Michael Fazen survived three years in combat, but he says nothing was more daunting than searching for a civilian job after leaving the military last year.

“When an IED [improvised explosive device] goes off a couple of hundred meters away, it is scary as hell,” explains Fazen, a retired colonel who spent 26 years in the U.S. Army. “But I had sustained trouble getting to sleep at night, thinking if I don’t do well on an interview, I might not get a job and be able to put food on the table.”

He never had that feeling when he was in the military. He had never looked for job before.

Despite his worries, Fazen was quickly hired last year as a senior program manager at CACI International Inc., an Arlington, Va.-based company specializing in national security technology.

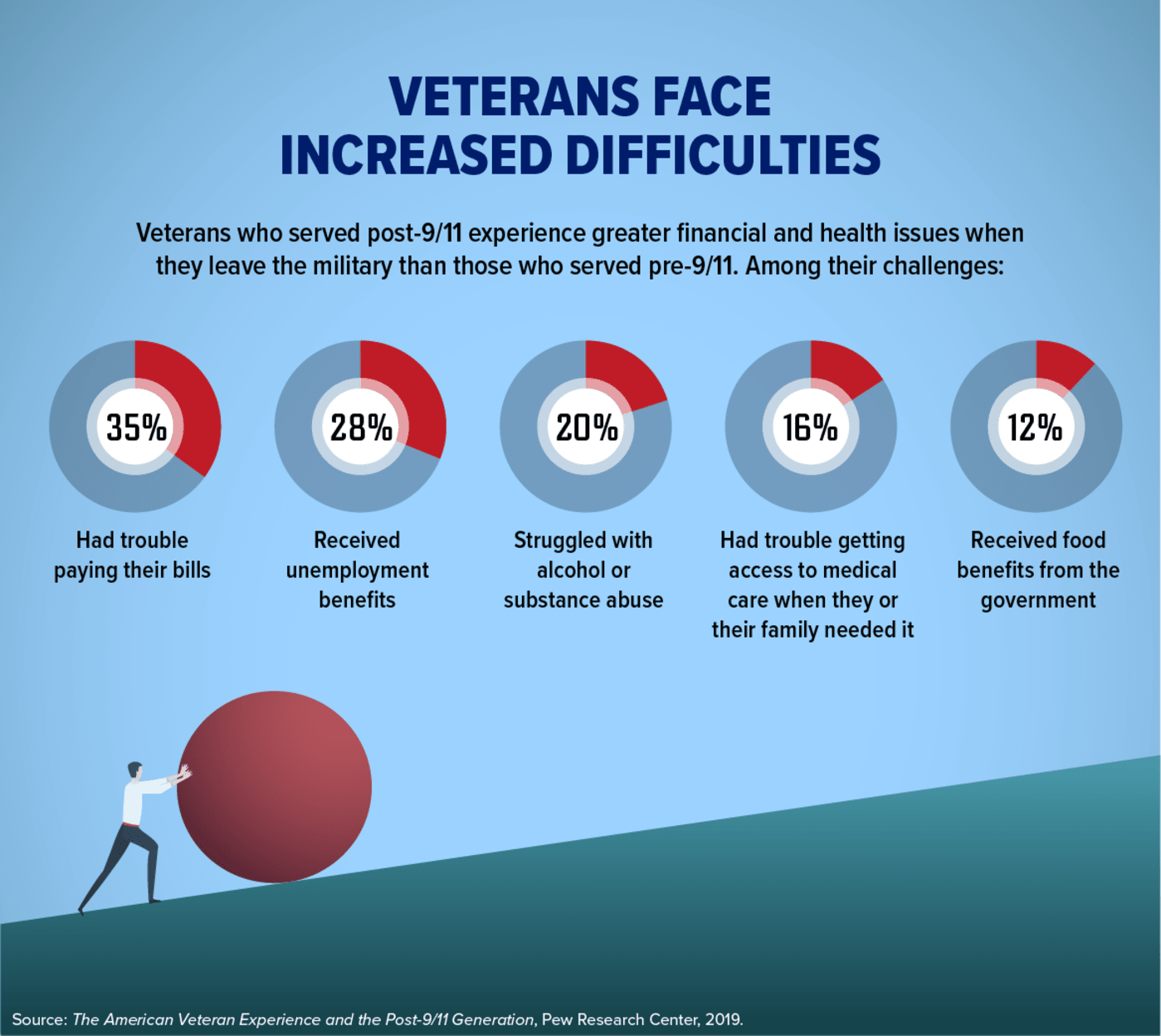

Like Fazen, many veterans agonize about finding post-service employment. They worry about whether their skills are transferable. They’re concerned about adapting to a new culture after serving in a unique institution that’s a largely transparent, hierarchical organization with a well-defined purpose and strict rules.

In recent years, however, the U.S. Department of Defense, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), nonprofits and private companies have worked to provide a smoother transition for those leaving the military.

The VA recently created a pilot program called the Veteran Employment Through Technology Education Courses to help veterans earn certificates in job-ready skills without earning a four-year degree. The VA pays the tuition at approved providers.

Meanwhile, the Defense Department now requires service members to participate in programs designed to ease their transition out of the military, and they must start at least a year before their scheduled departure date. Six years ago, the Defense Department launched the SkillBridge program, which allows active-duty military to attend specialized job-training classes or participate in internships or apprenticeships during the months immediately prior to their transition. The program is especially popular with companies because the military pays the service members’ salaries while the firms get labor and a chance to test out potential employees.

“The VA and Defense Department are really addressing transition, and that’s a great boon for us,” says Laura Schmiegel, head of military and veteran affairs at consultancy Booz Allen Hamilton, based in McLean, Va. Without the transition programs, “veterans can feel there is a mismatch between their skills and the jobs they take.”

Booz Allen Hamilton generates about 47 percent of its revenues from the military, and veterans make up 29 percent of its 27,400 employees. These military transition programs help provide potential employees who understand the military mission and have the critical skills that companies need, Schmiegel says.

Programs That Work

