Bridging the Talent Gap

Where have all the workers gone? A series of workforce disruptions and demographic trends have led to historically tight labor markets. SHRM economists highlight the fundamental changes that can help ease the problem in 2025 and beyond.

Labor shortages have received an enormous amount of attention in recent years and—although conditions have shown clear signs of improvement in recent months—there are many reasons to believe this spotlight will endure for the foreseeable future. After all, competition for labor remains fierce, and the need to attract and retain talent will always take center stage for HR leaders. Furthermore, ongoing demographic changes, uncertainty surrounding immigration policies, and emerging innovations in the field of artificial intelligence have fueled intense speculation and uncertainty about the future of labor. For all these reasons, we expect this issue will continue to dominate HR discussions in 2025 and beyond.

Quantifying the Current Labor Shortage

The U.S. has clearly been suffering a labor shortage for years, but what is the best way to identify its presence and severity? Although several metrics are tracked for this purpose, one especially intuitive indicator is the ratio of unemployed people to job openings (a value we will refer to as the unemployed per job openings ratio, or UJOR).

In any given month, this ratio is calculated as the size of the unemployed population divided by the number of active job openings as of the last business day of the month. In this ratio, the unemployed population captures the supply of people who could plausibly fill an open position without vacating another, whereas the number of job openings reflects unmet demand for labor.

Here’s how to read the unemployed per job openings ratio:

- Surplus. At least in principle, a labor surplus exists when this ratio exceeds 1.0, because every active job opening could theoretically be filled by a member of the unemployed population in this scenario. In practice, however, other labor market frictions (e.g., skills mismatches) often prevent job openings from being filled even when the UJOR is above 1.0.

- Shortage. In contrast, a labor shortage exists when the ratio falls below 1.0, because—even if it were possible to match every unemployed person to an active opening—there would still be unfilled job openings at the end of that matching process.

Historically, the UJOR has always been above 1.0. In fact, between December 2000 and February 2018, the number of unemployed people typically exceeded the number of active job openings by millions. However, beginning in March 2018, the UJOR fell below 1.0 and remained there until March 2020. After a brief labor surplus in the initial phase of the pandemic, the UJOR dropped below 1.0 again in May 2021 and has remained there ever since. The takeaway from this historical trend: Although the pandemic clearly made the labor shortage worse, workers were already in short supply prior to its onset.

Since hitting its low point in 2022, the labor shortage has gradually improved, mostly because the number of job openings fell steadily from an all-time high of 12.2 million openings in March 2022 to about 8 million in August 2024. However, in 2024, growing unemployment has driven down the UJOR. In fact, between January and August of this year, the unemployed population has risen by roughly 1 million people.

As pervasive as the labor shortage has been in recent years, the gap between job openings and unemployed people has narrowed considerably in 2024. As of August 2024, there were roughly 925,000 more job openings than there were unemployed people, down from about 2.6 million in January. Should this trend continue, employers will face comparatively favorable (albeit still challenging) labor market conditions in 2025.

The Role of Demographic Change

The current labor shortage cannot be explained by any single cause. For example, the pandemic alone introduced several contributing factors, including a decline in labor force participation among older adults. Even so, one of the most fundamental factors predates the pandemic by decades: Demographic change is reshaping the country’s age distribution in such a way that working-age adults represent an increasingly small part of the population.

