Youth Apprenticeships: A Solution to the Labor Shortage?

U.S. employers across the country are adopting a long-used European model to close the skills gap.

Credit: CareerWise Colorado

Forget politics.

The lowest unemployment rate in 50 years makes for strange bedfellows. Consider New York City, the culture, finance and typically liberal hub that's home to 8.4 million people, and Elkhart County, Ind., the U.S. epicenter of recreational vehicle manufacturing with a population of 206,000, most of whom vote Republican. Both launched a youth apprenticeship program this fall to tackle the acute labor shortage.

Each program is based on a 3-year-old effort started by Denver-based nonprofit CareerWise Colorado that's been attracting buzz. Instead of following the well-known U.S. apprenticeship model—training individuals in their 20s for careers in the construction trades—this version enrolls high school juniors to work part-time in industries including banking, health care, technology, consulting and advanced manufacturing. During the three-year program, the apprentices earn a salary while learning a skill, finishing high school and gaining college credits. They can finish with an associate degree or a professional certificate.

The combination of a tight labor market and the high cost of a college education is fueling the interest in youth apprenticeships. Unable to find employees with the necessary skills, companies are seeking unorthodox strategies to access talent.

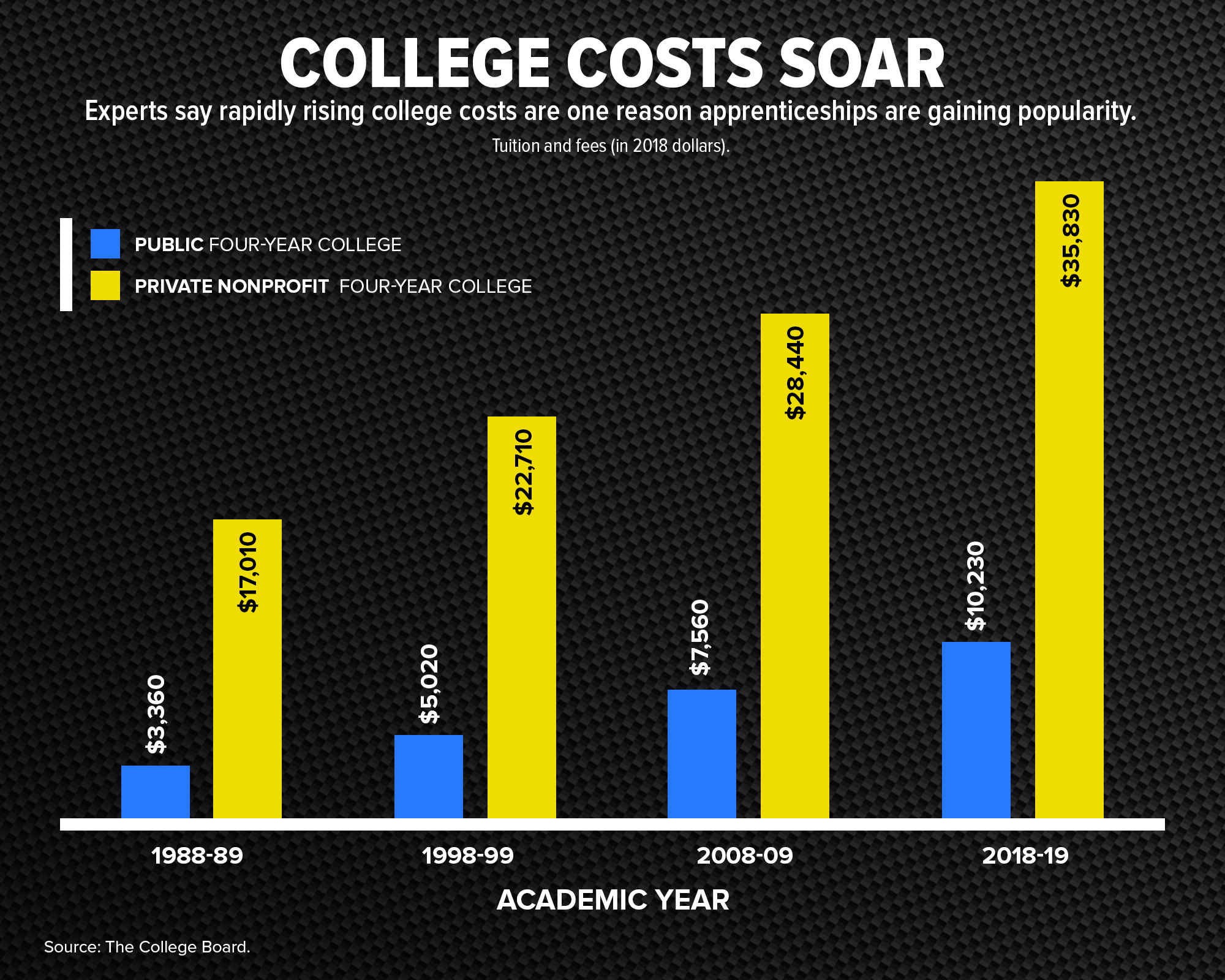

Soaring college costs are pushing high-school students to find nontraditional ways to finance a four-year degree or develop an alternate career pathway. The average annual cost of tuition and fees at a four-year private college more than doubled over the past 10 years to $35,800 while it more than tripled to $10,230 at a public university (in-state tuition), according to The College Board, a New York City-based nonprofit that creates and administers standardized tests including the SAT. And that doesn't include room and board. According to the Federal Reserve, seven out of 10 new college graduates are burdened with debt averaging $37,172.

