expect their employers to take an active role in addressing society’s problems.

“We’re seeing companies have more of a social conscience,” Ellis says. “I think that’s part of the value system of the up-and-coming generation.”

The idea is taking hold. In 2019, the Business Roundtable released a new definition of a corporation and outlined a company’s purpose as extending beyond making profits to considering how its actions affect all stakeholders, including employees, customers and suppliers.

5. Organizations will re-examine how they impact the environment.

The COVID-19 pandemic is a brutal reminder of the ravages of climate change.

The novel coronavirus evolved from a virus common in bats, though it’s unclear how it passed to humans. Experts say deforestation, which pushes animals farther out of their natural habitats, could have been a factor, as it puts animals closer to people. What is known is that climate change is making the death toll worse. A Harvard University study found that a small increase in exposure to air pollution leads to a large increase in COVID‑19-related death rates.

“Businesses found themselves unprepared for COVID,” says Rachel Hodgdon, president of the New York City-based International WELL Building Institute, which has programs to create buildings, interiors and communities that promote health and wellness. The institute recently started a COVID‑19 certification program to help all types of facilities protect against the disease.

To make matters worse, businesses are being buffeted simultaneously by disasters caused by climate change. This year, fires raged on the U.S. West Coast, and hurricanes hit many states, all while the country was fighting the virus.

Having more employees work from home will help the environment as fewer people commute and office buildings use less energy. More action is required, however, and experts expect more companies to hire chief sustainability officers.

Many companies already have such roles, though some practitioners only ensure that their organizations meet basic laws and standards. That won’t cut it anymore, thanks to the greater emphasis on health and the environment. Going forward, chief sustainability officers will be expected to look at their company’s environmental impact on workers, suppliers, customers and communities. “That will all be tied back to the business strategy,” says Anthony Abbatiello, global head of leadership and succession consulting at Russell Reynolds, a New York City-based executive search and consulting firm.

6. Technology’s rapid transformation will continue, forcing companies to rethink how to integrate people with machines.

The pandemic forced employers to adopt more digital and automated solutions practically overnight, as organizations sought to severely limit—or end—human interaction to stop the spread of the coronavirus.

The McKinsey study found that 85 percent of companies accelerated the digitization of their businesses, while 67 percent sped up their use of automation and artificial intelligence. Nearly 70 percent of executives say they plan to hire more people for automation roles, while 45 percent expect to increase hiring for positions involving digital learning and agile working.

One area that’s expected to grow enormously is companies’ use of virtual and augmented reality, as fewer employees work at the same location. Companies are already using these technologies for training, telemedicine and team-building events.

“People are looking for alternate ways to communicate, and virtual reality is a good fit,” says T.J. Vitolo, director and head of XR Labs, a division of New York City-based Verizon Communications Inc. “It allows a level of interaction that goes beyond voice and video. It’s much more personal.”

Robot use boomed during the pandemic, as companies sought to reduce workers’ exposure to the coronavirus. For example, San Diego-based Brain Corp. said use of its robots by U.S. retailers surged 24 percent in the second quarter of 2020 compared to the year before, as companies used the machines for tasks such as cleaning stores.

The increased use of technology will eliminate jobs. That means companies will need to reskill employees to prepare them for new tasks and responsibilities.

“I think reskilling will be the foundation of the new economy,” says Ravin Jesuthasan, a managing director at Willis Towers Watson. “What it’s going to require is a clear understanding of how to get the optimal combination of people and machines.”