The efforts also benefit the military. With an all-volunteer force, providing current service members a positive transition experience “means they go back into the community and act as ambassadors” for the military, says Michael Bianchi, senior director for education and career training at Syracuse University’s Institute for Veterans and Military Families, which provides research and education.

In the first year, more than 1,500 individuals participated in the new VA tech program. So far, 30,000 service members have participated in the SkillBridge initiative over its six years, according to Boris Kun, director of credentialing and SkillBridge programs at the Defense Department.

This year, 12,000 service members joined SkillBridge, more than double the number in 2018. There are now 425 programs involving 4,500 employers, up from 160 programs at 600 employers a year ago. That’s a result of putting more effort into promoting the program, Kun says.

Some want even greater marketing efforts. In September, U.S. Rep. Elise Stefanik, R-N.Y., wrote a letter to Defense Department officials requesting that it expand the program and advertise it better so more veterans can take advantage of it. About 200,000 service members leave the military each year.

Kleinfelder Inc., a San Diego-based professional services company specializing in construction and engineering, brought on its first intern through the SkillBridge program in 2018. Laura Hartman, SHRM-SCP, senior HR manager, says she learned about the program from her daughter, a Defense Department employee, after complaining that she couldn’t find qualified employees for Kleinfelder’s construction materials testing group.

The company has brought on a total of 10 interns in different departments, including HR and IT. So far, six were offered jobs, and three accepted, Hartman says.

“We’ve been getting good people,” she says. “They want to learn, and they’re interested and engaged.”

However, she says, 34 people expressed interest in internships, but many of their superiors declined to allow them to participate. Commander approval is required. One intern was called back to base full time and couldn’t complete the program. Kun says that it isn’t always possible to let members leave early.

“Mission trumps everything,” Kun says.

The idea for SkillBridge originated in the Great Recession when jobs were scarce, and the military wanted to help boost those leaving the ranks. During the current recession, veterans’ unemployment rates have been lower than for the rest of the population. In September, the unemployment rate for veterans was 6.8 percent compared with the overall rate of 7.8, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Myths and Misconceptions

Veterans still face negative stereotypes when they look for civilian employment, veteran advocates say. There’s a perception among some that veterans are limited to taking orders and lack critical thinking skills to flourish in less structured environments. Also, the news media’s focus on military and veteran suicides could lead employers to believe that all veterans are plagued by post-traumatic stress or other mental health problems.

