How to Recognize—and Avoid—Caregiver Discrimination

Family responsibilities discrimination cases are on the rise—and the odds aren't in employers' favor.

Introduction

Arriving home after a tiring business trip, Ava Sloane barely had time to open her mail when her brother called to tell her that their 85-year-old mother, a widow who lived alone in a retirement community, had fallen and needed help.

Arriving home after a tiring business trip, Ava Sloane barely had time to open her mail when her brother called to tell her that their 85-year-old mother, a widow who lived alone in a retirement community, had fallen and needed help.

“I was on a plane to Florida the next day,” says Sloane, a recruiter for global consultant Deloitte in Hoboken, N.J.

The fall marked the start of her mother’s physical and mental decline. Over the next nine years, Sloane made countless trips to help with her mother’s increasingly frequent health emergencies, often with little advance notice.

“One thing my parents never envisioned when they moved to Florida is that they were actually going to age,” she joked. “They thought it would all be poolside fun.”

Of course, parents get old—and they often rely on family members for help when their health deteriorates. And children, spouses and other family members get sick, as well, all of which can take a toll on the well-being of caregivers and their ability to do their jobs successfully, if at all. Concern for employees in these types of situations is what led Deloitte—along with a small but growing number of other companies—to offer paid leave to family caregivers.

Sloane, one of the first Deloitte employees to use the benefit, spent most of her caregiver leave in Florida taking her mother to see doctors, coordinating around-the-clock care and stepping in when aides needed a break.

Making allowances for caregivers is likely to become more important for HR leaders who want to lure talented workers. AARP projects that 40 million U.S. adults currently provide critical support to family members with a chronic, disabling or otherwise serious health condition. And that number is likely to rise as the population ages. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, by the year 2030, 1 in 5 individuals will be ages 65 and older.

At the same time, members of the Millennial generation are starting families of their own. Over 1 million women in this age bracket are having babies each year, according to Pew. And since Millennials are generally opting to have children later in life than did previous generations, many may find themselves stretched thin as they look after the needs of both older parents and young kids.

There are also legal risks for employers who neglect to recognize the plight of caregivers or who treat caregiver employees differently from other employees. A growing number of workers are winning lawsuits claiming that their bosses have discriminated against them based on their family responsibilities.

The details of some of these cases are troubling. For example:

- A female employee was told it was “too bad” she got pregnant after the promotion that had been promised her was given to a man.

- After applying for a position, a father was told that the job had been “specifically designed for single males without children.”

- A woman was instructed to accept a demotion or go on leave because she couldn’t do the job of co-director while pregnant.

These are egregious examples; caregiver discrimination is often much subtler, like when a manager gives better assignments to those without known family responsibilities. A supervisor’s actions can still be discriminatory, though well-intentioned. That’s why HR needs to be on the lookout for risky rules and practices.

Just as the #MeToo movement has been a wake-up call for business leaders to do more to address and prevent sexual harassment, the rise in these caregiver cases—and a high success rate for the plaintiffs—should “give employers the impetus to investigate their workplaces and address family responsibilities discrimination before it damages their bottom line and before they face lawsuits,” says attorney Cynthia Thomas Calvert, a lawyer and HR consultant in Maryland and an expert in this area of the law.

Is That Legal?

Most working people will tend to a family member’s health at some point during their careers. If HR and supervisors aren’t careful about how they manage those employees, the result can be costly litigation, low morale and bad press, among other problems.

Employees with family responsibilities are not explicitly covered under federal anti-discrimination laws. But some cities and states have enacted legislation that makes caregivers a protected class. These are Alaska, Minnesota, New York state, New York City, New Jersey and Washington, D.C. Moreover, employers with policies and practices that show or seem to show bias against caregivers, or bias against employees who an employer presumes will have the role of caregiver in the future, may still violate anti-discrimination laws.

“Many HR professionals do not know what family responsibilities discrimination is, or they have trouble spotting it, so they are blindsided when they get sued,” Calvert says.

[SHRM members-only resource: Drafting a Parental Leave Policy that Won't Get You Sued]

Company leaders who are on the receiving end of caregiver discrimination lawsuits are typically accused of violating major civil rights statutes and other laws, including Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Americans with Disabilities Act Amendments Act, the Pregnancy Discrimination Act, the Equal Pay Act, the Family and Medical Leave Act, or the Employee Retirement Income Security Act.

Several risky, and perhaps too-common, practices could violate federal statutes, including:

- Treating women without caregiving responsibilities more favorably than those who have them.

- Asking female applicants and employees, but not men, about their child care responsibilities.

- Retaliating against employees for seeking leave under the federal Family and Medical Leave Act.

- Providing reasonable accommodations for other temporary medical conditions but not for pregnancy.

