Organizations’ employment and salary actions can create the unintended perception that pay is distributed unfairly, which can have undesirable consequences. Consider the not uncommon instance of a 10-year, high-performing employee who decides to start looking for a new job after learning that a new colleague—who has a great deal of potential and enthusiasm but little relevant experience and whom she has been asked to train in the same role—has been hired at her pay level.

This example illustrates one form of salary compression: when the pay of one or more employees is very close to the pay of more experienced employees in the same job. There is another form of salary compression: when employees in lower-level jobs are paid almost as much as their colleagues in higher-level jobs, including managerial positions.

When salary compression and the policies that enable it are sustained over several years, it can be demoralizing and lead to widespread dissatisfaction. Employers should be concerned because salary compression transforms the organization’s single largest cost (i.e., compensation) from a motivator into a “demotivator.”

Moreover, while salary compression is not illegal, it is often accompanied by pay inequities that could violate equal pay laws. In situations where salary compression causes salary inversion—where newer staff make more than experienced staff—it could create a pay equity problem if the experienced staff are a protected class.

This article looks at how organizations can determine if they are experiencing salary compression. Moreover, because this problem is more costly to fix than it is to prevent, we explore what organizations can do to avoid future salary compression.

What Causes Salary Compression?

Salary compression has many causes:

|

How to Tell if Salary Compression Exists

Two straightforward but effective analyses can determine if an organization is experiencing salary compression and can help identify specific areas of concern that warrant a closer look:

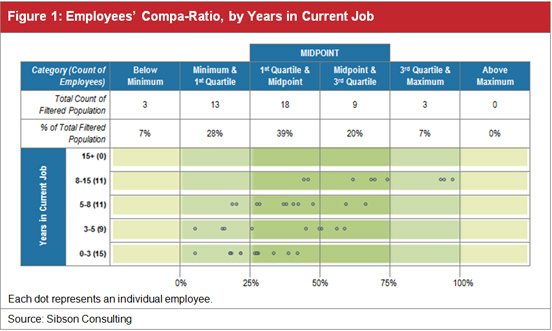

• Review the compa-ratios within each salary grade or band by the employees’ time in position. While time in a position is not the only factor that moves an employee through a salary range, it is a good proxy to start testing for compression within a specific salary grade or band. When shorter-service employees appear deeper in the range (e.g., the third or fourth quartiles) and longer-service employees appear at the beginning of the range (e.g., the first and second quartiles), it is a sign for closer examination. Note: An internal compa-ratio identifies the relationship of an incumbent’s salary relative to the salary range midpoint. It is calculated as the employee's current salary divided by the salary range midpoint for the job the employee occupies.

(click on figure to view larger version)

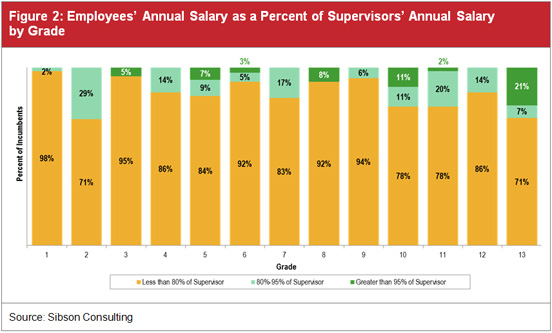

• Analyze how supervisors’ salaries compare to their direct reports’ salaries. While there is no rule for when the salary-compression level becomes dangerously close, a good rule of thumb is to look at areas where direct reports’ salaries are more than 95 percent of supervisors’ salaries. Areas where direct reports’ salaries are 80 to 95 percent of supervisors’ salaries should be watched carefully for changes that could cause salaries to exceed 95 percent.

(click on figure to view larger version)

Most organizations should conduct an analysis annually to monitor the severity of salary compression. Those that have more severe issues, concerns about compression or high turnover rates or do a great deal of hiring may need to conduct an analysis every six months.

Preventing Future Salary Compression

Although some actions, like low annual raises, reorganizations and other events are effectively beyond HR’s control, there are steps that can limit the detrimental effects of salary compression. For instance, when a new job opens, organizations should try to promote someone from within, rather than hiring from the outside. It that is not possible, it is important to:

• Look for high-potential external candidates who are ready to move up into the job and will see it as a promotion. This will limit the organization’s need to pay the new hire a premium.

• Control pay both from an HR policy standpoint and from a budgetary standpoint. Managers will usually want the more experienced but higher-cost candidate if there is no policy or cost constraint dictating otherwise.

• Limit how high within a range new hires can be paid. Although HR policies that do so are generally unpopular and thought to be contrary to an organization’s goal to “hire the best talent,” many effective organizations have such policies.

• Require a review of equity adjustments for incumbents if new hires are brought in at higher salaries. This can encourage managers to think hard about how important prior experience in the same job really is.

Another cause of salary compression that an organization can control occurs when one organizational unit is relatively liberal with salary increases and promotions and other parts of the organization that have the same jobs are not. Strategies to control this include:

• Institute transparency across units, either before or even after compensation actions are taken. In cases where there has been little or no transparency over several years, the disparate actions between different organizational units can create salary compression and other inequities. Transparency can take the form of a simple scorecard showing the rates of increases and promotions in each unit. This tends to create a norm and, over time, leads to decisions that are more consistent and responsible.

• Institute calibration across units. Calibration can involve managers sharing planned compensation actions with their peer managers. It can also include several levels of approval for any actions before they take place so that a senior leader can spot any actions that appear suspect and will cause inequities, including compression.

Conclusion

The essence of compression is a failure of organizations to make meaningful distinctions among employees and differentially recognize what people are due. Consequently, salary compression can be a serious problem that eventually causes an organization to lose some of its most talented employees. Although many organizations have unintentionally allowed salary compression to take root, there are actions they can take now and in the future to keep it from reoccurring.

Jim Kochanski is a senior vice president for Sibson Consulting and leader of the performance and rewards practice. He develops approaches and methods to help organizations align expectations and rewards to improve performance. Yelena Stiles is a senior consultant for Sibson Consulting. She specializes in compensation and performance management program assessment, redesign and implementation.

This article originally appeared in the July 2013 issue of Sibson Consulting's Perspectives and is reposted with permission from Sibson Consulting, a division of Segal. © 2013 by The Segal Group Inc. All rights reserved.

Related SHRM Articles:

Keeping Salary Administration Programs Current, SHRM Online Compensation, June 2013

Updating Salary Structure: When, Why and How?, SHRM Online Compensation, May 2013

An organization run by AI is not a futuristic concept. Such technology is already a part of many workplaces and will continue to shape the labor market and HR. Here's how employers and employees can successfully manage generative AI and other AI-powered systems.