The misconceptions aren’t surprising. Only about 1 percent of the population has served in the military, leaving the vast majority of Americans with no real connection to the institution. Their impressions come primarily from TV and movies.

“There is very little awareness of what military culture is,” says Margarita Devlin, principal deputy undersecretary for benefits at the VA. “They need to make decisions on the fly, be adaptable. The team approach is stronger than anything in the private sector.”

The SHRM Foundation offers free educational materials for HR professionals, hiring managers and front-line supervisors to help bridge the gap in hiring veterans. It offers a digital toolkit, guidebook and a certificate program for HR professionals that explains the benefits of hiring veterans and how to attract and retain them.

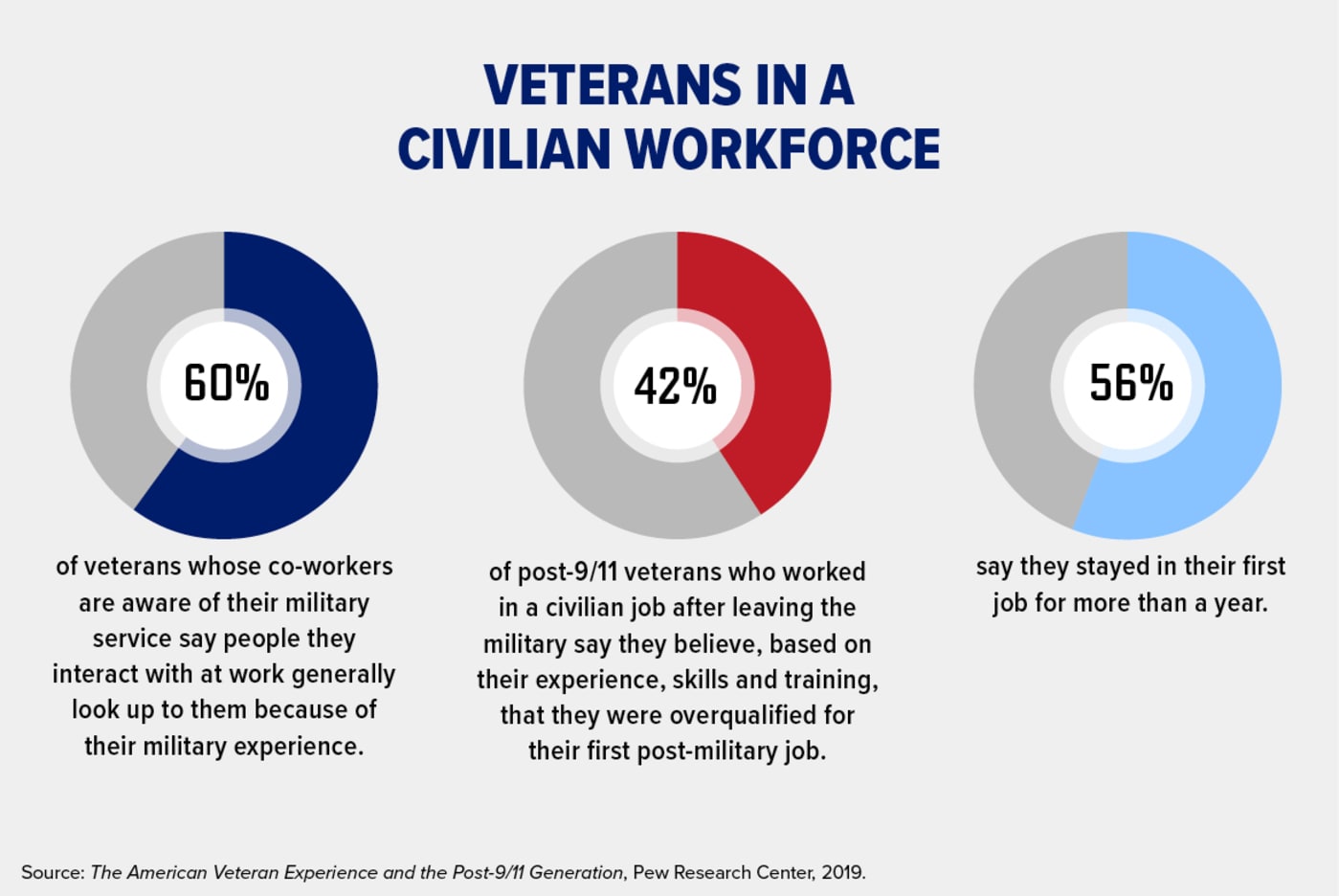

Employers that have hired veterans describe them as hardworking, loyal team players and detail-oriented individuals. They’re able to handle stress and think on their feet. The military’s diversity gives veterans real-life experience working with people of different backgrounds, which is especially valuable as companies increasingly focus on ending racism in their ranks.

Great Expectations

Misunderstandings cut both ways, with some veterans having unrealistic notions of civilian life. They can be shocked by the taxes they have to pay and how much of their salaries can be eaten up by clothes, food and housing costs. Those who commanded troops in battle don’t understand why their experience operating in such an intense, hostile environment doesn’t earn them senior titles with compensation to match

“The military is a world-class training organization that can take anybody and make them efficient at something, but it creates false expectations,” says Jeremy Foshee, an Army veteran who is the military recruiting team leader at Atlanta-based Southern Co., a provider of gas and electricity. “Veterans think ‘If I can do this in the military, then I can just set up here as a VP and be successful.’ I have to explain to 25-year-olds why they aren’t making $125,000 a year.”