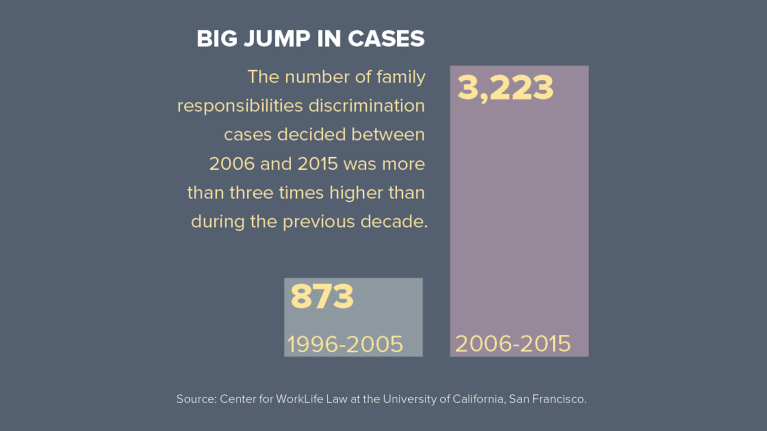

Despite efforts by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) to convince HR and other business leaders to provide better training to managers and take other steps to reduce risk, the number of family responsibilities discrimination cases decided between 2006 and 2015 was more than three times higher than during the previous decade (1996-2005): 3,223 cases compared to 873, according to a study Calvert conducted for the Center for WorkLife Law at the University of California, San Francisco.

Workers have a good track record of winning these cases, too. More than two-thirds of the lawsuits that went to trial were decided in their favor—a far higher success rate than other employment discrimination cases. In the decade ending in 2015, employers paid about a half-billion dollars in verdicts and settlements for these claims.

The Risk of Stereotypes

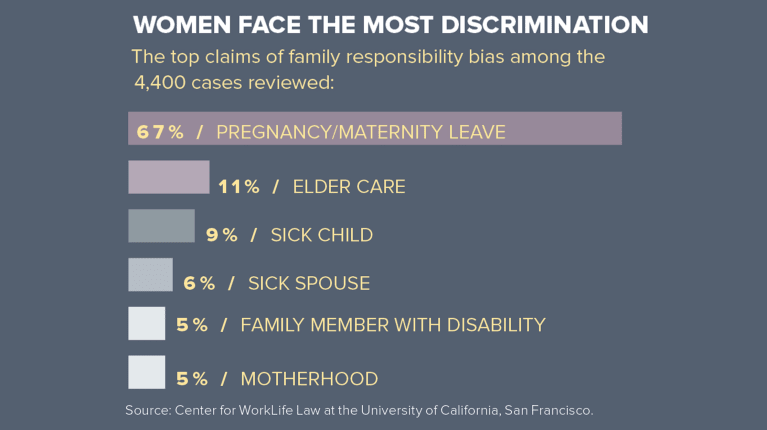

Despite shifting gender roles at home and work, women remain the primary caregivers in most families. So it’s not surprising that the clear majority of employees alleging bias in this area are women.

Among the 4,400 cases Calvert reviewed for her study, almost 7 in 10 were related to pregnancy and maternity leave. A common theme is the assumption by business owners, supervisors and others, in violation of Title VII, that female workers cannot do their jobs if they are pregnant or parenting. In 2017, a federal judge in New Jersey ordered a debt collection firm to pay $118,483 after the EEOC sued it for pregnancy discrimination. According to the lawsuit, the company rescinded its offer to promote a female employee after she announced her pregnancy and was told that the owners of the company did not think that a pregnant woman could handle the stress or long hours of a management position.

The Americans with Disabilities Act makes it illegal to treat workers differently because of their relationship or association with someone who is disabled. In 2016, an Albuquerque doctor’s office agreed to pay $165,000 to settle an EEOC suit involving Melissa Yalch, a temporary staffing agency placement it had promised to hire as a full-time employee but then let go after learning Yalch had a child with disabilities. Her supervisor told her by text, “We have no room here for a disability, and I will not accommodate.”

Claims of elder care discrimination make up more than one of every 10 cases Calvert studied. They are likely to be one of the fastest-growing types of family responsibilities discrimination cases as the U.S. population ages, according to the Center for WorkLife Law.

Allegations by male caregivers are also on the rise. In a high-profile lawsuit filed last year, the EEOC accused cosmetics manufacturer Estée Lauder of illegally discriminating against male employees by offering new fathers only two weeks’ paid leave for child bonding while offering new mothers six weeks. The parties settled the dispute earlier this year without disclosing the terms.

Two Common Legal Theories

There are two common types of caregiver discrimination claims: disparate treatment and disparate impact.

