What Matters to Hourly Workers

Many hourly workers are feeling uneasy. To retain them, employers should focus on the basics.

If the constant scramble to fill shifts and the growing threat of strikes aren’t enough to cause employers headaches, here’s another problem that could keep them up at night: Nearly half of hourly workers are searching for another job, according to a new survey report from SHRM, titled Understanding Hourly Workers: Motivations, Expectations and Experiences.

That’s an alarming statistic, says Kyle Holm, vice president, compensation advisory, at Sequoia Group, a San Mateo, Calif., consulting firm that specializes in benefits and compensation. “That number is just not sustainable,” Holm says, because employers need to have experienced workers on hand.

Stagnant wages are one factor forcing hourly workers to switch jobs. Many hourly employees also are in entry-level and more-junior positions, so they’re less established and more likely to be thinking of leaving, Holm says. He thinks workers don’t really want to take on the stress of starting fresh somewhere else, but “[y]ou do because you feel like you have to if your prospects are not great with where you’re at.”

The turbulence among hourly workers is driven by multiple factors, including a lack of significant pay increases in recent years, a tight labor market that gives employees the option to jump ship and get paid more elsewhere, and the push by younger generations for better work/life balance.

Money, Money, Money

The buying power of hourly workers has been stagnant for decades. When adjusted for inflation, the median hourly wage was $22.88 in 2022, compared with $21.90 in 2002, according to the Economic Policy Institute. And 67 percent of hourly workers have a household income below the national median of $70,000, the SHRM survey points out.

“Employers wonder why these people go someplace else for 50 cents more an hour. It’s because if they stay loyal to the company, all they get is a 2.5 percent pay increase and they can never better their lives,” says Cara Silletto, president and chief retention officer at Magnet Culture, a Louisville, Ky., leadership development company that trains managers. She specializes in helping companies with low-wage front-line hourly workers.

As inflation has contributed to higher prices for groceries, gas and other needs, hourly workers are feeling the pinch.

Companies that don’t invest in pay and benefits will fail, Silletto says. “You can’t neglect making yourself a great place to work,” she says.

Holm says last year’s United Auto Workers strike is symptomatic of hourly workers’ desire to have more economic stability and to make up ground on pay they feel they’ve lost in recent years.

“It’s definitely about the money now,” he says.

The SHRM survey found that 73 percent of hourly workers would stay in their current job for a higher wage. Of those workers, 28 percent would consider staying if they got a pay increase of less than 5 percent, according to the survey of 2,000 hourly workers conducted April 6-May 9, 2023.

Derrick Scheetz, a SHRM senior researcher, says some businesses that are nervous about talk of a recession have tightened budgets.

Companies can pair the survey data with their own exit interviews and other metrics to figure out whether raising hourly wages is an “obvious solution,” Scheetz says.

Despite the marketplace push toward more pay transparency, Holm says not everyone should be paid the same.

“We’re kind of at that point where companies are starting to realize when you have a top performer, the cost of turnover far exceeds the increase that it would take to keep them,” he says.

That means managers need to be trained to identify and develop top-performing employees. “The manager should be the eyes and ears for the organization on any retention risks and should be able to identify where a company should make their investments,” Holm says. “Are you proactive in making sure that you keep your key employees, or, you know, do you just have a peanut butter policy that you’re applying across the board and not looking more into the individuals?”

Transparency About Pay, Expectations Is a Must

Today’s persistently competitive labor market means hourly workers can easily find somewhere else to work. And since job comparison data is widely available now on sites such as Glassdoor, workers can uncover inequities if they’re not paid fairly in relation to others.

‘Every new hire is a flight risk.’

Cara Silletto

Fair pay is a principal expectation for employees, Scheetz says, with roughly one-fourth of hourly workers saying that’s a key responsibility of employers.

Younger generations in particular are demanding transparency and fairness, Silletto says. Many younger workers, and older workers too, have the confidence and risk tolerance to leave for better opportunities, she points out: “Every new hire is a flight risk.”

On the employer side, successful companies are transparent about what they expect. Workers who start a new job and find it doesn’t match the advertised description often aren’t going to stick around.

In-N-Out Burger is revered by some for paying workers well above prevailing wages if they’re aligned with the fast-food chain’s mission, Holm says. In-N-Out also is transparent about what it expects from workers, down to how its potatoes are cut, he says.

Flexibility and Generation Z

The pandemic laid bare the striking differences between front-line hourly workers and the executives who run their companies. As many higher-level managers have continued to work remotely at least part of the time, that option has not been available to lower-level employees.

“A lot of senior leaders and executives have become quite disconnected from the reality of our front-line workers,” Silletto says.

Those realities include not just financial struggles but a lack of flexibility, such as the chance to go watch their child’s afternoon kindergarten program or to work from home on a snow day.

Silletto sees downsides to systems that distribute shifts, work assignments and equipment based on seniority because newer workers get the “leftovers,” despite being the biggest flight risks. “The current staff will treat the new hires poorly—it’s like a new version of hazing,” she says. Managers need to be trained to nip that behavior in the bud, she notes, as they often have the biggest impact on whether workers stay or go.

Companies also need to put more effort into onboarding—and not just for the first few days. Silletto says this should include checking in with new hires every few shifts as they settle in. It can also mean providing chances for advancement sooner for new workers who quickly learn new skills.

The pandemic also reset how workers think about work’s place in their lives and how they want to be treated. Silletto regularly hears employees complain about the lack of personal regard from managers. “I’d prefer to be called by my name, not my trucker number” is one example.

A full 90 percent of hourly workers said knowing their workplace cares about them is important, the SHRM survey found. Having that knowledge will inspire workers to be more productive, Scheetz says.