The transition isn’t always challenging. James Hannick became a general plant operator at Southern Co. in the spring through the SkillBridge program after spending 20 years in the U.S. Navy as a nuclear electrician.

“There are a lot of similarities between the Navy’s power plants and power plants on the commercial side,” says Hannick, who formerly spent two to three months at a time on a submarine. “To be honest, this is a lot less stressful.”

Hannick says he wanted to work at Southern Co. because of its reputation as a veteran-friendly company. There are certain sectors, such as utilities, defense contractors, and construction and engineering companies, that have long histories of valuing military experience. That list has expanded over the years as the military has become as reliant on technology as other industries. Seattle-based Starbucks and Amazon, for example, earn praise for their efforts to hire veterans.

Amazon hired Joel Dillon in 2017 to work on cloud computing projects after he retired from a 20-year career in the U.S. Army.

“I have to give credit to Amazon. I didn’t know anything about cloud computing,” Dillon says. “They valued my leadership and experience and said they would teach me the tech stuff.”

Dillon acknowledges that his transition from a military to a civilian workplace required an adjustment. In meetings, he was initially confused because he didn’t know everyone’s name and position. Names and ranks are emblazoned on military uniforms. Dillon says he eventually got used to that—and to picking out his own clothes. A U.S. Military Academy at West Point graduate, Dillon had been wearing a uniform since college.

A little over a year ago, he accepted a position as vice president of digital battlefield solutions at Booz Allen Hamilton, which was founded by a veteran. One-third of its 27,400 employees are either veterans, military spouses or members of the National Guard or Reserve or some combination of those.

“It was nice to get that break from the military,” Dillon says. “Twenty years of experience is a big deal. Booz Allen is just a natural fit.”