Disparate treatment. These cases stem from employers having a policy or practice under which employees are not treated the same because of a legally protected trait, such as gender or pregnancy. In many instances, the differential treatment is based on stereotypical assumptions about what the worker can or cannot do.

For example, if you avoid hiring women with young children because they tend to need time off for their kids, but don’t have the same concern about male employees, you may be violating Title VII, which prohibits employers from making gender-based assumptions.

Similarly, a supervisor who denies a pregnant employee a promotion could be running afoul of Title VII’s bar on basing an adverse employment decision on stereotypical assumptions about pregnancy.

Keep in mind that it doesn’t matter whether a manager is acting with a hostile intention or a genuine belief that he or she has the employee’s best interests in mind. While women are entitled to specific leave for pregnancy and childbirth that men are not, a manager who grants a mother time off to care for an infant but denies a father’s similar request is likely breaking the law.

Disparate impact. Given the legal risks of an adverse treatment claim, it might seem safest to treat all workers exactly the same. But this can also land you in hot water. Policies and practices that don’t intentionally single out members of a protected class but nonetheless affect those individuals more than other groups are the basis of so-called disparate impact cases.

For example, mandatory overtime could have a disparate impact on women because they are more likely to have caregiving responsibilities that limit the amount of time they can work. Ditto for strict policies that limit flexible schedules.

Requiring employees to stand during their shift might disproportionately affect women who are pregnant or recovering from childbirth, as could limiting the number of breaks workers can take.

Of course, not all those who are accused of disparate impact have done anything wrong. Facing a charge, you can defend yourself by showing that the claim is bogus or proving that the policy or practice that leads to the disparate impact claim is required for the job or business.

5 Tips for Avoiding a Caregiver ComplaintMost employers are not legally required to provide paid leave or other benefits to help caregivers. But be careful not to make decisions that can violate civil rights laws. Here are some tips for avoiding a lawsuit from Tom Spiggle, an employment attorney in Arlington, Va., who has represented workers in family responsibilities lawsuits. Had some employers taken this advice, he says, they never would have had to meet him in court. 1. Work with legal counsel to develop, communicate and enforce a strong equal employment opportunity policy that clearly addresses the types of conduct that might constitute caregiver discrimination. “When there is no policy or procedure, there is risk. If you just leave things up to line managers, there’s a lot of opportunity for screw-ups,” Spiggle says. 2. Train managers on gender stereotyping, which can violate Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and other laws and is a key component of many caregiver lawsuits. An example of this is “when a manager applies a double standard, such as denying leave to a man who needs time off to take care of a child because he has a wife,” he says. 3. Emphasize the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) during training. Given the complexity of the law—and the risk of litigation—make sure managers know they must talk to HR before answering any employee questions or making any decisions surrounding a subordinate’s FMLA leave. 4. Consider hiring a consultant who is an expert on unconscious bias to train all workers. 5. Avoid paternalistic policies regarding work and time off. Managers aren’t in a position to determine what a pregnant employee can and cannot do; doing so may violate the Pregnancy Discrimination Act, Title VII or other laws. |

Taking Care of Caregivers

A small but growing number of companies are recognizing and responding to their workers’ needs by offering new benefits for caregivers. It’s not so much fear of litigation that’s behind these programs but an interest in boosting morale and loyalty.

Deloitte uses an expanded definition of family to allow workers to take up to 16 weeks’ paid leave to provide support to parents, children and spouses, as well as to siblings and domestic partners. Employees can use the time all at once or in increments.

The company’s caregiver benefits are equally available to men and women and geared to accommodate them at every stage of life, says Jennifer Fisher, Deloitte’s national manager of wellness. Workers can use the time before they exhaust other paid leave, so they still have days in the bank if they get sick themselves or want to take a vacation.

“We know that caregiving takes all different forms,” Fisher says. “Our culture is to be inclusive and supportive of people in time of need.”

Washington, D.C.-based mortgage giant Fannie Mae has offered numerous benefits for decades to new parents, including fully paid maternity, paternity and adoption leave, according to Michelle Stone, the company’s work/life benefits manager. But as its workforce aged and employees began voicing concerns about their parents’ health, Stone’s team hired a full-time professional elder care consultant to provide guidance and support. The team also started offering partial reimbursement to workers who needed emergency backup support for either children or adult dependents.

AARP and Minneapolis-based insurer Allianz Life also began offering paid leave to caregivers in 2016. “When life happens, we ask what can we do,” says Jenny Guldseth, vice president for performance, compensation and benefits at Allianz. “We want to know how can we support our people.”

Ava Sloane’s mother passed away in July 2017. She says she’s so grateful for the time Deloitte gave her to be with her mom toward the end of her life. What better support could any organization provide?

Rita Zeidner is a freelance writer in Falls Church, Va.

Photograph of Ava Sloane by Aaron Bristol