Hiring Challenges Confront Public-Sector Employers

Federal, state and local agencies are looking for the next generation of civil servants.

Only a few years ago, applying for a job with the Pennsylvania state government could be a daunting process. Posted jobs had vague, bureaucratic titles like "Administrative Officer 1." Applicants had to take written exams at a testing center. Some waited months for a civil service commission to respond by mail before they could interview. Many had moved on by then.

"It was really just a very slow and painful way of hiring and wouldn't necessarily get the person with the right skills in the door," says Reid Walsh, deputy secretary for human resources and management for the commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

Things changed in early 2019, after state lawmakers agreed to streamline the 1940s-era system. Now, Walsh's agency oversees a centralized website, where job seekers apply for positions that are more clearly defined. Testing and scoring is folded into the online application process, which administrators track closely.

For corrections officer positions, which required candidates to take written examinations until recently, the change had an immediate impact.

"We saw probably triple the number of applicants within the first week of removing that from a test center environment to applying online for the job," Walsh says.

There are good reasons why government employers carefully screen applicants, but removing some obstacles within the process is one of several strategies the public sector can use to do a better job of recruiting talent, analysts say.

Rolling out the welcome mat is of paramount importance in the coming decade, as federal, state and local officials compete with the private sector for young workers who will replace retiring Baby Boomers.