Improving Retention

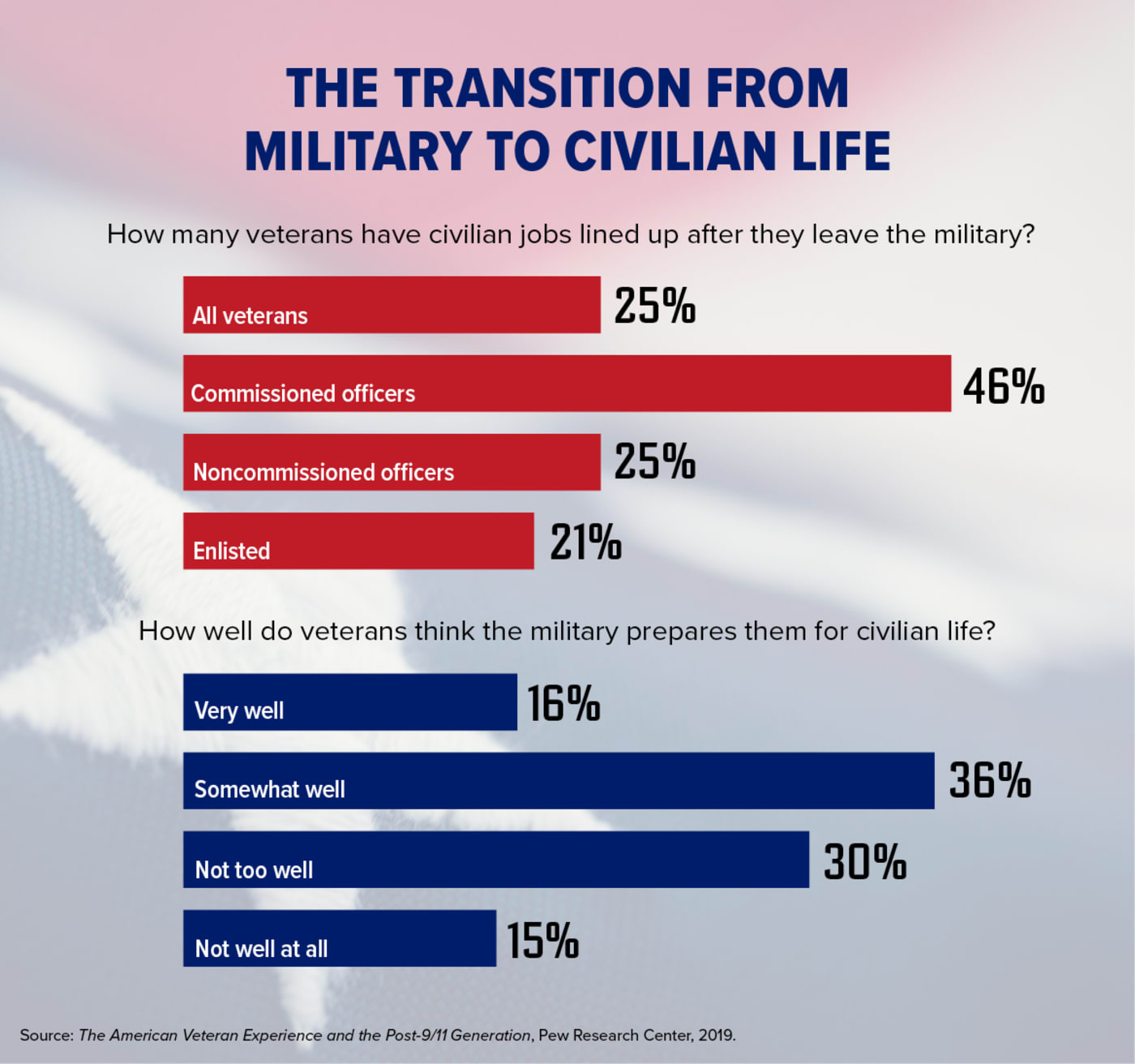

It’s not uncommon for recent veterans to stay at their first post-military job for only a year or so as they adapt to civilian life. Just like many recent college graduates, they’re exploring their options and may take the first job offered just for the paycheck.

Last year, CACI started an inclusion program to increase retention of veterans. Gary Patton, CACI’s vice president of veteran outreach, sends every former service member a personal letter when they’re hired. The letter includes an invitation to join the company’s employee resource group for former military and to participate in its mentor programming. Employee resource groups consist of employees with common backgrounds who join together to support each other and the company. Veterans groups are common even for organizations that don’t have strong connections to the armed services.

However, companies that, like Booz Allen Hamilton and CACI, have strong ties to the services have a much wider variety of offerings, such as efforts to help military spouses and reservists. Roughly two years ago, CACI created a video about suicide and prevention for its employees with the help of a veterans organization.

“As a combat veteran, I’m very sensitive to such issues,” Patton says.

