Although many organizations struggle to find money to differentiate base pay increases or bonuses for high performers, other companies with similar budgets and performance are able to distinguish between high and average performers in compensation. They do so by "carving out" a portion of the pay increase or variable pay/bonus budget for employees who are designated as high performers. Using this approach can help organizations live up to their aspirations to truly pay for performance and avoid creating an expensive and ineffective entitlement mindset about pay.

What Are Compensation Carve-Outs?

The carve-out approach reserves a portion of the compensation increase budget for the highest performing employees. A number of organizations have implemented programs under which, for example, they reserve 0.5 percent of their 3 percent overall merit pay budget for their top performing employees. They then divide that money among the top performers in addition to the 2.5 percent that is allocated to all employees who are average or high performers.

Although the number of employees who are deemed high performers will have a significant impact on the extra amount they get, even with a modest carve-out and a reasonable number of high performers, the carve-out approach can provide them with noticeably higher rewards.

The carve-out approach works because it changes the dynamics at several points in the pay determination process: budgeting, communicating and setting expectations, evaluating performance and delivering differentiated rewards.

Budgeting

Although senior leaders at most organizations want managers to differentiate pay raises and bonuses among low-, average- and high-performing employees, the manner in which the budget for pay increases is set and communicated often sabotages this goal. If the merit or base pay increase budget is set at and communicated as 3 percent, most employees will expect to get at least that much. Such expectations are impossible to realize unless the number of low performers (who get no raise) is the same as the number of high performers (who get more than 3 percent), which rarely happens.

Moreover, once an expectation has been set, managers will try to disappoint as few employees as possible, which usually results in everyone receiving essentially the same increase.

The same budgeting principle holds for bonus pools. Some organizations set a target bonus for the year and then express the actual bonus or incentive as a "percent of target" (i.e., 110 percent of target). Once that number is communicated, it creates an expectation among all employees that managers find difficult to meet.

In organizations that use the carve-out approach, a portion of the bonus pool budget is set aside for high performers. For example, if the overall bonus is 110 percent of target and the organization wants to give high performers more than that, the carve-out might be 10 percent. While average performers would receive approximately 100 percent of target, high performers would receive more.

Determining how much to carve out is an important leadership decision. Organizations tell us it should be based on how difficult it is for employees to meet their goals and the percentage of the workforce they expect to designate as high performers.

An organization's culture often dictates the appropriate level of differentiation. In some organizations, the norm is to have a very small percentage of employees defined as high performers because of very difficult goals or high performance standards. Only 5 to 10 percent of employees might be rated as high performers. These organizations can use a smaller carve-out than organizations where 20 to 30 percent of employees are rated high performers. If more than 30 percent of employees are rated high performers, even a relatively large carve-out will yield only modest pay differentiation.

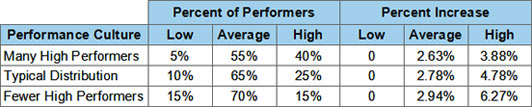

The table below illustrates how the percentage of employees designated as high performers might affect the percent increase they receive. It assumes an overall 3 percent budget for pay increases with a 0.5 percent carve-out for high performers. For example, an organization in which 40 percent of the employees are designated as high performers would be able to give them a 3.88 percent average increase while an organization in which only 15 percent of the employees are designated as high performers would be able to give them an average increase of 6.27 percent.;

Increase Percentages in Three Performance Cultures

Source: Sibson Consulting. |

Although an organization can estimate the size of the carve-out in its original budget for the year, it may increase or decrease its size, just as it may increase or decrease the merit or bonus pool, before it makes awards.

Communicating and Setting Expectations

Organizations say that how they communicate the size of its merit or incentive budget is an important component of the carve-out approach. While many organizations do not announce this information formally, often it is communicated to employees informally. If this is the case, it is best to divide the budget into two parts:

- What employees will get on average.

- The portion reserved for high performers.

Organizations have found, however, that if they make a formal communication about the salary increase or bonus budget, it is best to announce what employees can expect to get on average. This will set the appropriate expectation among the majority of employees and increase the chance that high performers will feel recognized properly if they receive more than average.

Sibson has been asked if this approach to communicating what employees will get on average, rather than the entire budget, is candid. Its response is that setting realistic expectations is the most straightforward way to communicate with employees.