The Next Generation

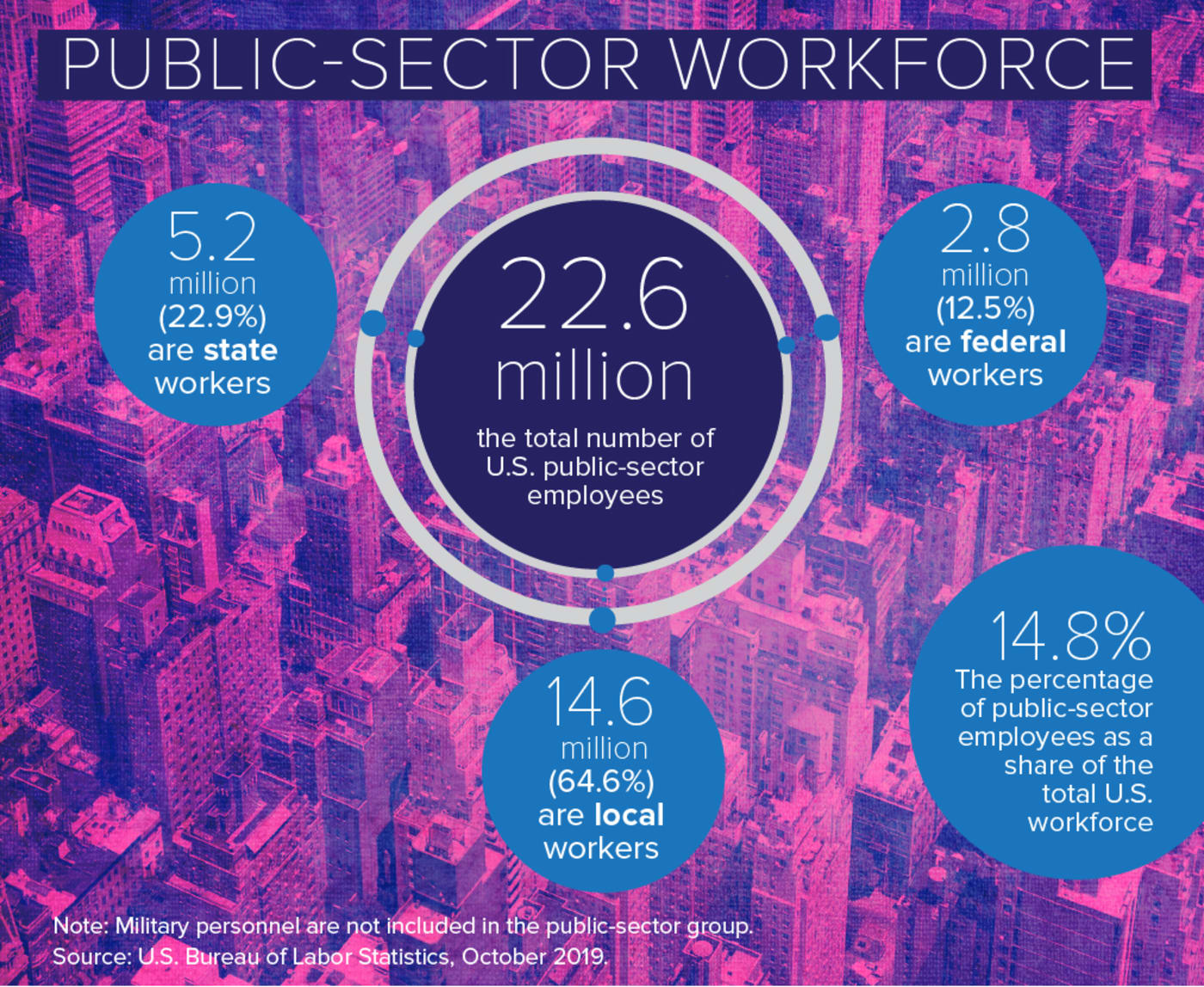

Millennials, the generation born between 1981 and the early 1990s, are projected to make up 75 percent of the global workforce by 2025, according to Forbes. Nationally, employees who are under 35 make up only about 27 percent of the public workforce, according to the most recent data provided by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The primary reason for the disparity? Younger applicants won't wait.

"It can take six months to even get back to someone about a position," says Rivka Liss-Levinson, director of research with the Center for State and Local Government Excellence in Washington, D.C. "In today's world, people don't have that kind of time to wait. [So] the best talent is going to the private sector, where they can more quickly recruit you and offer you a job."

Additional negatives typically weigh against government employers. They generally offer lower pay than the private sector, they can be inflexible about work schedules and telecommuting, and they're often considered culturally and technologically obsolete.

Consider, too, that government employees, from front-line workers to high-ranking administrators, can bear the brunt of public disrespect and political brinksmanship. Nearly 400,000 federal employees were furloughed in late 2018 and early 2019 as President Donald Trump and the Democratic-controlled House fought over budget priorities. The partial government shutdown lasted 35 days, the longest in U.S. history.

Engagement Challenges

A 2019 survey of federal employees conducted by the U.S. Office of Personnel Management (OPM) found that morale declined from the previous year. The overall employee engagement score of 61.7 out of 100 represented a 0.5-point drop, although the metric varied across different agencies, according to the Partnership for Public Service and Boston Consulting Group, which analyzed the data. By comparison, the analysis found that the private sector's 2019 employee engagement score was a more robust 77.

Jeff Pon, SHRM-SCP, who served as OPM director for eight months in 2018, acknowledges that political turmoil has sullied the image of public employment and may discourage people from wanting to work for the U.S. government. This is unfortunate, he says, given that the institution has "some of the finest people in America" doing truly innovative things.

Aspects of the federal government are indeed monolithic, says Pon, who was chief human capital officer for the U.S. Department of Energy from 2006 to 2008 before serving five years as chief human resources and strategy officer for the Society for Human Resource Management. Some departments are still dependent on the early computer program COBOL, and Pon's own former agency continues to store mounds of employee retirement documents within a former mine in Pennsylvania.

"One thing I tried to do on my watch is to have all new retirees, applicant retirees, be digital," Pon says. "They're getting rid of the paper, but still every other week there's a semi-truck full of paper going to the caves."

More recently, the federal government may have become a bit more attractive as an employer. Late in 2019, Democratic congressional leaders announced a spending agreement with the Trump administration that will result in paid parental leave for 2.1 million civilian workers. New moms and dads in the federal workforce will be able to take up to 12 weeks off with pay—a perk that's valued in any U.S. workplace.

"This is an important step in terms of enabling a federal job to be a good job, and then there's probably a chance for the federal government to be an influencer," says Dan Vogel, North American director for the Centre for Public Impact in Arlington, Va.

Keeping Up with the Times

Government officials know they lag behind the private sector in many respects. In a 2019 Deloitte survey of hundreds of public-sector employers across the globe, HR officials said their organizations are falling short in adopting modernization techniques.

For example, 56 percent of respondents said it's important for government organizations to knock down silos and take more of a "team" or "cluster" approach, but only 3 percent indicated their organizations are ready to move in that direction.

Seventy-one percent of respondents said converting paper records into cloud-based digital information is important. Only 33 percent said they were ready to implement the change.

"All of our 'paperwork' is [actual] paperwork," says Kim Ferullo, SHRM-SCP, director of human resources for Talbot County, Md., when asked about digital conversion.

Her office oversees a full-time workforce of 250 that skews older. Luring new employees can be challenging because at least one neighboring county government pays better wages, she says. Publicly backed pensions remain an attractive perk for government units like hers, Ferullo says, but young people might not consider rural Maryland as exciting as one of the major metro areas in the Northeast.

"That's something that is a challenge for us, and I'm still trying to get my arms around it," she says. "I just picked up and moved my family here three months ago, so I find it interesting and exciting. But for a young, single Millennial, if you weren't born and raised here, you might not pick it as your target area."