"We really need to try something new," says John Donnelly, a vice chairman at JP Morgan Chase & Co., who also chairs the group of civic leaders that brought the CareerWise model to New York City. "A large part of the education system isn't preparing people for jobs."

And only 42 percent of students graduate college within four years. That drops to 22 percent for black students and 33 percent for Hispanic students, according to the U.S. Department of Education.

"The system is just broken," says Charles Henkels, apprenticeship director at Norco College in Norco, Calif. "The majority of kids don't stay on the track we put them on. Let's have an alternative model."

Advocates believe youth apprenticeships can be that model.

"This is a success for everybody—the companies, the apprentices, the community," says Donnelly, a former chief human resources officer at the bank and current advisor to its chairman and chief executive, Jamie Dimon. "The country needs to do this."

Advocates on Both Sides of the Aisle

Apprenticeships are a rare example of an idea with bipartisan support. Former President Barak Obama renewed interest in apprenticeships by highlighting them in his 2014 State of the Union address and poured hundreds of millions of dollars into expanding those efforts. Former Colorado governor and one-time Democratic presidential candidate John W. Hickenlooper has said that his best policy idea is replicating the CareerWise model across the country.

Two years ago, President Donald Trump said he wanted to add 4.5 million apprenticeships over five years. In June, the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) issued new proposed rules designed to create industry-regulated apprenticeships. Critics say the proposal is unclear and the programs could lack meaningful oversight. The rules are still under review and will likely change in the coming months. SHRM supports the DOL's effort to expand apprenticeships and the proposed role of employers in establishing and monitoring apprenticeship programs