Ideally, employers are “doing what’s best for their workers, who in turn would do good work for them and what they’re assigned to,” he explains.

In addition, workplace culture is especially important to younger generations of hourly workers, according to the SHRM study. While just 22 percent of Baby Boomers and Traditionalists said culture was a factor in deciding to remain in their jobs, the figure was 39 percent for Gen Z and younger Millennials.

Scheetz says that may be because younger, less-experienced workers feel the brunt of bad management and have less clout to address problems with company culture. Not surprisingly, those younger generations are also the most likely to be searching for a job—60 percent of them, compared with 46 percent for the hourly workforce overall, the SHRM study found.

Flexing Their Schedules

For hourly workers, a big part of workplace culture is scheduling.

In the wake of the pandemic, many hourly workers returned to front-line jobs and didn’t have the option of working from home that salaried employees did, Holm says. “There are mental health consequences to what feels like an enormous amount of pressure on a job that many times doesn’t even pay for the basics,” he says. “Companies are becoming increasingly aware that that anxiety … will impact performance and will always be a huge, huge contributor to turnover.”

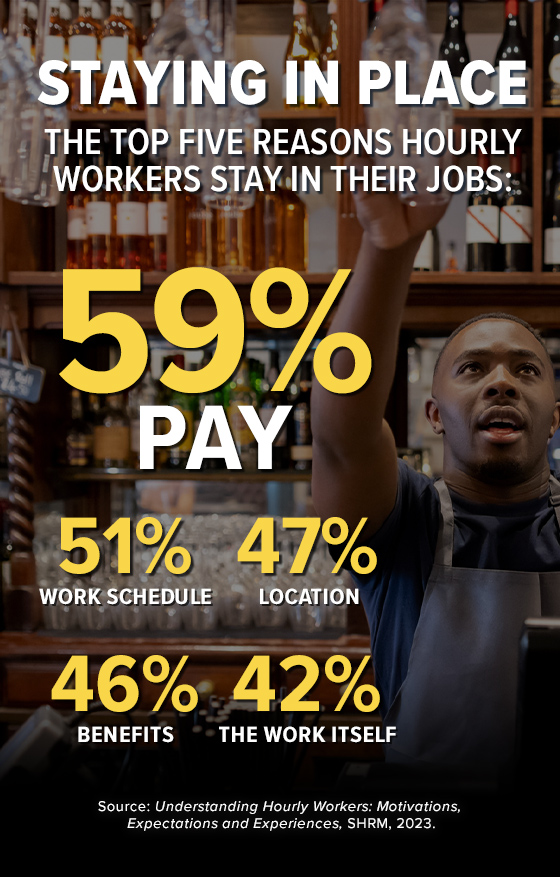

For the 51 percent of workers who say work schedules are important to making them want to stay on the job, companies are coming up with some creative approaches, Silletto says. Some offer “pods” that workers can choose from. One pod might have schedules set a month in advance for those who want predictability, and another might be for those with another job who don’t want to be committed to a schedule too far in advance.

“I’m seeing an uptick in creative scheduling,” Silletto says. She notes that some workers want to be home for dinner with their families, so the second shift is proving harder to fill than the overnight shift, leading companies to pay more for those hours. “We have to get into the mindset of the workforce,” she says.

And younger workers bring a mindset that prioritizes more than work.

Tim Chatfield is CEO and co-founder of Jitjatjo, a New York City tech company whose virtual marketplace matches workers and companies in the hospitality and retail industries.

“The employee value proposition has shifted substantially,” he says. Gen Z workers, he notes, are outspoken about what they want to get out of work. And by 2025, 75 percent of the global workforce will be Millennials or Generation Zers, according to estimates from consulting company Deloitte.

“There’s a shift toward flexibility,” Chatfield says, adding that companies want a more agile workforce. “The workforce … is putting a higher priority on their own schedule, in terms of, ‘These are my life priorities.’ Pre-COVID, people were fitting their life around work. I think that has changed. Which could also be said that there’s a shift in loyalty, from the employer to my own personal schedule and bank balance.”

‘Among hourly workers, the basics matter.’

Derrick Scheetz

Chatfield expects companies to increasingly use talent marketplaces both for hiring outside workers and for deploying in-house workers. He also anticipates that more workers will move back and forth between freelance and staff jobs.

“We’re seeing people crave flexibility, to the point that it’s encouraging them to … leave the safety of a static schedule to get the flexibility that they crave,” Chatfield says.

So how do companies avoid the recruitment and training costs of turnover churn?

“Among hourly workers, the basics matter,” Scheetz says. Those include good pay, pay equity, preferred schedules, transparency, respectful treatment and a sense that the company cares about its people.

The good news for employers? “None of this is rocket science or difficult to do,” Silletto says.

Tamara Lytle is a freelance writer in the Washington, D.C., area.

Explore Further

SHRM provides business leaders with information and resources to help keep their organizations’ hourly workers on board.

Starbucks Boosting Wages in 2024

Starbucks is raising wages for most of its hourly employees by at least 3 percent and enhancing other benefits this year in a bid to stay competitive, the company announced.

Instant Pay Benefits Booming in Popularity Among Gen Z Workers

Instant pay benefits have become more popular in recent years, allowing employees to withdraw money directly from their paycheck ahead of their designated payday in exchange for a small fee.

New York State’s New Pay Transparency Law In Effect

Under New York’s new law on pay transparency, which took effect last year, employers in the state with at least four workers must include an hourly rate, salary or pay range for all advertised jobs and promotions.

The Plight of Front-Line Workers

Little pay, long hours and a lack of career prospects have hindered the professional advancement of millions of front-line workers.

Bringing Compensation Up-to-Date

Six steps for employers to improve their footing in a shifting compensation landscape.