We’re hearing a lot lately about the disappointment and frustration of performance reviews. At Confirm, we run performance cycles for our customers every day.

We’ve learned that:

- How we work isn't how we're measured

- Employee performance follows a power law, not a bell curve

- Calibrations make bad manager ratings worse

How we work isn’t how we’re measured

After World War I, industrial psychologist Walter Scott introduced a consistent rating scale for the U.S. military to evaluate recruits. In the 1920s, this model was brought into the workplace, and the manager review was born.

Back then, work was repetitive and solitary. And managers had near-perfect visibility into the work their staff were doing.

In the 1930s, Nazi military psychologists found that incorporating peer feedback led to better officer selection. This method was adapted for American workplaces in the 1950s, ultimately becoming the 360° review.

We’re still using these old methods to measure performance. But the way we work has changed. Today, anyone can log into Slack or Teams and message anyone else in the company. We form cross-functional teams to solve a problem. We connect from all over the world using Zoom and Webex.

We work in networks. But we still evaluate work in hierarchies.

In the new world of work, the number of an employee’s touchpoints has gone up, but their manager’s visibility has gone down. Remote work makes it hard for managers to know what’s really going on. Zoom and Slack obscure conversations that used to happen in the open.

How do we solve this? An approach called Organizational Network Analysis (ONA) provides a quantitative view of performance based on every employee’s view of one another. ONA allows companies to measure performance in the way it really happens: through networks.

In our reviews, we find that top performers impact dozens of their coworkers. Not just their managers or the three or four peers who contribute to a 360° review. And that impact cuts across job functions, levels, and geographies.

Traditional performance reviews weren’t built for this world of work. The more networked our jobs become, the more broken traditional performance reviews will feel.

Employee performance follows a power law, not a bell curve

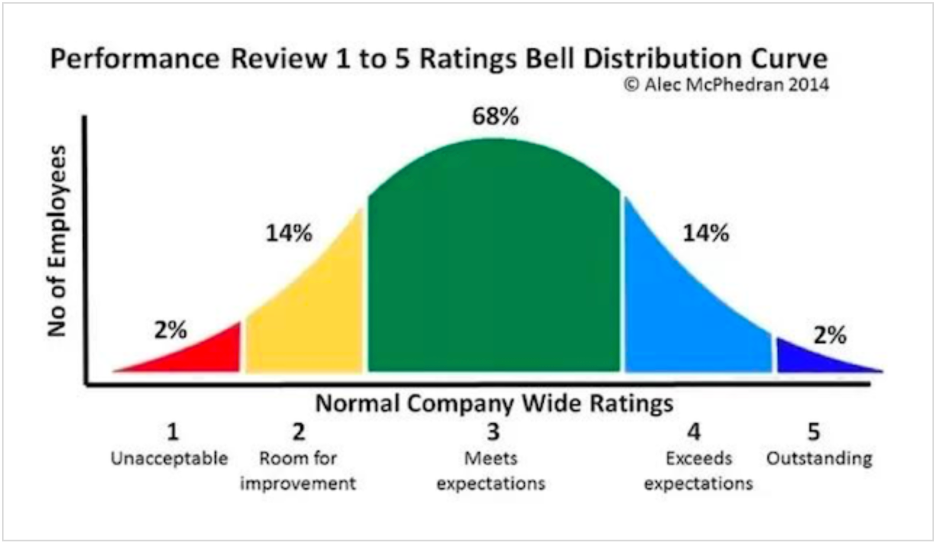

When companies run traditional performance cycles, they produce normally distributed bell curves of manager ratings. A bell curve is what you’d expect to find when the underlying variables you’re measuring don’t affect each other. For example, the distribution of height, or IQ.

In early performance reviews, a normal distribution made sense. Employees only interacted with a supervisor and a few coworkers. Work was repetitive and solitary. So, most workers became “average,” with tails of above and below-average performers on either side.

In every performance cycle we’ve run at Confirm, we see employee performance follow a power law rather than a bell curve. Not just at the org level—within teams and job functions, too. It means that a small number of employees are driving disproportionate impact.

Since we now work in networks, this distribution is no surprise. The employees in the network affect one another. Work isn’t solitary anymore. There’s a lot of variability in how employees plan a marketing campaign or design a new software feature.

Bill Gates understood this. He once said: “A great lathe operator commands several times the wage of an average lathe operator. But a great writer of software is worth 10,000 times the price of an average software writer.”

But most companies are stuck in the industrial past. So they squash the power law into a bell curve. The 10,000x employees that Bill Gates talked about will appear merely above average. And the impact of underperformers becomes overestimated.

But which top performers will get squashed down? That question will be answered using another broken practice: calibration.

Calibrations make bad manager ratings worse

If you’ve ever wondered why terrible performers hang on while top performers go unrecognized, calibration is often the answer.

During calibrations, managers meet to compare their proposed employee ratings with other managers. Conceptually, ratings are adjusted with the goal of creating consistency across the organization. But in practice, calibrations often defer to the loudest or highest-ranking manager in the room. They introduce bias and reward politics.

But the real problem is what companies are calibrating against: a bell curve. And the only data they have to calibrate biased manager ratings to are other biased manager ratings.

ONA offers a new baseline to calibrate against—one built from every employee’s view of one another. And the network around an employee sometimes has a different opinion than their manager.

In this real example, Tracy and Michael are doing the same job. Tracy is performing exceptionally well according to dozens of people around her. But the company had too many employees “Exceeding Expectations,” and not enough available promotions. So, she was calibrated down to the same “Meets Expectations” rating that Michael got from a different manager.

From manager ratings alone, you might think Tracy and Michael are equivalent. They’ll receive the same merit compensation and development opportunities. But the ONA data from Confirm says that Tracy and Michael are completely different performers.

How often does this happen? Our research shows that managers over or underestimate their employee’s performance nearly half the time. Academic research suggests that more than 60% of a performance rating can be attributed solely to the idiosyncrasies of the manager.

If you were Tracy, you might wonder, “What do I need to do to get ahead?” Sadly, for many unrecognized top performers, the answer is simple: leave.

What’s next for performance reviews?

We used to hear about the death of performance reviews. They were supposed to be replaced by “continuous feedback” and “career pathing.”

Those are both great. But they don’t help leaders struggling to decide who to promote or PIP. Only good performance measurement can do that. And Organizational Network Analysis is the science behind it.

As HR practitioners, we owe it to the people we serve. The status quo deserves a PIP.

WRITTEN BY

Josh Merrill

Co-founder and CEO, Confirm and David Murray, Co-founder and President, Confirm

SHRM Labs, powered by SHRM, is inspiring innovation to create better workplace technologies that solve today’s most pressing workplace challenges. We are SHRM’s workplace innovation and venture capital arm. We are Leaders, Innovators, Strategic Partners, and Investors that create better workplaces and solve challenges related to the future of work. We put the power of SHRM behind the next generation of workplace technology.