One Year into the Pandemic, COVID-19 Fatigue Takes Hold - HR Magazine

COVID-19 restrictions are still here, leaving employers struggling to find new ways to bolster workers' spirits and mental health.

"Here Comes the Sun” was a victory anthem at Lake Success, N.Y.-based Northwell Health last year, streaming into hospital hallways whenever a desperately ill COVID-19 patient recovered enough to leave.

Not anymore.

On the one-year anniversary of the pandemic, COVID-19 cases and death tolls are still rising, and Northwell administrators fear that hearing that song will remind employees of the early days of the crisis and how long it has dragged on. Hospital staff developed mental, emotional and physical exhaustion as they treated a barrage of patients in the one-time epicenter of the pandemic that has claimed the lives of 20 of their colleagues.

Executives at the health care provider are doing whatever they can to keep employees strong as they enter year two of treating patients with the coronavirus.

“We have to be very careful about triggers,” says Maxine Cenac Carrington, deputy chief human resources officer at Northwell, which includes 19 hospitals in the New York City metro area. “How do we support them to keep going when they’re saying, ‘How do I get my heart and mind ready to do this again?’ ”

COVID-19 fatigue is a crucial problem for organizations with front-line workers. Yet trying to keep workers motivated, resilient and productive after a year of havoc that has infected every corner of their lives bedevils employers.

Stress Abounds

Seventy percent of people in the global workforce say this has been the most stressful 12 months of their lives, with 78 percent saying their mental health has been affected, according to a study by Oracle Corp., an Austin, Texas-based software company, and Workplace Intelligence, a Boston-based consulting firm. More than 80 percent of U.S. workers claim that they’re stressed. It has been an especially harrowing time for working mothers, who are trying to fulfill their work obligations while acting as de facto teachers, cooks and housecleaners. Multiple studies have shown that women are carrying more of the domestic burden than their male counterparts.

“Fear, uncertainty, loneliness, isolation, disruption—people feel like life is out of control,” says Darcy Gruttadaro, director of the Center for Workplace Mental Health at the American Psychiatric Association Foundation in Washington, D.C. “Employers are aware. They’re calling us left and right [for advice].”

Burnout, Anxiety and Depression

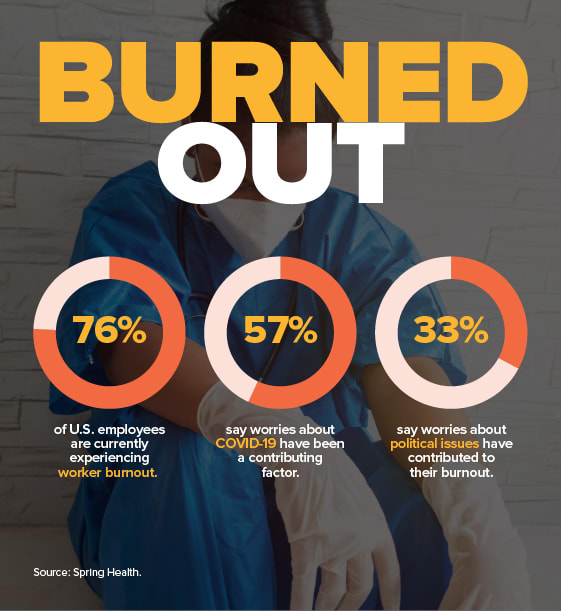

The problem is getting worse. In a survey taken in December by Limeade, a Bellevue, Wash.-based software company, nearly 75 percent of workers said they were burned out. That’s up from 42 percent at the beginning of the year.

In a separate survey, just over 40 percent of respondents said they had experienced at least one mental or behavioral health issue over the summer, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Anxiety and depression were the most common problems, and they are on the rise. Twenty-six percent of people reported symptoms of anxiety disorder, more than three times the 8 percent who said they had experienced such symptoms in the second quarter of 2019. The number of people with depressive disorder symptoms quadrupled, with one-quarter of individuals claiming to have experienced them, up from 6.5 percent in 2019.

“These numbers are alarmingly high,” Gruttadaro says.

Organizations Offer Assistance

Gruttadaro says employers are trying multiple strategies to help employees cope. Those approaches include:

- Increasing the number of free counseling sessions offered or waiving co-payments for therapy.

- Providing free access to mindfulness and meditation training.

- Checking in regularly with employees to ask about their well-being.

- Teaching managers to spot troubled employees and initiate conversations to offer help.

- Devising communication strategies to remind staff of benefits such as employee assistance programs and encouraging people to use them.

- Bolstering child care and elder care benefits.

Gruttadaro says it’s difficult to gauge the strategies’ effectiveness because so many people are reporting that they’re struggling with issues such as anxiety, stress and fatigue. “This is going to be studied for years to come,” she says.

