Behavioral Economics Improve Workforce Health Decisions

Choice architecture can encourage employees to select better health plan options

Research about behavioral economics—the study of how people make choices, drawing on insights from psychology and economics—can be extremely useful in designing and communicating employee health plans.

Many health decisions that should be rational are not. In fact, irrational decisions that involve health benefits and health care are prevalent throughout peoples’ lives. The following are a few examples:

• Although children receive numerous public health messages, many young adults still become tobacco and drug users and/or obese and diabetic.

• While people understand the value of preventive health care and like the fact that many health plans now offer preventive care services without deductibles, co-payments or co-insurance, many still fail to get free health screenings or physical exams.

• Few consumers access the substantial amount of data that is available about hospital costs and mortality, readmission and hospital-acquired infection rates when they make decisions about hospitals and surgeons.

• Many people with addictions relapse into addictive behavior following lengthy periods of abstinence and sobriety.

• When some people reach age 65, they ask a friend which of the many Medicare plans to purchase instead of researching the options and making an informed decision.

In each of these examples, behavioral biases cloud rational judgment. Understanding these tendencies can help organizations redesign how they configure and communicate their health benefit plans to nudge people toward better decisions that produce better outcomes for participants and employers.

Behavioral Economics and Open Enrollment

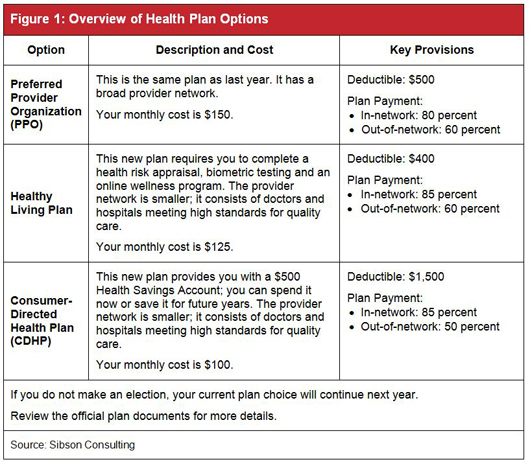

Behavioral economics can play an important part in an organization’s open enrollment process, where a key goal is to steer employees toward cost-effective health plan options. Figure 1 illustrates a simplified, typical representation of how three health plan options are communicated by organizations during annual open enrollment periods.

Although the organization wants its employees to migrate from the preferred provider organization (PPO) to the Healthy Living Plan or the consumer-directed health plan (CDHP), which have lower costs than the PPO for the employer and employees, migration is dampened by three behavioral biases:

• Loss-aversion bias. People tend to overvalue the prospect of losing something of value and to undervalue the prospect of gaining something of value.

•value system bias. People have deeply rooted value systems and selective filters. Substantial evidence to the contrary or significant influence is required before behavior changes in a way that is inconsistent with deeply held beliefs.

• Status quo bias.Inertia, or the tendency not to change, is especially significant when choices are complex.

Partly because of these behavioral biases, when the employer’s health plan participants look at the choices in Figure 1, they tend to focus on the potential loss of their current doctor-patient relationship. They stay with the PPO because they value the freedom of choice they think it offers and find the notion of restricted choice unpalatable. Moreover, the employees are inclined to undervalue the financial gains and ignore the prospect of improved quality of care available through the Healthy Living Plan and the CDHP.

How might an organization encourage its employees to choose one of the better plan options? The way those options are presented can make a big difference. There are, for example, two behavioral biases that the organization could leverage in its open enrollment materials to achieve better results:

• Clue-seeking bias. When faced with complex decisions, people look for clues, which they hope will be relevant to rational decision-making.

• Framing bias. How choices are presented has a substantial influence on the decisions people make.

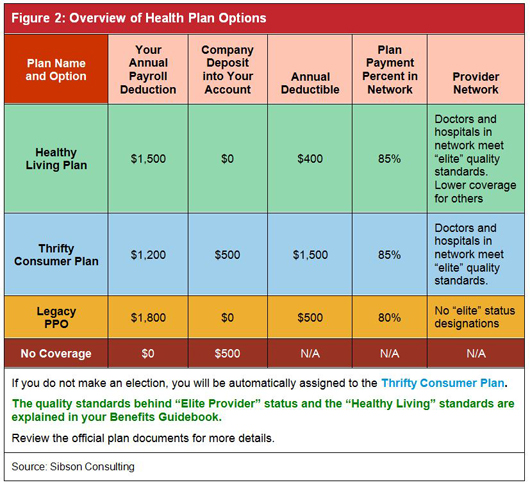

An effective technique the organization could use to encourage employees to select one of the better health plan options is known as “choice architecture”—how the various options are framed, ordered and described. People make decisions within a larger context. They look to their experiences and the environment to establish a frame of reference. Comparing Figure 2 below to Figure 1 above illustrates how the order of the options, the names of the plans, the selection of decision-making factors, the use of color and the default option can be used to influence choice.

Although Figures 1 and 2 summarize exactly the same health plan features and costs, the design in Figure 2 leverages behavioral biases to influence how people make choices. In preliminary testing with various focus groups, many people who choose the PPO Plan in Figure 1 subsequently choose the Healthy Living Plan or the Thrifty Consumer Plan when presented with the design used in Figure 2. The result is better outcomes for the employees and the organization.