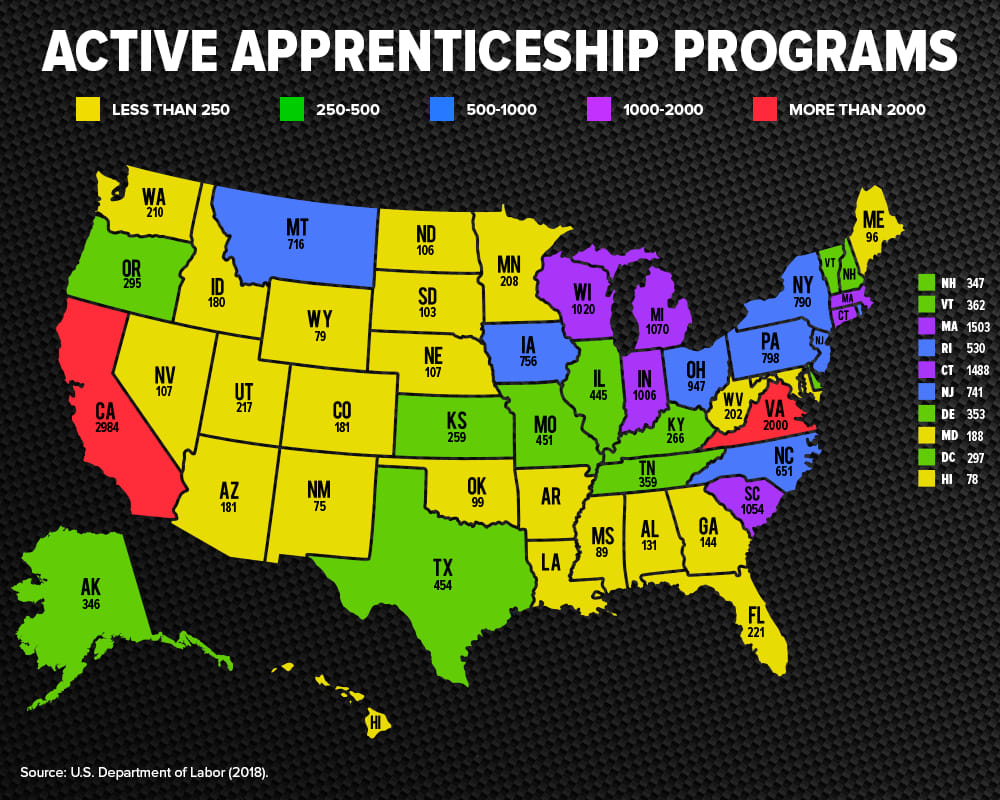

Apprenticeships in the U.S. have become more popular in recent years, as the number of individuals enrolled soared 43 percent to 585,000 from fiscal years 2014 to 2018, according to the U.S. Department of Labor. During the same period, the total number of apprenticeship programs rose 22 percent to 23,441. (The department doesn't specifically track youth apprenticeships.)

Apprenticeships differ from internships and other training programs. Apprentices must receive pay, mentoring and on-the-job training in an industry-recognized skill that's complemented by classroom coursework. State and federal programs help finance apprenticeship programs through grants and tax breaks.

A Foreign Concept

Since their creation during medieval times, apprenticeships have been a constant in Europe, especially in Switzerland and Germany. Switzerland has more than 230 approved apprenticeship occupations, and 40 percent of all companies participate in the program.

Apprenticeships never developed a strong foothold in the U.S. beyond the labor-union-driven programs that train skilled tradespeople, such as electricians and plumbers. After graduating high school, U.S. students typically go to college or to work or trade school. That two-tier system sometimes branded those not attending college as less intelligent than their peers. The stigma still lingers and is an impediment to introducing youth apprenticeship programs.

"In this country, there is a history of moving kids of a certain background off the college track," says Brent Parton, deputy director of the Center on Education and Skills at think tank New America in Washington, D.C. "You have to make sure apprenticeships are accessible to kids of disadvantaged backgrounds, but on the other hand, that you're sure they aren't just serving one type of student. It is a complicated challenge."

Students, educators and businesses must become more comfortable with the youth apprenticeships model, Parton says. "In other countries, this is in their DNA." Employers also must be willing to spend time and money developing training programs, mentors and educational opportunities for the apprentices while obeying youth labor laws.

Money is a significant barrier, Henkels says. Norco College plans to start a small pilot program with about 10 students and three employers. But at this point, there is no funding for administrative expenses, so he handles the organizational legwork as he runs the school's other apprenticeship programs.

"We are going to have to figure out how to scale up and become sustainable," Henkels says.