Employees Want More

Despite some companies’ best efforts, workers say they need more. Half of respondents to the Oracle and Workplace Intelligence study said their companies added mental health services or support as benefits due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Still, 76 percent say their company should be doing more.

Even companies that have strived to protect their employees from the mental and physical effects of the pandemic are seeing signs of fatigue. Phoenix-based Sprouts Farmers Market enhanced cleaning protocols at its grocery stores, gave employees up to an additional 28 sick days, distributed bonuses, regularly communicated about its mental health benefits, and offered loans and grants to staff with financial difficulties.

Still, entire departments have either been infected or needed to quarantine after attending noncompany events together, says Alisha M. Cheek, Sprouts’ regional HR advisor for Nevada and Utah. She has learned after the fact that people came to work when they weren’t feeling well. At least one employee failed to report she was getting a COVID-19 test even though workers were instructed to inform management.

“She said, ‘I didn’t know I was supposed to tell you,’ even though we’ve told them five million times,” Cheek says. “I think after five million times, you just stop listening.”

Cheek wonders what else she can do to drive home the safety message and worries that a new approach might cause confusion. “You want to be consistent,” she says.

Jake Krug, director of total rewards for Sprouts, which operates about 370 stores nationally, says there has been a shift in employees’ attitudes. At the beginning, workers were scared and confused by the new disease. “Now they’re tired of worrying about it,” he says. “They just want it to be done.”

The end of the pandemic is getting closer, but the crisis is far from over. Experts predict that the U.S. won’t return to any kind of normalcy until at least early fall, leaving leaders to devise new ways to protect employees against burnout, anxiety and other conditions—ironic given that many organizations are better prepared to handle the virus’s next wave after everything they learned from tackling the first one.

For example, Northwell Health already hired traveling nurses to fill in for staff. In addition, there are permanent centers where staff can go for quiet time and rest. All the information about behavioral health is in one place, making it easier for employees to find. Managers have been trained to look for signs of mental health issues.

“Logistically, we’re much better prepared,” Carrington says. Yet, she adds, the search continues for different ways to help employees address the intense situation they face. The hospital has been learning how the military helps its members strengthen their psychological resolve when they must go back into battle after a stretch of civilian life.

Carrington is worried about how staff will handle another surge. She says some are optimistic about the efficacy of available vaccines. Others have expressed anger about having to relive a crisis that might have been prevented if more people had listened to experts and followed safety protocols.

“For some people, the second time could be harder,” says Dr. Heidi Levine, an emergency room physician and director of wellness and patient experience at South Shore University Hospital, part of the Northwell network. “Their emotions are already raised, so this could impact them more.”

Levine also says the slowdown in cases during the summer and fall gave staff an opportunity to regroup, though she’s not counting on that to get them through the months ahead. While she praises South Shore’s efforts to help the staff cope, Levine is starting a support group for the emergency room staff that also borrows strategies from the battlefield. “There are multiple studies that show physicians will take support from a peer before anywhere else,” she says.

Reluctance to Come Forward

Zoom meeting fatigue is common across professions, and many companies have started to limit virtual gatherings, especially happy hours and other “fun” activities designed to lift employees’ spirits. Avionos, a Chicago-based digital marketing company, stopped hosting such events last year as lethargy set in, though it still uses Zoom for business meetings. To stay connected, employees have been divided into smaller groups, giving them the freedom to decide how and when to connect.

Gibson Smith, Avionos’ chief people officer, says calling employees to chat is one of the most effective ways to determine employees’ mental health status. He says he calls about two employees a day to check in. Managers also regularly touch base with their teams for conversations that transcend work-related topics.

“Ask direct questions,” Smith advises. “Ask if they’re struggling. Direct contact is paramount.”

Some employees won’t be forthcoming about their issues, fearing they might appear weak or unprofessional.

Erin Hernandez has had two new bosses since the pandemic began and didn’t feel comfortable talking about her anxiety with people she barely knew. “There’s an underlying concern about getting a new manager who doesn’t know me or my work,” says the Atlanta resident who is a data analyst for U.K.-based InterContinental Hotels Group. “Developing a rapport virtually is already a challenge.”

She was especially worried because her work slipped in the early days of the pandemic as she buckled under the pressure of working from home with her husband while caring for her 6-year-old daughter. That challenge was compounded by a 35 percent reduction in her family’s earnings because of pay cuts and her husband’s reduced work schedule.

“I was crying all the time,” Hernandez says. “I’d wake up in the middle of the night and stay awake for hours thinking about whether someone [I know] is going to get sick [with COVID-19].”

Hernandez opted to see a therapist but says her options were limited through the insurance she receives from her husband’s employer. She pays $150 a session out of pocket to see a therapist every other week.

“We’re burning through dollars,” she says. “But it’s a lot to be with people 24/7 with no escape.”

Theresa Agovino is the workplace editor for SHRM.

Illustration by Adolfo Valle for HR Magazine.