Behavioral Economics and Lifestyle Changes

Behavioral economics and motivation theory can be used as well to encourage employees to make lifestyle changes that have the potential to improve their health. One increasingly popular way to do this is by using incentives to get increase participation in the organization’s wellness programs. Studies have shown that sustained quit rates for former tobacco users are three times as high among participants receiving incentives than with the control group, and when obese participants stop receiving incentive payments, many tend to regain their weight. Careful thought is required when designing wellness incentives, as they work better with some diseases than others.

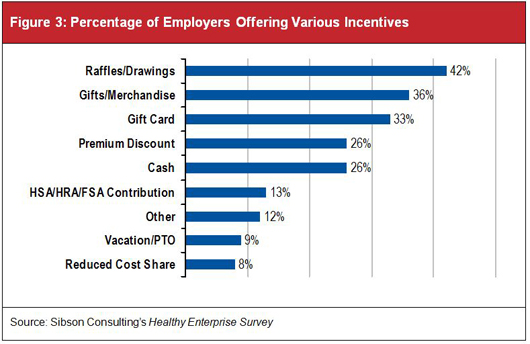

In designing a wellness program, it is important to consider the incentive’s structure, value and the requirements that people must meet to earn it. According to Sibson Consulting’s Healthy Enterprise Survey, employer-sponsored wellness programs use many types of incentives (Figure 3).

Sibson’s research found that as the incentive value increases, so does participation in an organization’s health risk assessment activities. Poorly designed incentives, however, will likely fail to achieve desired outcomes:

• If the incentive is too low, it will fail to motivate behavior change.

• If the incentive is too high, it might create a “choking” effect and impede performance.

• If the incentive is too distant, people will devalue the reward.

• If the qualifying period is too long, people will procrastinate. As the deadline nears, the perceived cost of change magnifies and people tend to give up.

• If the incentive is misguided, the reward potential crowds out intrinsic motivation by cheapening a task that might be interesting, fun or noble.

• If there are too many ways to earn an incentive, the complexity is overwhelming.

Putting Behavioral Economics to Work

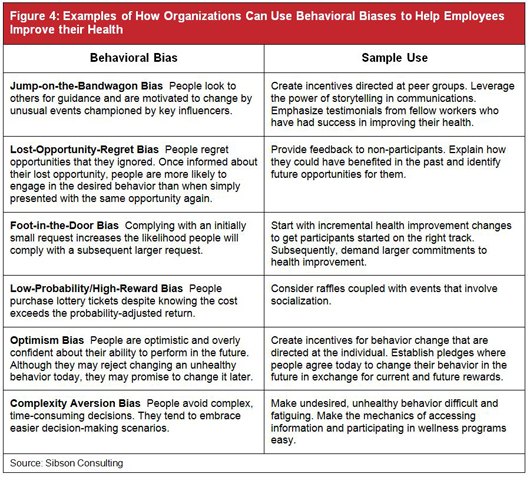

There are many ways that organizations can use behavioral economics to encourage people to take steps to improve their health. As shown in Figure 4, some behavioral biases can serve as bridges to better outcomes.

Conclusion

Despite their best intentions, people do not always make rational decisions regarding their health and their health care benefits. By using principles from behavioral economics, organizations can encourage employees to make better decisions that will improve outcomes for themselves and the organization.

Those responsible for the design and communication of health benefit plans and healthy enterprise initiatives are de facto choice architects. The ordering of options, highlighting of decision factors, naming of programs, structuring of incentives and selection of defaults are decisions made by management. Current decisions have consequences in terms of workforce behavioral bias, choice making and engagement. As an initial step toward applying behavioral economics, organizations should consider the following four steps:

• Inventory existing program designs and communicationsto assess current behavioral biases and consequences.

• Clarify the desired shifts in behaviors and decisions to achieve improved outcomes.

• Identify alternative configurationsfor program design and for reframing that will nudge participants toward better choices about benefits, consumerism and personal health.

• Estimate the costs of reframingand develop an action plan for change.

Behavioral Economics and 401(k) Plans It is no secret that most employees under-save for the day when they will stop working. Almost one-third of all U.S. workers have no savings earmarked for retirement and more than half have accumulated less than $25,000, according to a 2011 study by the Employee Benefit Research Institute. In recent years, the financial services industry has begun to deploy several behavioral economic techniques in 401(k) plans in an effort to reverse this situation. These include automatic enrollment (with which 98 percent of employees say they are satisfied), automatic contribution-escalation features and target-date funds as default options. These techniques have significantly helped solve two behavior-based problems: under-saving and poor asset allocation. |

Christopher Goldsmithis a vice president in the Cleveland office of Sibson Consulting. He has specialized expertise in health and welfare benefit plans and total compensation arrangements.

This article originally appeared in the December 2011 issues of Sibson Consulting's Perspectives, and is adapted and reposted with permission from Sibson Consulting, a division of Segal. © 2011 by The Segal Group Inc. All rights reserved.

An organization run by AI is not a futuristic concept. Such technology is already a part of many workplaces and will continue to shape the labor market and HR. Here's how employers and employees can successfully manage generative AI and other AI-powered systems.