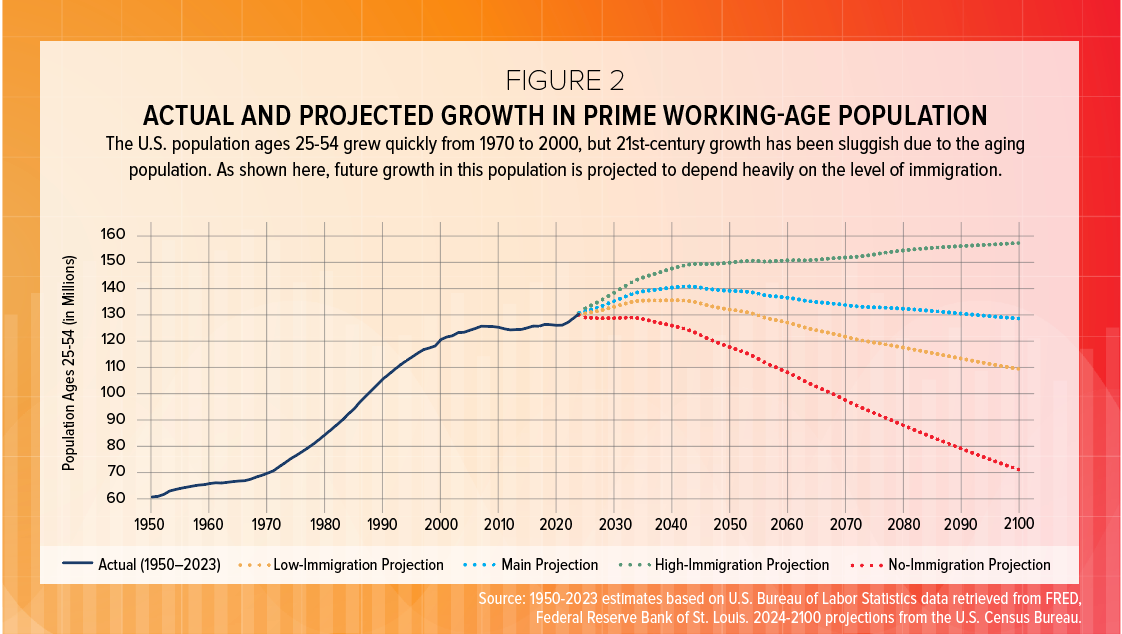

As shown in Figure 2, the population of “prime working-age” U.S. residents (people ages 25-54) grew by more than 50 million people from 1970 to 2000. But that population added only about 8 million people between 2000 and 2023.

During the same 2000-2023 period, the percentage of U.S. residents ages 25-54 fell from nearly 43% of the total population to just over 38%. Prime working-age adults have historically accounted for a large majority of the U.S. labor force. As such, this group’s slow growth during the 21st century has significantly constrained overall labor supply growth in the U.S.

The rapidly growing quantity of prime working-age adults from 1970 to 2000 can largely be attributed to the Baby Boomer generation, whose members began reaching prime working age around 1970. For decades after, the prime working-age population grew at a strong rate. However, by 2000, Baby Boomers began turning 55 and growth slowed substantially.

The central challenge with trends described here is that, due to rapidly declining fertility rates, the population of young people aging into prime working age every year is declining steadily over time. In fact, this population will soon be insufficient to replace older people exiting prime working age. As a result, population projections from the U.S. Census suggest that future growth in the prime working age population will be largely dependent on immigration.

Given that population aging is a long-running global phenomenon, we have every reason to believe that this demographic transition will continue to constrain labor supply growth for the foreseeable future. As such, in the absence of monumental demographic, behavioral, or technological change, it is reasonable to assume that labor shortages will be a common challenge going forward.

That said, it is important to emphasize that employers should not necessarily expect a constant state of labor scarcity going forward. In fact, the U.S. labor market has cooled significantly in 2024, which has mitigated or even eliminated the labor shortage in some sectors. Based on these recent developments, many employers should enjoy comparatively favorable labor market conditions in 2025, though the overall labor market will likely remain tight by historical standards.

Solutions for 2025 and Beyond

Although the current labor shortage may seem like an intractable problem, clear and plausible pathways exist that could help ease the current labor shortage over time.

Immigration reform. Policies aimed at encouraging and facilitating legal immigration to the U.S. may provide the quickest path toward stronger labor force growth, especially in the prime working-age population. In fact, according to U.S. Census population projections (see Figure 2), achieving a high-immigration scenario would allow the prime working-age population to grow by about 30 million people by 2100.

Politically charged issues such as border security and immigration policies will almost certainly make it difficult to pursue this pathway in 2025. However, given the current trends of an aging workforce and low birth rates, immigration may be the most powerful policy lever available for increasing labor supply over a longer time horizon. (Learn more about SHRM’s workplace immigration reform initiatives on page 58.)

Greater participation from older and younger workers. Another necessary part of the solution for the labor shortage is to pursue policies that promote greater labor force participation, especially among those ages 16-24 and older than 55.

Rising labor force participation among older adults—especially those older than 65—has already been a critical boon to labor supply for decades. However, even though older adults have substantially grown their labor force representation with relatively limited intervention from policymakers and employers, several key steps could spark greater participation among the oldest and youngest adult age groups.

For example, investing in reskilling and upskilling programs could be hugely beneficial for older adults, especially those whose existing skills have become dated or obsolete via technical change. Similarly, vocational training programs could help young adults enter the labor force sooner and with more competitive skills. This is an especially prominent issue for males ages 16-24, whose labor force participation has fallen significantly in recent decades, even among those who are not enrolled in education programs.

Technological change. One final development that will fundamentally disrupt the labor market relates to technological change, especially labor-replacing AI tools. A recent Goldman Sachs report estimated that increasingly sophisticated AI tools could expose the equivalent of 300 million full-time jobs to automation globally. The study also said that about two-thirds of U.S. occupations are exposed to some degree of automation via AI.

However, that same report emphasized that exposure to AI-based automation is not the same as labor replacement, and that AI tools will represent a complement to human labor in many contexts. At the moment, there is too much uncertainty in this area to meaningfully predict how AI will alter the current labor shortage. Even so, AI tools are already being deployed to save labor, and any employer wishing to successfully manage a labor shortage in 2025 would benefit from a comprehensive plan that incorporates these tools wherever possible.

Inflation and Interest Rates in 2025

As much attention as the labor shortage received in recent years, inflation has loomed even larger in the minds of policymakers, business leaders, and the public. Where are we headed? Here are three possible scenarios for inflation and interest rates in 2025 and how they could impact employers.

Justin Ladner is the senior labor economist at SHRM and previously served as the senior policy advisor at AARP.

Sydney Ross is an economic researcher at SHRM.