Experience has shown that another aspect of being honest with employees is to communicate clearly that budgeting a certain amount for the year for compensation increases, bonuses and promotions does not mean that it all will be spent. In the past, managers in many organizations tried to spend all the money budgeted, or more. In recent years, however, some organizations have realized that compensation costs should be managed just like other budget items. They spend only what can be justified by performance and supported by business results. Most organizations still need to work on communicating this point.

Evaluating Performance

Organizations that use the carve-out approach have discovered that it can be used with any performance management program and with any type of goal setting, rating scale and performance feedback method. It tends to reduce the gaming of performance ratings that can occur when managers try to get a desired level of compensation for their employees. For example, organizations have found that managers who know that a specific percentage of the pay increase budget is set aside for high performers will be less likely to inflate the ratings to try to get more for their staff as a whole.

Although carve-outs can be used with any type of performance rating scale, organizations that use micro differences—ratings with fractional numbers (for example, 3.6, 3.7 and 3.8)—say the program becomes difficult to administer. Some have told us that if they do use micro differences, they should be clustered together for rewards purposes. For example, 3.6 to 4.4 could be a cluster on a 5-point scale. If micro differences are not clustered, the organization might be inclined to calculate merit increases in micro increments (i.e., 2.8 percent and 2.9 percent) with differences that are so slight that they imply a false precision without providing meaningful differentiation. In this situation, we recommend using whole number ratings before applying the carve-out concept and determining increases or variable payouts.

Delivering Differentiated Rewards

Some organizations create worksheets for managers to make recommendations about base pay increases and bonuses. Others collect the performance ratings and calculate centrally what the appropriate rewards should be. If the worksheet approach is used, there is usually a guideline matrix that accompanies the worksheet or is imbedded into it to help managers differentiate pay but stay within the overall budget.

One perceived criticism of the carve-out approach is that as the number of high performers increases, each one receives less money. This is, however, true with or without carve-outs. We have seen organizations where as many as 50 percent of the employees are rated as high performers, and unless there is an unlimited pay increase or variable pay/bonus budget, a high number of high performers will drive down the amount each one can get. The exception is in commission-based plans that are tied directly to revenue, such as those for sales people. For most other types of employees, however, there is usually a limited budget or at least a cap on the amount that can be spent, even in the best year.

In one high-performing organization, a manager said that “only 5 to 10 percent of our employees are rated as high performers, so there is no dispute about who they are and about them giving more.” In organizations where 30 to 40 percent of employees are rated high performers, however, there always seem to be even more people who can meet the standard. The solution is to decide in advance how much an organization wants to pay for performance and what the definition of high performance is.

This shared standard and definition will be critical at the moment of truth, when a manager gives an employee his or her performance rating and reward. Unfortunately, this part of the process is not easy for most managers, who tend to say things like “if it were up to me, I would give you more.”

By helping employees set more realistic expectations, the carve-out approach can help managers be more comfortable communicating accurate messages. The message for the majority of employees will be “your performance was good, and you are getting the target rewards.” For the smaller group of high performers the message will be “your performance was outstanding, and your rewards are above target.” The carve-out approach can help managers deliver both of these messages with confidence.

Conclusion

For organizations that are serious about paying for performance, the carve-out approach can be a viable way to overcome some of the perceived barriers that can result from limited compensation budgets and unrealistic employee expectations. However, the steps of budgeting, communicating, setting expectations, evaluating performance and delivering differentiated rewards takes work and commitment from the organization and its managers and leaders.

Jim Kochanski is a senior vice president in the Raleigh office of Sibson Consulting. As the leader of Sibson's Performance and Rewards Practice, he develops approaches and methods to help organizations improve performance, upgrade talent and connect performance and rewards.

Robin Kegerise is a consultant in the Raleigh office of Sibson Consulting. She specializes in developing compensation strategies and structures for executives and non-executives.

This article is adapted and reposted with permission from Sibson Consulting, a division of Segal.

© 2011 by The Segal Group Inc. All rights reserved.

Related SHRM Video:

Focus on HR's host Kathleen Koch speaks to Jim Kochanski and John Rubino about some of the issues today's compensation systems have and advice on how to address them.

An organization run by AI is not a futuristic concept. Such technology is already a part of many workplaces and will continue to shape the labor market and HR. Here's how employers and employees can successfully manage generative AI and other AI-powered systems.