He also understands that maneuvering through a corporate culture can be tricky for those who were accustomed to having the requirements for jobs and promotions clearly stated. The mentoring programming is a personalized way to help veterans acclimate, and it’s open to veterans at all levels as they navigate their way through the company.

With so many federal contractors vying for employees with military experience, Patton wants to ensure CACI retains the veterans currently on staff.

“We know our people are getting contacted all the time” for jobs, he says.

Programs Help Military Spouses Find Jobs

By Theresa Agovino

Laura Schmiegel graduated from the University of Michigan's Law School and passed the bar exam in four different states within six years. Yet she still couldn't get a job. Why?

Her then-husband was in the U.S. Army, and employers are notoriously reluctant to hire military spouses because their families move an average of once every three years.

Recruiters would look at her address and know she was a military spouse.

"I remember the reticence on their faces," recalls Schmiegel, head of military and veteran affairs at Booz Allen Hamilton.

The unemployment rate for military spouses has remained at 24 percent for about a decade, says Meredith Lozar, director of the military spouse program for Hiring Our Heroes, a U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation initiative.

Underemployment among military spouses is between 33 percent and 77 percent, Lozar adds. A military spouse will lose an average of $190,000 in earnings over 20 years, according to a 2018 study by the White House Council of Economic Advisers.

The high unemployment and underemployment are the focus of greater concern within the military community because increasingly families need two incomes to survive and without them, more individuals may be forced to leave the armed services, experts say. And the situation is worsening: The unemployment rate for military spouses is expected to increase to 32 percent because of the COVID-19 pandemic, Lozar says.

Still, as more employers realize that remote work is possible, they may be more inclined to allow military spouses to retain their jobs even when the service member's position dictates a move.

Military spouses are more likely to stay in their jobs to enjoy some stability in lives that often involve vast amounts of change. Lozar adds that about 40 percent of them have bachelor's degrees.

"They are incredible loyal," she says. "Our lifestyle has made us incredibly flexible. We know how to dive right in."

Companies with strong military ties like Booz Allen Hamilton have long made efforts to hire military spouses. But others are following. Seattle-based Amazon recently launched a website to make it easier for its military spouses whose jobs can't be done remotely to find other employment within the company. They can enter their moving timeline, title, salary and job duties to find comparable positions.

"They can continue their professional development within the company," says Beth Conlin, Amazon's senior program manager for its military spouse programs, and the wife of a U.S. Army member.

Conlin has also been reaching out to the numerous military-focused nonprofits to promote training programs the company has developed for military spouses. The first involved training for customer service roles. It will be expanding that next year to train people for two different tech roles as well as other administrative roles. The software training will be remote, though Amazon has set up an in-person Military Spouse Academy to prepare individuals for the administrative positions. Conlin says the focus on military spouses gives Amazon entry into an untapped, diverse talent pool for jobs where applicants can be lacking.

"We are targeting them for good reason," she says.

Theresa Agovino is the workplace editor at the Society for Human Resource Management.

Explore Further

SHRM provides advice and resources to help employers hire and retain veterans.

Employers Share Veteran Hiring, Retention Strategies

To help veterans succeed, companies must shift from a veteran-friendly approach to being veteran-ready, said Chris Cortez, vice president of military affairs for Microsoft, at SHRM’s INCLUSION 2020 virtual conference.

Viewpoint: Identifying Veteran Employees to Create a Military-Ready Work Environment

To measure both the effectiveness of your initiatives to hire veterans and the impact veterans make within your organization, gather metrics on which employees are veterans and where they work.

Employing Veterans Digital Toolkit

Proactive employment practices designed to attract, hire and retain veterans can mitigate challenges faced by employers and veterans. This free toolkit provides resources to help HR professionals lead efforts to integrate veterans into their workforce.

The Recruitment, Hiring, Retention & Engagement of Military Veterans

This free SHRM Foundation guidebook will help employers better understand the value veterans bring to their workplace and how to engage and integrate veterans within their organizations.

HR Q&As: Can an Employer Advertise or State a Hiring Preference for a Specific Protected Class Such as Veterans?

Federal and state tax credits are often available for employers that hire veterans, and the federal government, as well as other state and local agencies, explicitly state a hiring preference for veterans.