Denver has a good problem. It's adding 1,000 new residents per month in the metro area, officials say.

But with such rapid growth comes greater demand for services provided by the city-county government, which must hire more municipal employees to keep up.

"We're really challenged because we're up against every employer in the market looking for the top workers," says Diane Vertovec, Denver's director of marketing and communications.

In 2016, her department oversaw creation of a branding campaign to encourage the area's multigenerational workforce to apply for positions in the municipal government. Stakeholders who helped steer the initiative were enthused about the potential excitement that could be associated with working for the Mile High City.

The slogan "Be a part of the city that you love" became the linchpin for a marketing blitz that included billboards, social media ads and signage wrapped around public transit vehicles. A number of city-county employees served as "brand champions" for some of the messaging.

Between 2018 and 2019, Denver saw a 19 percent increase in the number of applications it received, to 160,000 from 135,000, according to figures provided by Vertovec. The number of first-time applicants rose 20 percent, to 5,514 from 4,605. Traffic at Denver's jobs website jumped 217 percent during the period.

The successful effort would be for naught, Vertovec notes, if new employees didn't like the jobs and work environment they encountered upon being hired.

"It's not getting them; it's keeping them," she says. "It's not just engagement; it's employee satisfaction." —M.R.

New Approaches

Ferullo plans to examine pay levels in 2020 and begin implementing "stay interviews"—the opposite of exit interviews—as a way to find out which parts of the county's work culture resonate with employees.

She wants to find out: "Is there something in their job that they find interesting and appealing? Is there something they would like to add to their skill set?"

She wants to make sure they're happy and want to stay.

There's good news about Millennials where the public sector is concerned. Although members of this cohort carry a disproportionate share of college-loan debt, they're not obsessed with wealth, observers say. They also are not necessarily interested in holding down the same job for 40 years just because it provides a steady paycheck. They prefer interesting experiences and mission-driven work that can make a difference in peoples' lives—in short, the very qualities that many government jobs can provide.

"You've got a generation of young people who are probably more purpose-motivated than any before," says Vogel, whose Centre for Public Impact advises city governments. "There's something missing in how we're communicating what it means to be a public servant and the opportunities to do impactful work."

Where government may fall short is in identifying career paths for prospective employees and new hires, says Liss-Levinson of the Center for State and Local Government Excellence. "That makes a big difference in terms of people wanting to stay—a feeling that there's this progression and this trajectory they have to this career."

Observers say employees who work for state and local governments may find more satisfaction in their jobs because the tangible results of their efforts are more apparent. Federal government work, by contrast, can be seen as nebulous.

Pennsylvania state employee Su Ann Shupp, 34, says she feels like she's helping to move the needle in protecting the environment as a land conservation coordinator for the Department of Conservation and Natural Resources.

"I couldn't imagine working anywhere else," she says.

It almost didn't happen. Shupp was hired nearly five years ago under Pennsylvania's previous system, the one that included a written test and months of waiting. What was particularly frustrating, she says, was that she'd already had a tryout of sorts as a contractor for the state. She offered testimony to lawmakers about the antiquated system.

"If I did not have a family member who had previously been working for the state of Pennsylvania and I did not know about the gold at the end of the rainbow, I probably would not have been such an obstinate person," Shupp says.

Both the public and private sectors are under increased pressure to embrace technology and automation, but that doesn't mean they'll be hiring fewer people in coming years.

Jobs will be redesigned, experts say, as software and machines take over rote functions, thus freeing up humans for more significant tasks.

"When people heard about the ATM, they believed it would be the end of the bank teller. It's been quite the opposite," says Sean Morris, Deloitte's government and public services human capital leader. "What we've seen is a significant increase in the number of individuals in the financial services industry and, most importantly, the number of services that are offered to you and I on a daily basis."

Deloitte uses the term "superjobs" to describe this melding of technology and human talent. Government is considered behind the curve. In a survey the consultancy published in 2019, most public-sector employers agreed that the superjobs trend is important, yet only about half of these respondents said their organizations are prepared for it

That's unfortunate, futurists say. According to Morris, everyone stands to benefit when, for example, public health guardians use analytic software to help predict dangers to citizens.

"A more common example would be a social worker going into a home and having the technology that is able to interpret the conversation," he says. "They're not writing. They're looking at the facial expressions of the family. Those technologies are out there, and they're elevating those human skills because they've got automation at hand." —M.R.

Mike Ramsey is a Chicago-based freelance writer.

Illustration by Roy Scott.