Competing with College

Noel Ginsberg founded the nonprofit CareerWise Colorado four years ago to organize youth apprenticeship programs because he couldn't find qualified employees for his manufacturing business. He fashioned his approach on the Swiss model where 70 percent of students choose to enter an apprenticeship after high school. Of those, 30 percent typically either stay at the company or return there after college.

"I saw it as a transformation strategy," he says.

Businesses leaders were willing to give it a try. "In Colorado, tech talent, as it is across the entire country, is hard to come by," says Tanya Jones, director of talent acquisition at Denver-based Home Advisor, which connects home owners with local service providers. "We are always looking for ways to grow our talent."

Home Advisor has been participating in the CareerWise program since it launched in 2017 and has hired a total of 17 apprentices in such areas as desktop support, coding and project management. (Ginsberg says CareerWise has placed 432 apprentices in its first three years nationally.) Jones says the students have been impressive, noting that they finished what was expected to be a 12-week orientation in just six weeks. "They are very self-motivated," Jones says, adding that she sometimes forgets they are high school students until they start talking about going to the prom. "They are very composed."

Jones says she has been disappointed by the number of students who opted to go to college full-time instead of staying for the third year. "We are losing two years of their business knowledge," she says, but "they have to make the best choice for them." The company is exploring whether introducing some incentives, such as paying for college courses, will convince more apprentices to stay for the third year.

The organizers of the Elkhart County program want more from it than just finding employees for worker-starved businesses. "In Indiana, we have brain drain," says Brian Wiebe, chief executive officer of Goshen, Ind.-based Horizon Education Alliance, the nonprofit that is the operating intermediary for CareerWise Elkhart County. "Students go to college, and they don't come back. They are done with us."

Wiebe says the hope is that apprentices will realize they can have fulfilling careers without leaving the area. The first cohort consists of 22 students working at 12 companies, though Wiebe plans to expand. "These apprenticeships have to compete with the excitement of leaving," he says.

The Appeal of NYC

New York City, another CareerWise adherent, is plenty exciting, drawing people and companies from all over the world to participate in its dynamic economy. No surprise that there is fierce competition for that talent, which is why 17 companies in the city, including Accenture and Bank of America, opted to participate in the program.

"This is a business-led initiative," says Barbara Chang, executive vice presidents of the Bronx-based nonprofit Here to Here, which launched CareerWise New York. "Businesses realized they needed to be part of the solution [to the labor shortage]. They can't sit around complaining."

As companies like Amazon, Facebook and Google increasingly expand into New York, Donnelly says finding tech talent is harder than ever and will only grow more intense.

"Getting the talent early and training them ourselves is also a big advantage," he says. We'd be able to train people and get them productive in a short period of time."

JP Morgan Chase hired 21 apprentices. Ten are tellers, while the rest are working in tech roles. Donnelly concedes that it is hard to retain tellers, though he says the bank isn't using the program just to alleviate the churn. As banks become increasingly automated, tellers are going to be required to help customers with the technology as well as offer new services to them. "We are thinking about the branch of the future," he says.

Develop Highly-Skilled Workers with Apprenticeships

Donnelly says that the apprenticeships will be invaluable to students, especially those from disadvantaged households who can't afford college and may lack connections to jobs with good long-term career opportunities.

Most of the schools participating in the New York City program are in poor neighborhoods. Chang says the nonprofit reached out to schools that were already trying to find jobs and internships for their students, believing they would be more amenable to the concept.

"This way we weren't reinventing the wheel," she says, adding that over time the program will be expanded to schools all over the city.

Rodolfo Baez is a coding apprentice at Amazon, and he couldn't be more thrilled. The 17-year-old from the Bronx says his family immigrated from the Dominican Republic 11 years ago so he and his siblings could get a better education.

"What kind of a son would I be if I didn't take advantage of these opportunities," he says. The downside? "I guess I have to give up playing video games," he answers. "I'm moving into adulthood."

Theresa Agovino is the workplace editor at SHRM.